By Chiu Chuan Peinn

Translated by Wu Hsiao-ting

Harvested rice grains (left) become edible rice (right) after hulling and milling, each grain representing farmers’ hard work. Hsiao Yiu-hwa

When Daw Thida Khin visited Myanmar’s rural areas with Tzu Chi volunteers 16 years ago, she was struck by a troubling paradox: farmers could grow rice but couldn’t afford to eat it, instead having to borrow money to buy rice.

Once known as the world’s rice bowl, Myanmar suffered devastating losses in 2008 when Cyclone Nargis flooded the Irrawaddy Delta, the country’s main rice-growing region, with seawater. The entire harvest was wiped out. After the disaster, Daw Thida Khin, an ethnic Chinese woman born in northern Myanmar and the wife of a Taiwanese businessman, joined a team of Tzu Chi volunteers—mostly from Malaysia—to assess the damage in areas around Yangon City.

In northern Myanmar, she explained, farmers generally lived comfortably, whether living in wooden stilt houses or brick homes. Every household had a rice granary to store their harvest, using it gradually while waiting for better market prices. But when she arrived in Yangon, she was surprised to find that farmers’ houses were small and lacked granaries. She couldn’t help but ask, “Don’t you store any rice? What do you eat throughout the year?”

Flooding is common in some regions of Myanmar, leading to unstable harvests. When yields are poor, farmers must borrow money to buy seeds and fertilizers for the next season. While they usually borrow from government sources with lower interest rates, failure to repay forces some to turn to private lenders with higher rates.

As interest accumulates, many farmers become overwhelmed by debt, often having to surrender their harvest to creditors and take on extra work to survive. Some even use their land as collateral, eventually becoming tenant farmers.

“Local farmers told me that many were already in debt before Cyclone Nargis hit,” Daw Thida Khin recalled. “When they harvested, their crops went straight to paying off their debts. I saw many families whose rice containers were completely empty.”

When the land no longer belongs to the farmer, neither does the rice they grow. To eat rice, they must take on additional work to afford it.

Giving them what they need

After Cyclone Nargis, Myanmar experienced several other floods. In the immediate aftermath, Tzu Chi provided aid in the form of food, daily necessities, and school supplies. The foundation then shifted its focus to agricultural support, offering farmers rice seeds, fertilizers, and vegetable seeds for crop rotation to help restore soil nutrients. These efforts aimed not only to alleviate the post-disaster food crisis and increase farmers’ incomes but also to prevent them from leaving their farmland and hometowns in search of work.

U Thein Tun, a rice farmer living in Tha Nat Pin, Thanlyin Township, Yangon Region, had long been repaying debts with his harvest while working extra jobs to support his family. He rented an ox to plow four acres of land, allowing him to harvest ten barrels of rice per acre. Unfortunately, the cost of renting the ox was 20 barrels. During the rainy season, when farming was impossible, he had no choice but to borrow money to buy rice.

In 2010, he received rice and seeds from Tzu Chi and was inspired by the story shared by volunteers of Tzu Chi’s humble beginnings: how a small group of people saved a little money every day to help those in need. Moved by how small but regular contributions can accumulate to benefit many, he started setting aside a handful of rice each day for charity. Despite his poverty, he faithfully continued this practice, even when it meant he had little left for himself. Not only did he save rice in his own rice bank, but he also traveled to other villages to promote the practice, encouraging others to set aside a small portion of their rice each day to help those in need.

In August 2015, Myanmar experienced its worst flooding in 40 years due to continuous heavy rains and Cyclone Komen. More than 200,000 hectares of farmland were submerged. U San Thein, from the village of Shwe Na Gwin in Okkan Township, Yangon Region, was among the 21,000 households that received rice seeds from Tzu Chi in the aftermath. After learning how a handful of rice could help others, he began promoting the concept from household to household, even purchasing containers for others to store their rice. Thanks to his efforts, many villagers in Shwe Na Gwin joined the rice bank initiative. Even residents from neighboring villages began to participate.

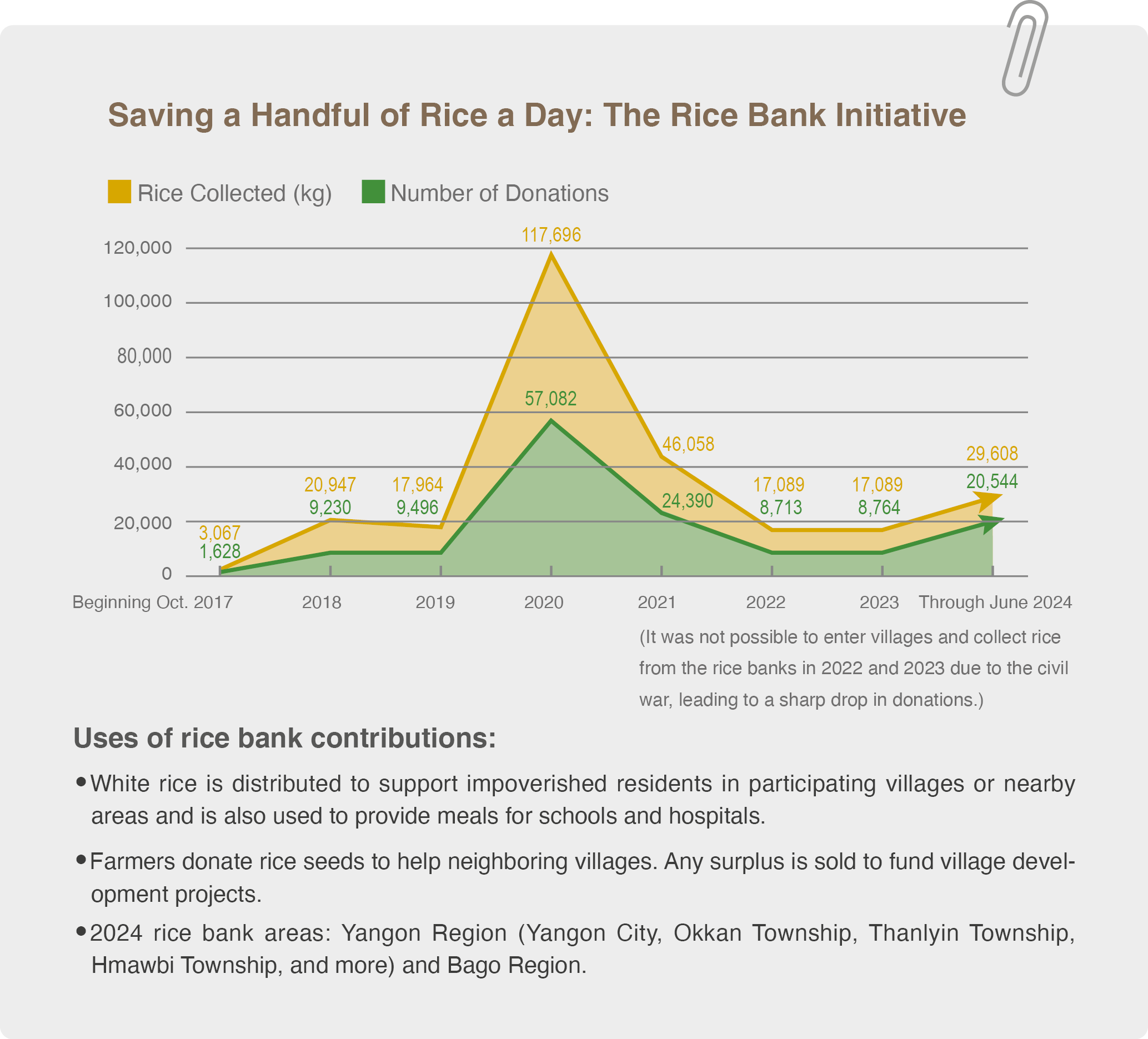

Today, over 200 villages in the Yangon and Bago Regions participate in the rice bank initiative. Families set aside a handful of rice before cooking, contributing without sacrificing their own food security. In 2020, the campaign collected over 117,000 kilograms (257,940 pounds) of rice. Although participation temporarily declined due to the COVID-19 pandemic and political instability, the initiative began to recover in 2024, with nearly 30,000 kilograms of rice donated in the first half of the year. Daw Thida Khin noted, “It’s heartening to see villages once inspired gradually rejoining the effort.”

Shwe Na Gwin, once the poorest village in Okkan Township, has undergone a remarkable transformation. Cement roads, a reinforced concrete bridge, and solar panels now mark the landscape. The new roads allow farmers to transport their crops directly to town, bypassing middlemen. Nearly 90 percent of families have paid off their debts, allowing farmers to regain control of their harvests. Another positive outcome is that 200 villagers now volunteer with Tzu Chi.

Villagers in Myanmar save a handful of rice from their home supplies each day, allowing them to fill a Tzu Chi rice bank with a capacity of 2.6 kilograms in about 20 days. In the photos, villagers happily receive empty rice banks from Tzu Chi, while volunteers regularly visit participating villages to collect donated rice to assist those in need. Photo 1 by Hsiao Yiu-hwa; photo 2 by Kyi Lee Lae Oo

Ongoing challenges

Myanmar has been embroiled in internal conflict for four years and has faced international economic sanctions. While the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic has largely subsided, inflation continues to affect livelihoods, with prices for daily essentials tripling. The supplies Tzu Chi distributes to disaster victims and other vulnerable groups—such as crop seeds and building materials—are all sourced locally, and their costs have inevitably risen due to inflation. For instance, last October, during the rainy season, the Bago Region experienced another severe flood, with floodwaters lingering for 14 days. The rising prices complicated Tzu Chi’s relief efforts, but volunteers pressed on, providing hot meals to survivors. They also launched an agricultural recovery plan, in which fertilizers were supplied to villages in Okkan participating in the rice bank initiative. Though the town of Okkan is outside the Bago Region, it was also affected.

Due to the internal conflict, many towns have been placed under lockdown. Villages under Tzu Chi’s long-term care have also been locked down, with some losing all contact. Have local farmers’ livelihoods thus been severely impacted? Volunteer Daw Thida Khin is pessimistic but still holds on to hope. “We’ve been waiting for our chance to go back in,” she said.

Shwe Na Gwin village was placed under lockdown, but fortunately, it was lifted after a few months. As the flow of resources into the village increased, its situation began to improve. Despite frequent natural disasters and the ongoing conflict, villagers continue to donate a handful of rice each day. Tzu Chi has partnered with the Ministry of Agriculture, Livestock, and Irrigation to improve agriculture in the area. The ministry teaches farming techniques, while Tzu Chi supplies plows and rice harvesters, which villagers can rent at half price. The funds raised from this system provide for road repairs or other development projects in the village. Farmers also donate rice seeds according to their ability to help neighboring villages. Any surplus seeds are sold, with the proceeds further contributing to development projects in the village.

In the past, rice collected from the villages participating in the rice bank initiative was transported to Yangon to support Tzu Chi care recipients. Today, however, the rice is used locally, first to support elderly individuals without family and then households facing financial hardship. By early July 2024, more than 2,200 instances of aid to households had been recorded.

Volunteers also use rice from the rice banks to cook vegetable porridge for underprivileged patients at three hospitals. “The people of Myanmar have a tradition of donating money to hospitals out of goodwill,” said Daw Thida Khin. “We chose three institutions that receive fewer donations as our focus of aid. Generally, those who go to government hospitals are less well-off. The porridge Tzu Chi provides can help ease these patients’ burden.”

Volunteers also provide lunches to students at six schools in Shwe Na Gwin, Thae Pyar, Waw, and other locations. They design menus, share them with teachers, and employ village women in a work-relief program to cook. The meals use rice from rice banks and vegetables grown by local farmers, with any additional ingredients purchased as needed. Daw Thida Khin explained the reason behind the initiative: “The pandemic and political instability in recent years have led to rising unemployment, leaving many families with unstable incomes. As a result, many children could no longer bring lunch to school.” With school hours running from 9 a.m. to 3 or 4 p.m., these meals help children stave off hunger throughout the day.

“In some villages, safety concerns prevent volunteers from entering, so we ask teachers to help,” Daw Thida Khin added. “Our volunteers call to ask, ‘What dishes did you cook today?’ We must ensure the meals are nutritious.” From June 2023 to February 2024, more than 38,000 nutritious lunches were provided to students.

Agricultural yields have significantly increased in Myanmar’s villages thanks to improved rice seeds and farming techniques. However, abnormal weather and human factors continue to challenge food security. Tzu Chi has introduced the idea of helping others through small, continuous acts of kindness, planting seeds of goodwill in the hearts of local people and fostering a force capable of bringing positive change.

The civil war in Myanmar has affected families’ livelihoods, leaving many children unable to bring lunch to school. Tzu Chi provides meals for students at six schools, using rice from rice banks and vegetables donated by farmers, along with eggs, fruit, and other items, to ensure the children receive proper nutrition and have enough to eat. Photo 1 by Yi Mon Than; photos 2 and 3 by Saw Tho Han Saw