By Wang Ming-meng

Translated by Wu Hsiao-ting

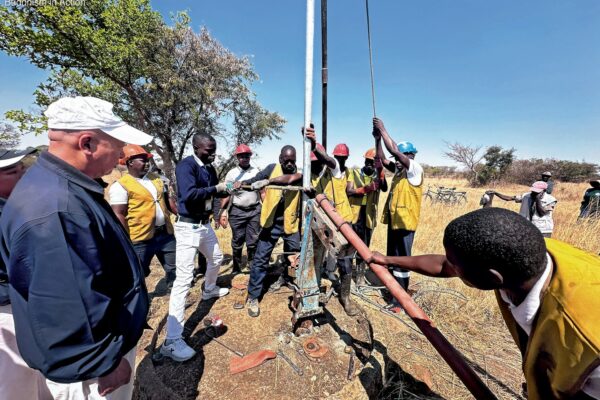

Yang Ma-yun, once an avid angler, repurposed his fishing rods into selfie sticks after joining Tzu Chi. Through this adaptation, he enhances the perspectives of the photos and videos he captures for the foundation.

Clang, clang, clang! The heavy iron hammer, typically used for carpentry, struck with resounding blows, filling the air with scattered shards of carbon fiber. Yang Ma-yun (楊媽允), standing on his balcony, felt not a hint of regret as the five premium fishing rods, valued at about 40,000 Taiwanese dollars (US$1,340) in total, were pounded to rubble in just five minutes. Instead, he felt a weight lifted from his shoulders.

Fish’s tears

Yang hails from Xiyu Township, located in Penghu County, an archipelago off Taiwan’s southwestern coast. In his childhood, he enjoyed fishing and playing by the sea with friends, fashioning simple fishing rods from bamboo and using shellfish as bait. His love for fishing persisted as he grew older. He continued fishing after getting married, when he moved to Taichung, central Taiwan.

As an adult, Yang became obsessed with fishing, always looking forward to the end of the workweek. He was often accompanied by his construction industry friends, fostering camaraderie through shared experiences. Weekends and holidays often saw him with fishing companions, equipped with gear and small coolers filled with ice and refreshments, exploring different fishing spots and having a blast.

One of his longest fishing trips began before sunrise and lasted until sunset. He spent nearly the entire day gazing at the sea, his eyes fixed on the bobber, silently anticipating each catch.

His impressive fishing records made him a popular companion among fellow anglers, who often sought his company for fishing outings. Their favorite fishing spot was Taiwan’s northern coast, where, on weekends, it often felt as though there were more anglers lining the shore than fish in the sea. In the wee hours, hundreds of anglers would gather on breakwaters, holding their breath in anticipation of hooking silver-white largehead hairtail. Bathed in moonlight, the sea’s surface shimmered with the greenish glow of floating bobbers, resembling the flicker of fireflies.

Fish don’t have tear ducts, so they can’t cry. But if they could, the flickering lights on the dark sea’s surface might well have been their glistening tears.

In 2012, Tzu Chi volunteers in Taichung held a Buddha Day ceremony at Summer Green Park. Here, Yang Ma-yun films the rehearsal. Yang Rong-shu

A disciple’s responsibility

In 1998, Yang’s wife, Zhuo Yue-jiao (卓月嬌), visited the Jing Si Abode, a Buddhist convent established by Dharma Master Cheng Yen, the founder of Tzu Chi, in Hualien County, eastern Taiwan. Zhuo saw how the monastics there strove to live self-sufficiently through farming and other work rather than relying on offerings. Their efforts deeply touched her. When she returned home, she eagerly shared her experiences with her husband.

The following year, at the enthusiastic invitation of senior Tzu Chi volunteer Zhou Sha-han (周莎涵), the couple revisited the Jing Si Abode. Amidst its simple and serene surroundings, Yang learned how Master Cheng Yen led her monastic disciples in adhering to the principle set by Master Bai Zhang (百丈, 749-814), a monk in the Tang Dynasty: “If you don’t work, you don’t eat.” Living by this principle, the nuns at the Abode had done all kinds of handiwork to sustain themselves. Even though they had to work hard to sustain themselves and lived an extremely frugal life, they still committed themselves to philanthropic work and initiated the four Tzu Chi missions of charity, medicine, education, and culture.

Moved by this experience, Yang pledged to translate his inspiration into action and share Master Cheng Yen’s burden of caring for the needy around the world.

He seemed transformed after that, eagerly sharing stories of Tzu Chi with everyone he met. He believed it was his duty as a disciple of Master Cheng Yen to spread the word about Tzu Chi, trusting in karmic connections to determine whether others would be inspired to support the foundation. Undeterred by rejection, he shared about Tzu Chi with increasing confidence and conviction.

His leisure time became almost entirely filled with volunteer work for Tzu Chi. His fishing companions gradually drifted away, and the days of gazing at the sea and quietly observing a bobber’s movements naturally faded from his life.

There were other changes in Yang’s life too. After being addicted to cigarettes for three decades, he began to find them increasingly unpalatable and quit without hesitation. He also transitioned to a vegetarian diet. In 2011, Tzu Chi put on a musical adaptation of the Compassionate Samadhi Water Repentance, a Chinese Buddhist text. Participants were required to observe a vegetarian diet for at least 108 days to help purify their hearts and bodies. Yang resolved to quit eating meat after taking part in the adaptation and embrace vegetarianism to maintain a pure body and mind.

Adding wings

In 2003, he became a documenting volunteer, helping record Tzu Chi events and stories, even though he was a complete novice when it came to computers. Starting with basics like powering on/off and typing in Pinyin, he gradually progressed to editing and finishing video segments on his own. His daughter, Yang Li-yi (楊莉怡), remarked, “Sometimes I see my dad meticulously scrutinizing the screen for a long time to perfect just a few seconds of video. His dedication is truly moving.”

One day in 2013, during a study session of documenting volunteers, attendees discussed using a long pole with a microphone attached for filming activities or interviews, which could result in near-perfect sound quality. Suddenly, Yang thought of his large bag of fishing rods at home. After the study session ended, he hurried back home and opened a long-unused fishing gear bag, finding eight fishing rods inside.

Since dedicating himself to Tzu Chi, he had stopped fishing and had no plans to give away the rods. On his balcony, he wielded a hammer and obliterated five of them, deeply remorseful for taking the lives of many fish in the past. He repurposed the remaining three 18-foot fishing rods for filming purposes, equipping two of them with recording microphones and one with a clip for attaching a mobile phone. Using them, it’s as if a microphone or mobile phone has grown invisible wings—they can glide into every corner, capturing touching moments and documenting the world’s goodness.

On August 5, 2023, documenting volunteers from central Taiwan visited the Jing Si Hall in Taichung for a meeting with Master Cheng Yen. “On the count of five, four, three, two, one…recording!” Yang called out. Under Yang’s guidance, the Master pressed the record button. A converted fishing rod of Yang’s, now adorned with a mobile phone, circled the reception room, capturing video of everyone present. It was a rare opportunity to have their images captured with Master Cheng Yen’s. Everyone wore joyful and warm smiles.

Yang Ma-yun displays ingenuity by attaching a wooden board to a small hand truck and securing a video camera onto it, facilitating easier shooting from a low angle. Wu Chen Mei-yan