Photo by Liu Zi-zheng

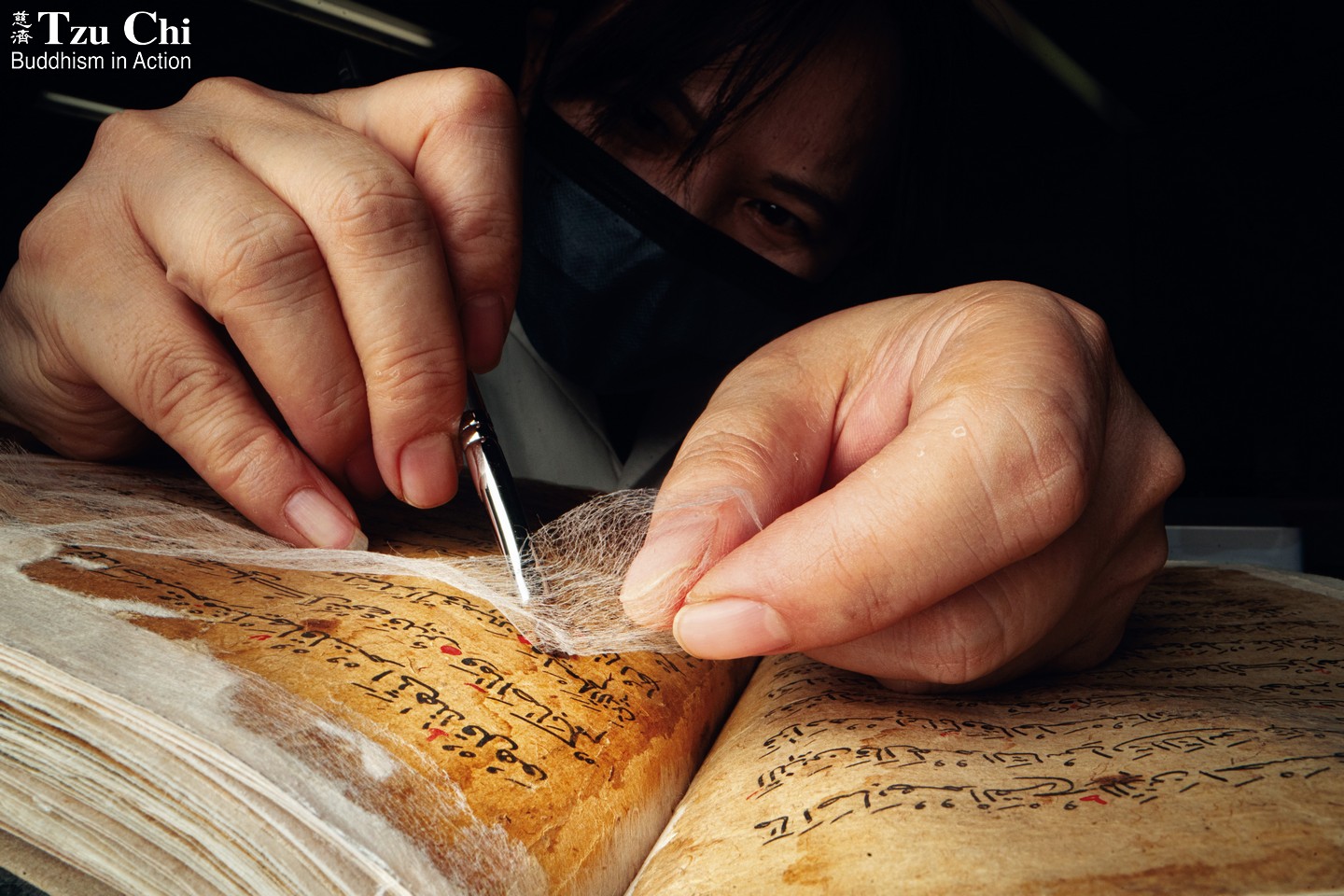

By Jessica Yang and Ning Rong

Compiled and translated by Wu Hsiao-ting

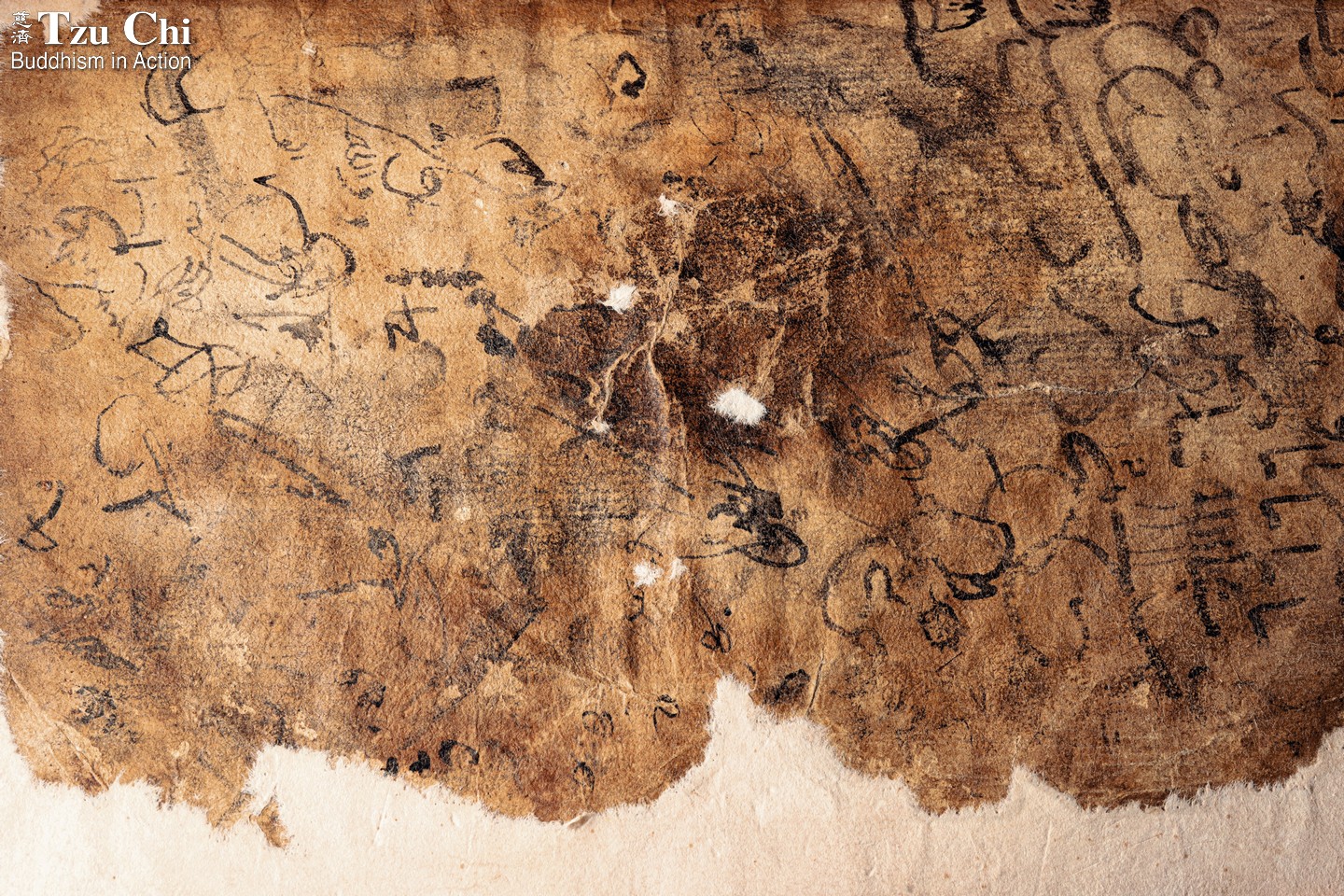

Photos courtesy of the Program Department of Da Ai TV

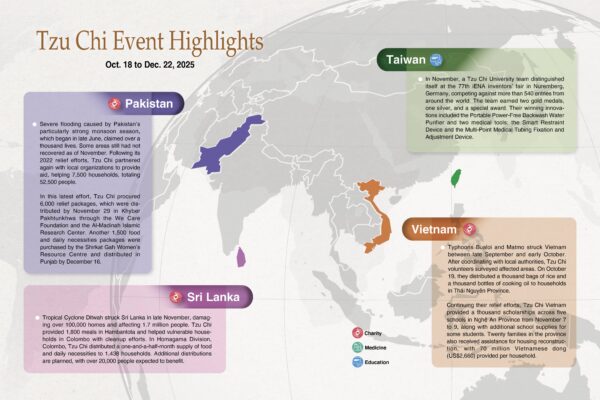

A book restorer works on a 500-year-old handwritten Koran that has suffered damage from bookworms, water submersion, and even fire, aiming to reveal the original appearance of this sacred Islamic scripture.

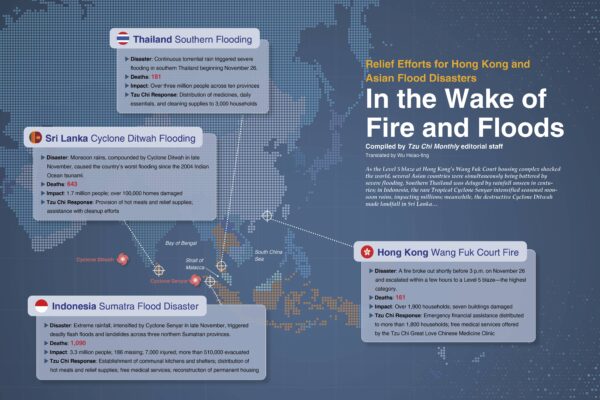

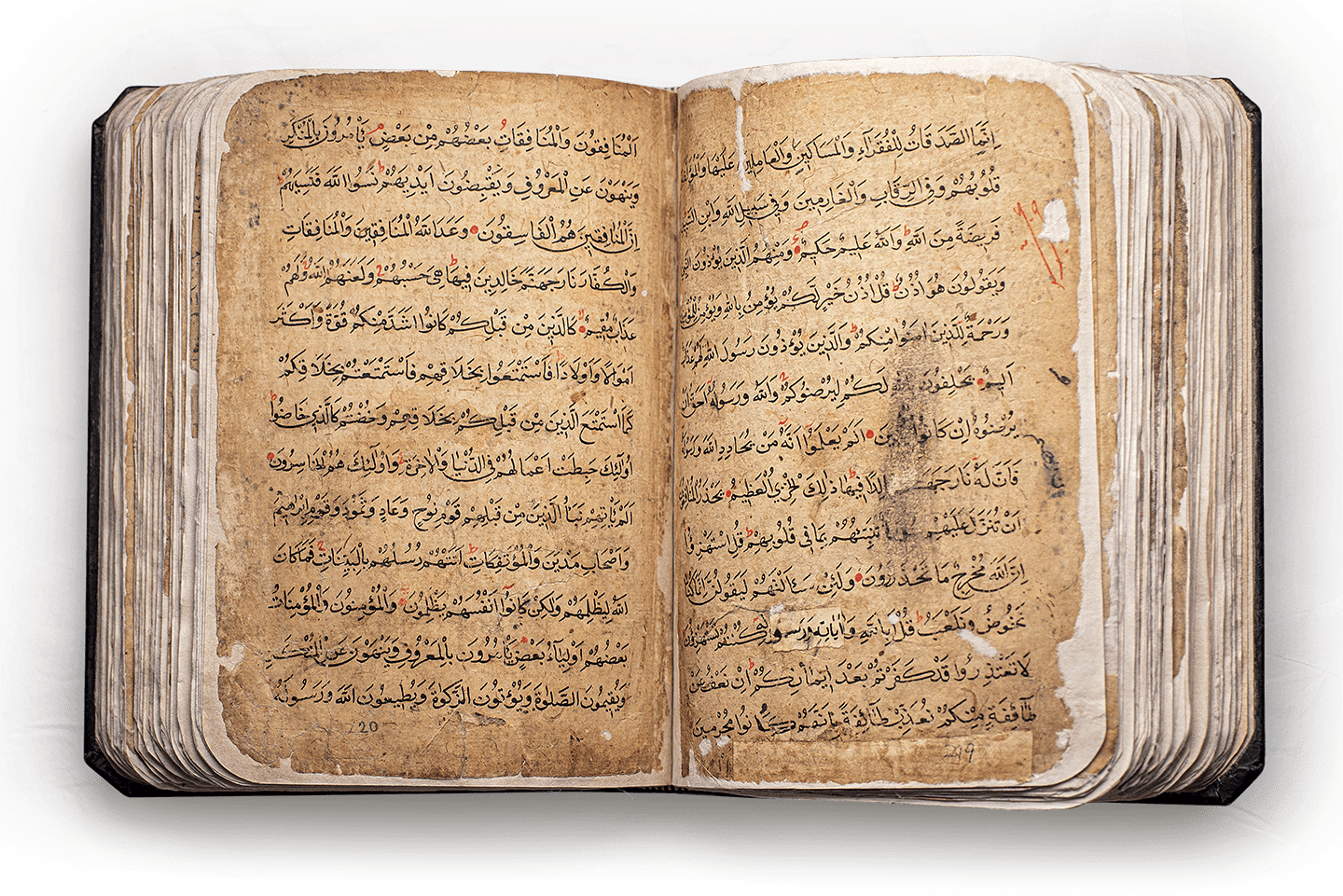

An ancient hand-copied manuscript of the Koran, passed down for hundreds of years, displays different handwriting styles and varying shades of ink on its aged hemp paper.

Liu Zi-zheng

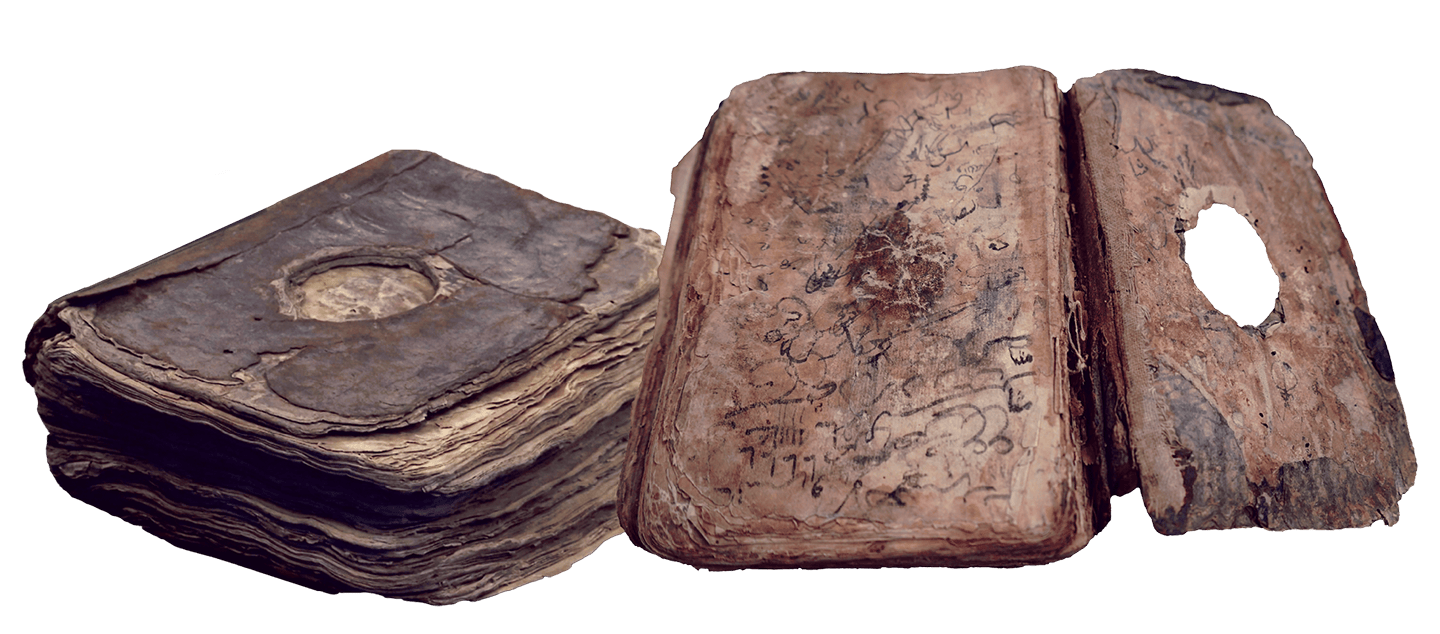

“This is undoubtedly the oldest book I’ve ever encountered, exhibiting multiple types of damage typical of old texts, including from insects,” remarked Xu Mei-wen (徐美文). Xu holds a Ph.D. in Library, Information, and Archival Studies from National Chengchi University in Taipei, and serves as a book restorer at Taiwan Book Hospital, an affiliate of the National Taiwan Library, New Taipei City. She carefully examined what was most likely a 500-year-old handwritten Koran. The cover of the leather-bound tome had become hardened and detached from the main body of the book, displaying the scars of fire, water submersion, burial in soil, and insect infestations. The pages bore traces of blood, mold, mud, flower petals, hair, plant seeds, and insect feces.

“Through deciphering the handwriting and studying other elements of the book,” Xu added, “we are inclined to believe that it was transcribed by ten individuals at different times around the 15th or 16th century. The restoration process poses a significant challenge due to the inconsistencies in the ages and colors of the paper used in the book.”

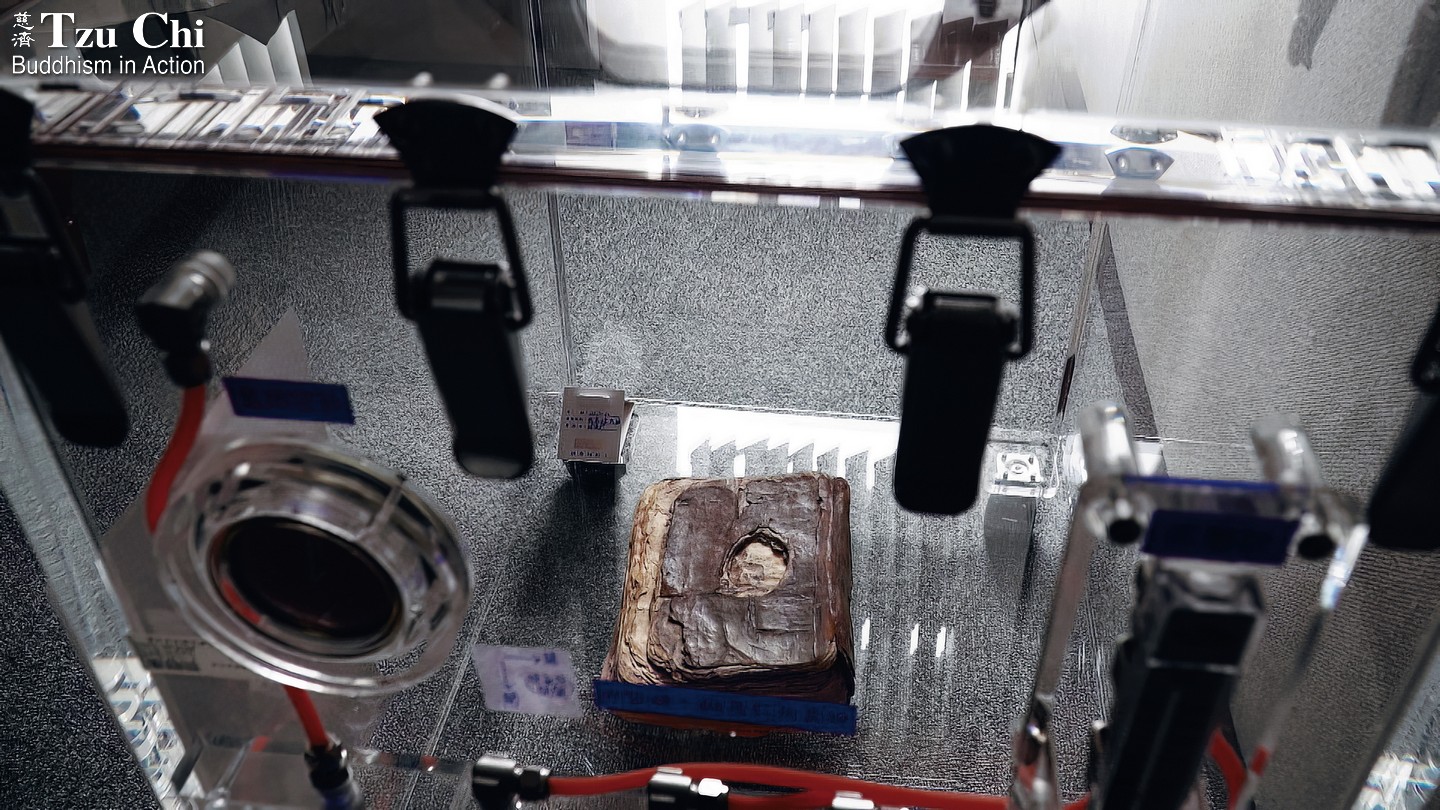

The Koran was found to harbor at least three types of bookworms upon initial examination, necessitating its placement in an anoxic disinfestation chamber for a week-long treatment to eradicate the insects. Afterwards, Xu carefully brushed each page clean with a soft brush. She then renumbered the 500-plus pages of the handwritten Koran before separating the cover from the body of pages. Next, she performed dry cleaning using an eraser and eraser powder. A lot of care was required, and each step of the delicate restoration was very time-consuming. Xu explained that missing even a single step in the meticulous process could jeopardize the outcome.

A Tattered Treasure

This Koran’s front and back covers each have a large hole (Photos 3 and 4). Experts speculate that they may have once been adorned with precious stones. The pages themselves showed extensive wear and tear (Photo 1). The manuscript was infested with three different types of bookworms. There were even what appeared to be insect wings inside the book, later confirmed to be flower petals (Photo 2). In the eyes of restoration experts, it embodied all the pathological conditions that could afflict a book, resembling a critically ill patient. The Koran is a fundamental Islamic scripture, considered to be the divine revelation of Allah. It serves as the cornerstone of the Muslim faith, providing guidance for Muslims’ way of life.

Photos 1 and 4 courtesy of the National Taiwan Library

Restoring old as old

After the book was taken apart and cleaned, one of the biggest challenges followed—finding an appropriate paper for the restoration effort.

Scientific examination plays a crucial role in restoration. Using a microscope, Xu and her team identified three types of paper used in the Koran. They also observed that the fibers in the paper were remarkably long.

Xu has 15 years of experience in cultural relic restoration and has dedicated years to the study of paper. She possesses extensive knowledge of its history. “The paper-making technology in the Middle East was introduced from China during the Tang Dynasty [618 to 907 CE],” she said. The transmission occurred after a group of skilled Chinese papermakers was captured and brought to the Arab world. “During the Tang Dynasty, paper was made from hemp fibers or bark from the paper-mulberry tree. But paper made from tree bark fibers was uncommon in the Arab world, due to the poor growth of trees in the region. Therefore, we have deduced that this Koran was made from hemp paper.”

Paper is a fundamental element in book restoration, but finding a matching modern paper to use proved to be a formidable task. Xu and her team reached out to various paper mills in an attempt to replicate the desired paper but were left empty-handed—none could produce a similar paper. Just when she was feeling stumped, a fortunate recollection came to her aid: she remembered having once purchased some hemp paper, conveniently stored in the National Taiwan Library’s warehouse.

Just like that, in their own warehouse, they found some Japanese hemp paper that closely resembled the thickness and texture of the paper used in the 500-year-old Koran. Moreover, the Japanese hemp paper was produced around the same time period as the Koran’s paper. However, the paper needed to be further processed before it could be used. “The color of the hemp paper was very white,” Xu remarked, “while the color of the Koran’s pages varied in depth. Thus, we needed to find a way to dye our paper to achieve an aged look.” Staying true to Taiwan Book Hospital’s commitment to restoring old books to their aged appearance, Xu took on the task of personally preparing the dye and coloring the hemp paper.

Restoring the Koran involved a methodical step-by-step process. First, the ancient scripture was placed inside an anoxic disinfestation chamber (Photo 1) and infused with 99.9 percent nitrogen for a week to thoroughly eliminate pests. Then, soft-bristle brushes were used to meticulously remove foreign substances (Photo 2). After that, the pages were renumbered, and the book cover was separated from the body. It was followed by a thorough dry-cleaning process using an eraser, moving in a clockwise circular motion (Photo 3).

Painstaking efforts

The National Taiwan Library is nestled beside Number Four Park, in Zhonghe, New Taipei City. The Taiwan Book Hospital is located on the fifth floor of the library. The day we visited, three restoration technicians were meticulously preparing dyes in the Book Hospital. One was fetching water, while another heated dyes in a water bath. Xu, with a dropper and a measuring cup in hand, calculated the precise amount of dye needed. She explained that when they first started to restore the Koran, they estimated the handwritten book to be from the 15th or 16th century. Since the pigments of that time were definitely not modern artificial ones, she made a deliberate choice to experiment with plant dyes and mineral pigments. She recalled, “Initially, I tried using plant dyes and experimented with various plants, such as mixing peppercorns with ink. However, achieving the desired colors remained elusive.” After repeated attempts with plant-based dyes, all unsuccessful, Xu thought of the unique characteristics of the Middle Eastern region, with its plentiful deserts and scarce oases. Consequently, she transitioned to experimenting with mineral pigments. Through various adjustments, she finally confirmed the correct proportions for the formula.

“In the past, masters in the field relied on their experience to dye paper,” she said. “But when it came to restoring the Koran, we didn’t have the guidance of such masters. As a result, we had to start everything from scratch.”

Searching for the right paper, matching its color, and dying it consumed eight months for Xu. Then began the meticulous work of preserving the text on the Koran. For this, she used a Japanese-made, ultra-thin paper called Tengucho and adhered it to the pages of the Koran. Concerned that the moisture from the adhesive might cause the ink to bleed, she slowly pushed, rolled, and pressed the paper onto the pages using wrung-out cotton cloths. This method was a first for Taiwan Book Hospital and the first of its kind in Taiwan.

Xu believes that there is no fixed approach to restoring ancient books. Constant experimentation with new possibilities is necessary to restore old as old. Restoring ancient books is a significant endeavor in preserving cultural heritage. Currently, Taiwan lacks a comprehensive curriculum for training both Chinese and Western book restoration specialists. Restoration workers have to proactively seek guidance from professionals in various fields, much like Xu, who has sought advice from experts in library knowledge, archival aging, archival restoration, and mounting of paintings and calligraphy.

During the restoration of the centuries-old Koran, Xu added an artistic touch to the endeavor using techniques for mounting paintings. Having learned the art of mounting Chinese paintings or calligraphy on paper, Xu applied this approach to repair the Koran’s damaged pages. “I might be the first to treat a book like a painting during the restoration, making each page of the Koran resemble a piece of artwork,” she said. Her gentle and meticulous dedication enhanced the artistic value of this ancient Koran.

Xu encountered numerous challenges in the process of restoring the Koran, from cleaning the book, to mending the pages, to creating a cover. She persevered through all the obstacles. But the hard work was not limited to restoring the book. In reality, her inner struggle was quite profound.

Painstaking Restoration Process

One of the uses of the translucent and delicate Tengucho paper (Photo 1) is for archival conservation. Xu went to great lengths to import it from Japan and adhered it to the pages of the Koran to protect the text. To achieve the aged appearance of the book, she personally crafted dyes and colored the hemp paper chosen for the restoration (Photos 2 and 3). She used mineral dyes after repeated experiments and considering the characteristics of the medieval era and the Middle East. The dyed paper was then air-dried naturally (Photo 4). Various tools like brushes, tweezers, and cotton cloths were carefully used (Photos 5, 6, and 7) during the meticulous restoration process.

Photos 2 and 6 courtesy of the National Taiwan Library

Encountering the Koran

The restoration of the over 500-page Koran proved to be more challenging than Xu had anticipated. “The process was truly agonizing!” she exclaimed. “It took more than two years.” She almost burst into tears when she was nearing completion of the project. “It was a really tough project. I often wondered why I took it on.” At one point, while attempting to restore the cover, she even considered giving up. Nevertheless, she pressed on. “Every time we met with Master Cheng Yen,” she said, “she always showed such respect for us.”

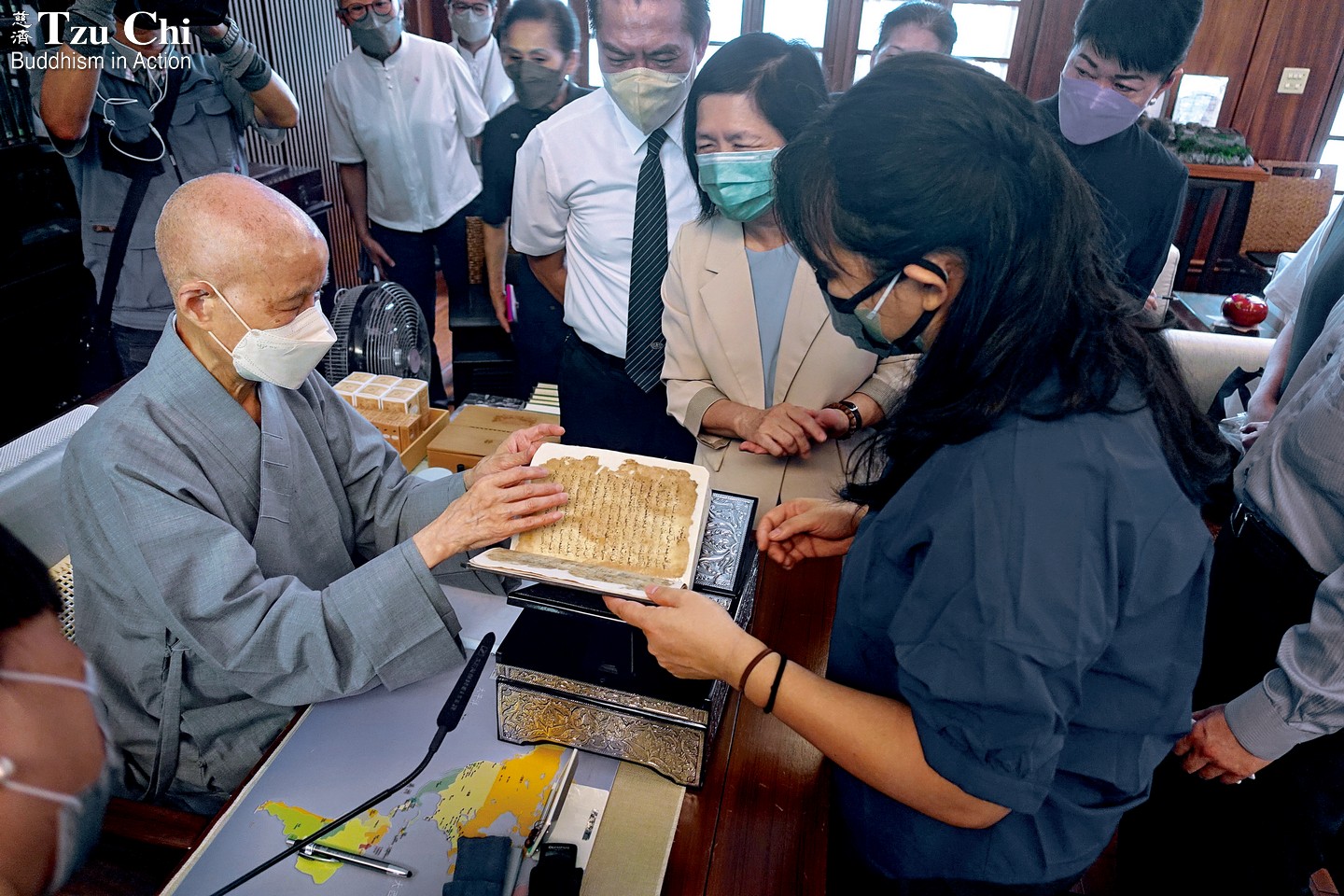

On July 5, 2020, Muslim Tzu Chi volunteer Faisal Hu (胡光中) presented the hand-copied Koran, a cherished piece with over 500 years of history, to Dharma Master Cheng Yen, the founder of the Buddhist Tzu Chi Foundation. The book had been discovered by Hu in an antique books and cultural relics market in Istanbul, Türkiye. While perusing the Koran, the Master noticed that the paper had turned yellow and brittle, and insects were emerging from it. Thus, she conceived the idea of restoration. The Master said after receiving the book, “Although I cannot understand the words in this Koran, its antiquity brings me great joy. Even though our religions are different, our core principles likely share similarities, offering educational and humanitarian value. Therefore, I am enthusiastic about its preservation.” With the assistance of Faisal Hu and another Tzu Chi volunteer, Wu Ying-mei (吳英美), the Koran was delivered to Taiwan Book Hospital for restoration.

Master Cheng Yen’s respect for other religions and selfless Great Love deeply touched Xu. Although not a Buddhist or Muslim, Xu approached the restoration with great reverence for the scripture. She refrained from eating pork and often engaged in inner dialogues with the Koran, feeling as if an unseen force was guiding her forward.

The most challenging task in the restoration of the Koran was restoring the cover. “At first, I wondered whether we should restore the cover at all,” Xu shared. “It was in such bad shape—the leather had hardened and badly cracked. I knew that Master Cheng Yen is a vegetarian and avoids using animal leather. However, if we were to have opted for PU [polyurethane] leather for the cover restoration, we wouldn’t have achieved the same authenticity.” Speaking of this, she expressed gratitude to Master Cheng Yen for her trust in their team and her respect for their expertise. “It really gave us strength to press ahead with the restoration.”

Shortly after the restoration team reported to Master Cheng Yen about the restoration progress of the Koran on November 18, 2022, Xu tried a different method of producing a non-leather cover, leading to a breakthrough. Employing the latest technology from the United States, Xu made a new cover using paper instead of leather. The color matching for the new cover was swift, taking “only” two weeks. Then Xu glued the cardboard cover to the original old cowhide cover, bringing the Koran back to its original appearance.

The restoration of the Koran allowed a precious piece of cultural heritage from the 15th or 16th century to be preserved. It will now be appreciated anew by present and future generations.

Zheng Ying-hang

Cultural heritage

“Why did we dedicate so much time to restoring this ancient book?” Xu asked. “It’s because of its historical significance and the value of the paper. What we undertook was the preservation of cultural heritage. If we failed to properly restore this classic, future generations would have been deprived of the opportunity to appreciate the beauty of these pages, paper, and text.”

Through the restoration of the handwritten Koran, a precious piece of cultural heritage from the 15th or 16th century was brought back to life. The restored Koran is expected to endure for hundreds of more years, possibly a thousand. There’s a heartwarming touch of beauty behind Xu and her team’s dedicated efforts. It now bears witness to the spirit of mutual respect and love among different religions. The act of Master Cheng Yen, a Buddhist, restoring the Islamic scripture reflects a broad and inclusive spirit, leaving a legacy to be remembered and cherished.

Master Cheng Yen examines the restored Koran, a labor of dedication by Xu Mei-wen (in profile) and her team.

Courtesy of the Tzu Chi Foundation