By Yeh Tzu-hao, Lin Shu-zhen, and Chen Mei-yi

Abridged and translated by Wu Hsiao-ting

Photos by Hsiao Yiu-hwa

Tzu Chi volunteers provided material and emotional support for crew members stuck on a ship.

Tzu Chi volunteers went to Taipei Harbor in late September 2021 at the request of Taiwan’s Maritime and Port Bureau to offer help and support to eight crew members on board the ship De Yun. By that time, the eight Burmese and Chinese crew members had been stranded on the cargo vessel for nearly two years. The shipowner had stopped paying the crew their wages in early 2020. Then the pandemic hit, making it difficult for the sailors to return to their home countries.

“We all chose to work at sea because we come from poor families,” said one of the crew, Liu Shu (not his real name), who is from China. “Now we can’t get our pay and we can’t go home. My girlfriend back in my hometown keeps telling me she wants to break up with me….” Pushed over the edge by the strain of being trapped on the ship, he had tried to commit suicide twice.

The others stuck onboard had had a tough time too. Shipmaster Nai Nai Aung (not his real name) is from Myanmar. The pandemic had hit his country hard during the time he was trapped onboard, taking his father’s life. His wife also had to sell their house because with his wages withheld, he hadn’t been able to send any money home in a long time. He was weighed down by worry. His fellow Burmese on the ship had not fared better—their family members had died of COVID or been forced to sell their property to make ends meet too. The crew had repeatedly demanded their back pay from the ship’s owner, but to no avail.

Liu Shu is a marine engineer. “Thinking back on it now,” he said, “we’ve completely wasted the last two years.” He continued and provided the visiting volunteers the backstory, explaining how he had gotten here.

Tzu Chi volunteers started visiting the crew of the ship De Yun in late September 2021 to provide care for them.

In late July 2019, he boarded the ship De Yun, docked in the seas off Zhejiang Province, China, after reaching the vessel via a shuttle boat. The 28-year-old ship was 80 meters (262 feet) long and had a full load displacement of 2,800 tons. Since the ship was old, the working conditions onboard were not so good. The shipowner promised Liu Shu he’d be able to receive his first pay two weeks after he boarded the ship, so he accepted the job without thinking too much about it.

“I should have signed the contract as soon as I got onboard,” Liu recollected, “but the shipowner told me we’d do that after we reached Taiwan.” He had worked as a seafarer for nearly eight years and had never had his wages owed him on a long-term basis. Trusting the shipowner, he didn’t voice any objections.

“When we first arrived,” he continued, “we docked in the waters off northern Taiwan. But two typhoons hit during that time, so we ended up moving to other waters to avoid the storms.” He remembered that they spent the Mid-Autumn Festival that year on the sea (Mid-Autumn Festival is a major Chinese holiday). Only afterwards did they enter Taipei Harbor and moor there. The original shipmaster was transferred off the ship at this point and replaced by Nai Nai Aung. Some Burmese men joined the ship as crew at that time too.

The time the ship lay at anchor in Taipei Harbor stretched from days to weeks to months. People who have some basic maritime knowledge know that it is unusual for a cargo ship that is in operation to stay docked for a long time. But because the crew of the De Yun were still receiving their wages at the time, they didn’t give much thought to the shipowner’s abnormal behavior. It wasn’t until January 2020, when their wages stopped, that they became worried.

The crew’s situation seemed to be a case of seafarer abandonment. Taiwan’s Maritime and Port Bureau began closely monitoring the ship’s situation.

Even though concerned authorities in Taiwan had been alerted to the problem, there wasn’t much they could do about it. The De Yun was a “flag of convenience” ship, one that flies the flag of a country other than the country of ownership. The vessel was flying the flag of Belize but the company was registered in the British Virgin Islands. The nationality of her owner was Chinese and the eight crew members on board the ship were either Chinese or Burmese. Since no Taiwanese were involved, it was difficult for Taiwan’s government to intervene in the labor dispute on the De Yun.

Chen Li-wen (right) was the main contact person for the mission of providing support for the ship’s crew. She and the other female volunteers responsible for the job were nicknamed “Mama Tzu Chi” by the crew.

Under normal circumstances, the crew on board could have applied to enter Taiwan, but these were not normal circumstances. After the coronavirus pandemic started, Taiwan banned the entry of all foreign nationals. The crew had no choice but to stay onboard.

The ship’s docking fees were in excess of 20,000 New Taiwan dollars (US$660) a day. The shipowner had been paying those—in fact, he had paid more than 10 million New Taiwan dollars (US$333,000) over two years—but yet continued to withhold the salaries he owed the crew. The crew were incensed. That was why they continued to stay onboard to negotiate with the owner. But even if they wanted to return home, pandemic restrictions had made everything so difficult. In a word, they were stuck.

To prevent the De Yun from continuing to occupy a berth at Taipei Harbor and affect the port’s operation, port authorities were eventually forced to move the ship to the most remote corner of the harbor. They only moved it back to a safer area when a typhoon was bearing down.

Though they had literally entered Taiwan, the crew members had never cleared customs. They were thus forced to confine their daily activities to the ship itself or on the embankment next to the vessel. A shipping agency supplied the vessel every two weeks with fuels, drinking water, and food, but such supplies were limited. Besides, the crew needed more than food and the minimum daily necessities to live. Their clothes were worn out. Their nerves were frayed. They weren’t being paid and they missed home. What they needed more than anything was help.

Their predicament made the news in Taiwan in July 2021. Liu Shu and Nai Nai Aung both spoke up in front of cameras for their own rights and those of their crewmates. After that, the shipowner indicated that he was willing to pay the crew 60 to 80 percent of their outstanding wages. In the end, the Burmese crew received only minimal pay, while Liu Shu and another Chinese national, the ship’s chief engineer, didn’t receive a penny because they hadn’t signed contracts with the shipowner.

To improve sanitation on board the De Yun, Tzu Chi volunteers bring cleaning products and bleach to the crew and teach them how to use the bleach to disinfect their environment. Courtesy of Chen Li-wen

Meeting every Wednesday

Since officials at the Maritime and Port Bureau were powerless to do much about the labor dispute, they turned to the private sector to ask for help for the crew. One official said after boarding the De Yun to check the conditions on board: “The clothes the crew wore were tattered beyond imagination. When we returned to our office, we immediately rustled up clothes from our colleagues and delivered them to the crew to wear.” They also began calling upon private charity organizations for assistance.

On September 11, 2021, they submitted an appeal to Tzu Chi, asking if the foundation could pay for the crew’s plane tickets home as well as help with their COVID screening and quarantine expenses. Because the crew hadn’t yet been allowed to leave Taiwan, the foundation decided to provide them with daily necessities and humanitarian care first. On September 26, Tzu Chi social workers in northern Taiwan contacted volunteers in Tamsui and Bali, near Taipei Harbor, and asked them to provide care for the crew.

“I was volunteering at the Bali Recycling Station when I received the request for help from Brother Kang Chun-de (康春德),” recalled volunteer Chen Li-wen (陳麗雯), who had lived for many years in Shanghai, China. She took on the role of contact person for the mission they were given. “Immediately afterwards, the two of us went to Taipei Harbor with five other volunteers: Jiang Qing-wen (蔣慶文), Ye Mei-hui (葉美慧), Qiu Chun-ying (邱春瑩), Wang Guo-min (王國民), and Zhou Ming-hong (周明鴻).”

The team from Tzu Chi, bringing rice, instant rice, noodles, soybean milk powder, and other food, arrived at the ship in the company of port officials and met with the crew on the embankment. The crew were either in their 20s or 30s. The volunteers felt for them when they saw how dispirited they were and yet how full of anger they were about what had happened to them. Volunteer Wang Guo-min, a Burmese of Chinese descent, served as interpreter as the team inquired about the crew’s needs.

After they returned, they picked out suitable autumn and winter clothes at home and at recycling stations and delivered them to the crew. They brought a box of pomelos too—the Mid-Autumn Festival had just passed and the citrus fruit was a popular food during the festival. The crew were overjoyed to see the fruit. Carefully peeling away the skin, they bit into the pulp. They ate sparingly to make the pomelos last longer. “Thank you,” they said to the volunteers. “We haven’t had fruit in a long time.”

Volunteers began visiting the crew every Wednesday. Chen Li-wen formed a core team with two other volunteers, Lai Yun-xin (賴雲新) and Su Jin-guo (蘇金國), another Burmese of Chinese descent. They’d visit the crew every week along with other volunteers. Volunteers Huang Qiu-liang (黃秋良) and Chen Jian-ji (陳建基) prepared a second-hand refrigerator for the crew when they learned that the one on the ship had broken down. This helped solve the food storage problem on the vessel.

The volunteers had noticed before that some of the crew had rashes or other skin problems, but it wasn’t until the team saw pictures of the crew’s untidy and messy living conditions on board that it occurred to them that it might have to do with the unhygienic environment on board. They responded by bringing the crew cleaning detergents and bleach and urging them to tidy up their living quarters. They also asked the crew to photograph their living space when they were done. “When everything became clean and tidy after their cleanup,” said Chen Li-wen, “they were very happy and cheerfully shared the results of their efforts with us.”

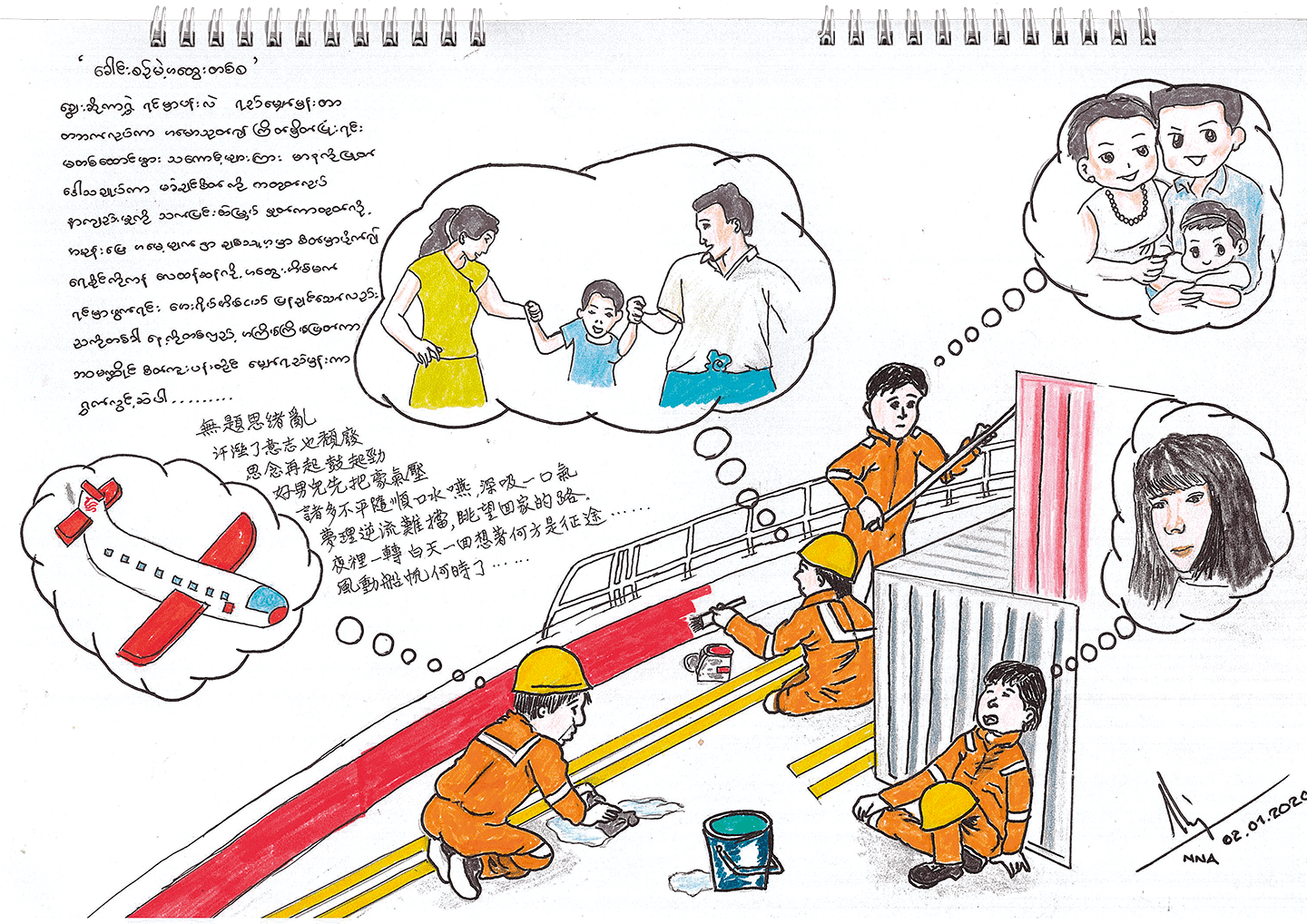

The captain of the De Yun created drawings depicting their lives on board and the crew’s longings for their families in an album given him by Tzu Chi volunteers. On the drawing pictured here, the captain’s Burmese writings were accompanied by a Chinese translation done by a Tzu Chi volunteer.

Lifted by Jing Si aphorisms

Besides material aid, volunteers provided something even more important—emotional care and support.

Henan Province in China was pummeled by severe flooding in July 2021. Liu Shu’s hometown was hit hard. With the help of Tzu Chi, Liu learned that his father and grandmother, after being evacuated by the local government, had safely returned home. Even so, he was still worried about them. To ease his mind, the team responsible for caring for the crew asked for help from their counterparts in China. They first contacted Qiu Yu-fen (邱玉芬), a volunteer in Shanghai, who in turn contacted volunteers in Henan and asked them to visit Liu’s family to check on them. Volunteers in Henan, after completing their relief work for the flood, traveled across half of the province to Liu’s home in Tanghe, in the city of Nanyang, to extend care to his family. They arrived loaded with gifts for the family.

When Liu’s father learned about his son’s situation in Taiwan from the visiting volunteers, he asked them to tell his son that all they cared about was that he was safe and well, and that he would return home in one piece. It didn’t matter that he couldn’t send money home. “Though our family is poor,” the father said, “I believe we’ll pull through any difficulties.”

The volunteers relayed the father’s messages and photos they had taken to volunteer Chen Li-wen, who then forwarded them to Liu Shu. Liu’s eyes brimmed with tears when he saw the messages and pictures. “You Tzu Chi volunteers are really something,” he said. “It’s amazing how you could find my family in such a short time and even personally visit them.”

Chen and other volunteers often shared Dharma Master Cheng Yen’s teachings and video clips of Tzu Chi activities with Liu Shu. They gifted him copies of Tzu Chi Monthly and other publications too. Something Liu heard in one of the videos happened to reflect his experience: “If not driven to the edge by despair, why would one choose to take one’s life?”

It was then Liu tearfully told Chen that he had tried to commit suicide when his girlfriend left him.

“You aren’t afraid even of dying,” Chen said after hearing Liu confess. “What else is there to be afraid of? A lot of opportunities will be waiting for you once you get back to your hometown. Don’t ever do anything foolish again.”

Because the crew were often gloomy and depressed, the volunteer team asked them if they’d like to copy Buddhist sutras to cultivate spiritual merits for themselves and their family and to pray for safety on their way home. Taking their suggestion, Liu copied the Heart Sutra 108 times in three days. Even before he was done, he had memorized the sutra and felt a lot more peaceful.

Chen and the other volunteers also encouraged the crew to copy Jing Si aphorisms, wise sayings by Master Cheng Yen. Volunteer Su Jin-guo translated some of the sayings from Chinese into Burmese so that the Burmese crew could copy them too. He also asked them to share their thoughts about the aphorisms.

“One time they asked me to explain this aphorism: ‘Spiritual cultivation must be carried out in society,’” Su said. “I experienced a mental shock when they asked.” He explained that the Burmese people put a premium on carrying out one’s spiritual practice away from the crowds, up in remote mountains. Master Cheng Yen, on the other hand, stresses the importance of doing one’s spiritual practice among people. Su believed that the aphorism would benefit the Burmese crew and inspire them to think differently. It was like planting a seed in them that might inspire them to walk the Bodhisattva Path and contribute to the greater good of the world.

The team suggested to Liu and the Burmese crew that they also attend online study group sessions organized by volunteers in China and Myanmar. This way they’d be exposed to Buddhist teachings more often even though they were trapped on the ship.

Due to the influence of Tzu Chi, the crew began to interact more frequently with their fellow crewmates from the other country. It was through such interactions that Liu Shu learned that the several young Burmese often slept poorly, and that they’d break down and cry in each other’s arms when they missed their family at night.

The crew had lived through two difficult years. They were angry about being abandoned by the shipowner, frustrated they couldn’t send money home, and anxious their family might worry about them when they learned about their situation. All sorts of emotions seethed within them as they were trapped on the ship. The knots in their hearts, however, gradually unraveled due to the care they were receiving from the Tzu Chi volunteers and the inspiration they were deriving from Buddhist teachings and Jing Si aphorisms. Meeting the volunteers every Wednesday became one of the things they looked forward to the most.

Nay Myat Htun (an alias), one of the Burmese crew, said, “When we were at the lowest point in our lives, when the going got really tough, we received Tzu Chi’s help. We’re really grateful to the volunteers for helping us find peace through the Buddha’s teachings and Jing Si aphorisms and break free from our agitated and troubled minds.”

A cab driver sprays Liu Shu with a disinfectant before taking him to customs, a hospital, and Taoyuan International Airport to run through the necessary procedures before he can leave Taiwan.

Giving back

On December 1, when a cold northeast wind was blasting, the crew gave their warmest best wishes to the Taiwanese society that had extended care to them by donating soap they had made to Tzu Chi for charity sale. They wanted to help the foundation raise money to pay for the COVID vaccines they had donated to Taiwan. The crew had made the soap using materials and tools provided by the volunteer team.

“I made a good wish with every bar of soap I made,” said Shipmaster Nai Nai Aung. “I also made some paper cuttings. I spent nearly two hours creating these cuttings—my eyes were all blurry by the time I was done.” The captain gingerly picked up some of the soap and paper cuttings he had made. The paper cuttings were in the shape of the Chinese character for “blessing.”

As 2021 drew to a close, Liu Shu decided he would not be fettered any more by the shipowner’s dishonest behavior. He decided to go home, reunite with his family, and marry his girlfriend, who had changed her mind about leaving him.

After he submitted his application to leave Taiwan, the Maritime and Port Bureau, the National Immigration Agency, and other government agencies worked together to simplify the procedures so that Liu could return home sooner. The volunteer team was very happy for him. Volunteer Ye Deng-xian (葉燈憲), a commercial airline pilot, gifted Liu a custom-tailored suit and accessories so that Liu could look his best on his wedding day.

“I’m really happy to be getting married,” said Liu. Trying on the suit, he had a picture taken at the helm of the De Yun amidst the cheers of the volunteer team and his fellow crew members. His spiffy look brightened even the old ship, marked by spots of rust and other signs of wear and tear.

Liu was scheduled to leave Taiwan on December 15. He completed his entry and exit procedures that day and took a COVID-19 nucleic acid test. With proof of a negative test result in hand, he arrived at Taoyuan International Airport that afternoon, ready to fly back to China. Volunteers Chen Li-wen, Lai Yun-xin, and Ye Deng-xian had accompanied him through the procedures of the day and then saw him off at the airport.

As soon as Liu checked into a quarantine hotel in Shanghai, he took a video of himself and sent it to the volunteer team. He said in the video: “What had happened to me in the past two years had brought home to me life’s impermanence and unpredictability. None of us knows what will happen to us in the next moment. That’s all the more reason why we must make the most of every day and never squander time away.” He continued: “I’ve arrived back in China loaded with blessings from all of you. I’ll work hard and follow in your footsteps to do good and sow more blessings.”

One day he sent Chen a message telling her his girlfriend had agreed to a vegetarian wedding and even said she’d volunteer in Tzu Chi distributions with him in the future. Chen responded by sending him a thumbs-up sticker.

After Liu returned to China, the other crew members followed the same path and returned to their home country one after the other too. They continued to fight for their rights with the help of Taiwan’s pro bono lawyers, hoping to one day get what was owed them.

Chen and her fellow volunteers were very happy they could give the crew a hand when they were feeling helpless and lost, trapped in a foreign land. They hoped that the care the crew received from them would make an imprint in their hearts and inspire them to generously give to others their love and kindness in the future.

Tzu Chi volunteers Chen Li-wen (second from right), Lai Yun-xin (far right), Ye Deng-xian (third from left), and others pose with Liu Shu (second from left) at Taoyuan Airport before Liu’s departure from Taiwan.