By Ke Pei-yin

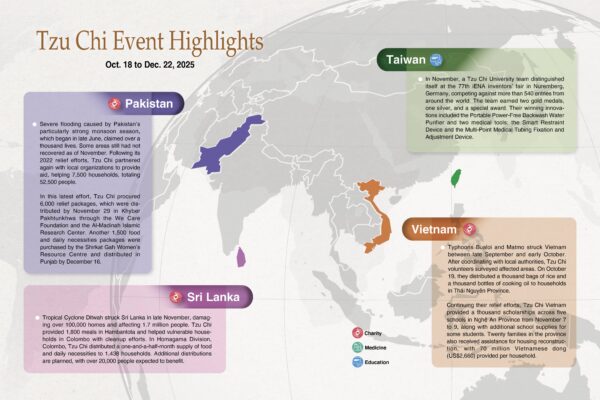

Translated by Tang Yau-yang

Photos by Hsiao Yiu-hwa

For more than half a century, Tzu Chi has worked to make homes safer for needy and elderly people. As the population in Taiwan ages rapidly, so too do many homes. It has become ever more important to make people’s homes safer to prevent falls or other accidents.

The only bathroom at the home of this Tzu Chi care recipient is located outdoors. The bathroom was rendered partially unserviceable and unsafe to use because wind had snapped the electrical wire running to it. Tzu Chi volunteers in Taichung removed the pitaya plant that had wound its way up the nearby utility pole and rewired the bathroom, making it safe to use again.

There is a small park in a quiet alley in the Da’an District of Taipei, frequented by many elderly people in the neighborhood. They come to sit and rest, to chat, to enjoy the warmth of the sun. In contrast to this seemingly cozy picture, however, there is a row of shabby, two-story, corrugated metal houses close to the park. These shanty-looking dwellings don’t seem to belong in this neighborhood of modern high-rise buildings.

Mr. Bao lives in one of the metal houses. He is severely mentally disabled, and has lived alone ever since his mother passed away. He receives a monthly government subsidy for low income households. Tzu Chi volunteers first visited his home in 2006 at the request of the village head, to repair his window screens. They returned the following year, after Typhoon Krosa had blown off his roof, entrance door, and window screens. Volunteers repaired the damage and rewired his house while they were at it.

The households in the row of dwellings where he lives are separated by thin concrete walls. Bao occupies the third unit from the end. Things are piled up neatly around his entrance door and the front hallway is kept quite clean, but the neatness outside belies the sorry state inside. A big hole in the wooden floor in his attic bedroom brings into question the safety of his home. After evaluation, Tzu Chi volunteers decided to help fix up Bao’s home again.

Bao’s living room also serves as a bedroom. A shower curtain separates it from the bathroom and kitchen. There is little privacy to speak of in the housing arrangement, but Bao has long become accustomed to it.

Volunteers hold a housewarming party for Bao (in pink shirt) after the remodeling of his home was completed.

Preventing risk of a collapse

A group of volunteers visited Bao one day to conduct a thorough inspection of his home and determine what repairs were necessary. A moldy odor greeted them before they even stepped into the house. Once they were inside, the sight and the stench quickly made them realize that Bao eats, drinks, and goes to the bathroom here. The kitchen and the bathroom were just beyond the living room, separated by a shower curtain. There was nothing at all to separate the kitchen from the bathroom. Obviously, a bathroom door was needed for hygiene and privacy; it was one of the first things the volunteers decided to install.

Volunteer Chen Hong-lin (陳宏麟), a 40-year veteran in interior decorating, noticed that the tiles on the sink in the kitchen had fallen off. He suggested replacing the tile sink with stainless steel. Such a sink would be durable and easy for Bao to maintain.

Chen then examined the broken attic floor and the damp, decaying, moldy stairs leading to it. “The wooden stairs to the attic can be replaced with steps of galvanized steel,” he said, “and we can replace the plywood attic floor with a C-beam base covered with plastic flooring. There will no longer be any danger of a collapse by the time we get done with it.”

Tzu Chi volunteers had repaired Bao’s roof before, but the metal sheets they had installed then did not have enough overhang to stop rain from splashing into the house during typhoons or rainstorms. Chen measured everything and decided to extend the metal sheets to ensure that the roof would keep out even the “cats and dogs” kinds of rain.

Generally speaking, a house becomes an “old house” after 30 years; a 50-year house would be considered a ”super-old house.” Statistics from Taiwan’s Ministry of the Interior in the first quarter of 2020 pegged the average age of houses in Taipei at 34 years, with 77,000 super-old houses in the city. Although advancing age is traditionally one of the main reasons for house repairs, the large number of old houses in Taipei has not led to a surge in requests from the needy for Tzu Chi assistance in home repairs.

Why is there such a discrepancy between the number of older houses and the number of repair requests? “Most of the recipients of our long-term care are renters, not property owners,” senior volunteer Zeng Mei-hui (曾美惠) said. She added that any remodeling proposals must be negotiated with property owners, a back-and-forth process that can be quite time-consuming. It makes more sense to make other arrangements for care recipients if their rentals require major overhauls, such as convincing them to move to another place, than to go through the process of renovating a rental unit.

Zeng went on to explain that though some care recipients are not renters, they live in houses built on land they don’t own themselves. When that happens, volunteers must consult with the lawful owners of the land and buildings before they proceed with any renovations. This prevents legal issues down the road. And once the remodeling has started, volunteers must pay attention to an array of details to keep things moving forward positively. For example, they must strive to not disrupt or trouble people living nearby. All this goes to show that a remodeling effort involves much more than just making the physical renovations to a house.

Volunteers arrived at Bao’s house one day in early July to prepare for a one-month renovation. They cleaned up the house, packed up Bao’s belongings, and together with Bao, his sister, and her husband, moved larger furniture out of the place before covering it in waterproof canvas. The remodeling team arrived the next day and began working. They first took apart the wooden floor of the attic. They removed nails and other supporting mechanisms until the whole floor dropped to the ground, causing a big dust cloud that made everyone around sneeze nonstop.

After cleaning up the mess, the team measured, cut, and installed C-beams in the attic. A sturdy floor began to take shape. When they were done with the floor, they set to work replacing the rotten wooden stairs that led up to the attic with galvanized steel steps. They measured, welded, drilled holes, and screwed carefully. Chen Hong-lin inspected the workmanship every step of the way to ensure quality.

Respecting what residents want while ensuring safety

Tzu Chi has been making home improvements for the disadvantaged in Taiwan for more than half a century. In response to the rapid aging of Taiwanese society, the foundation is looking to further extend this service to benefit more people. In recent years, Tzu Chi has advanced home safety improvement projects from a prevention point of view. With help from village or neighborhood heads, volunteers have been trying to reach more elderly and disabled people to help them improve the safety of their homes.

Some older people in Taiwan would rather remain in their old homes in the countryside than move in with their children out of town or check into retirement homes. They often end up living alone as a result. To save money, they may continue to use old-fashioned squat toilets even though they have difficulty standing up from a squatting position. To save electricity, they may be reluctant to turn on lights. Moving around in their poorly illuminated homes makes them vulnerable to falls and other hazards. They stick to their routines and are often loath to ask others for help. Seeing their needs, Tzu Chi volunteers have taken the initiative to reach out to them and senior-proof their homes.

Close to 30 percent of residents are elderly in Pingxi District, New Taipei City, northern Taiwan. With the assistance of the city’s Departments of Social Welfare and Civil Affairs, Tzu Chi volunteers went to work in this highly aged district. They made their first home visits in Pingxi to identify people who needed home improvement services in mid-May 2020. They were accompanied by Pan Long-yu (潘隆裕), chief of the Shulang neighborhood, and Gao Shu-lian (高淑蓮), of the Social and Humanitarian Section of the district office.

Mr. and Mrs. Zhan have six children, all of whom have their own families and live elsewhere. The elderly couple lives alone in a one-story house surrounded by woods in Shulang. They were sitting and chatting outside their home when the group of visitors arrived. During their visit, Tzu Chi volunteers tried to convince the couple to allow the installation of grab bars in their bathroom to reduce the risk of falls. The couple looked shy and embarrassed during the conversation; they were reluctant to go along because they didn’t want to trouble others. Only after the volunteers repeatedly reassured them that it would be no trouble at all did the couple agree to have grab bars installed in their bathroom.

Li is another older resident of Shulang. She lives alone. Like the Zhans, her children live out of town. Volunteers assessed her home and planned to install safety handrails in places where the risk of falls was the greatest. They also planned to build some steps to bridge the elevational gap between the floor and the threshold, a gap that the volunteers worried might cause her to trip and fall. But Chen Zhi-ming (陳志明), a Tzu Chi social worker, pointed out that such a change could itself be more dangerous than no change at all. Unused to the added steps, Li might be more likely to trip and injure herself. The volunteers thus decided to discuss this adaptation with Li more thoroughly before they went ahead with anything.

One day in mid-July, before the sun got too hot, Tzu Chi volunteers made another visit to Shulang to install grab bars in six households. At the Zhans’ home, volunteer Lin Shi-jie (林世傑), a professional mason, used a wall scanner to locate hidden electrical wires and water pipes behind the walls in the bathroom. This enabled them to avoid drilling into them during the installation. Lin and other volunteers mounted a grab bar by the toilet and another one by the washbasin. Two hours later, they moved on to Li’s house.

Li was standing at her door to greet the volunteers before they had even parked their car. The team first installed a grab bar in Li’s bathroom, which was separate from the main building. Then they replaced the old, worn lighting fixture in the bathroom, and relocated the switch so that Li would no longer need a stool to reach it. Reaching high places is a safety hazard. “You’re very considerate,” said Li to the volunteers. After she had tried the grab bar, she was so happy she couldn’t stop smiling.

Improved indoor lighting and added grab bars make Li’s home, in New Taipei City, safer to live in.

Volunteer Lin Shi-jie (left), a professional mason, examines the wall with a wall scanner to avoid electrical wires and water pipes before installing grab bars in the bathroom. Zhan, the house owner, looks in curiously from the door.

Similar home safety improvements for the elderly have been carried out in Dongshan, Beitun District, Taichung City, central Taiwan. Dongshan is also home to many older people. Near the end of May, more than a hundred people, including Tzu Chi volunteers, gathered in front of a community activity center in the neighborhood. They divided themselves into seven groups before fanning out to visit 19 households, which were located mainly in the mountains or in small alleys. Neighborhood chief Qiu Cai-yuan (邱財源) and his associate Liu Cun-rong (劉村榮) led the way.

A car carrying some of the visitors bounced along a winding, uneven mountain road, headed toward the home of villager Xu. After the group of people got out of the vehicle, they carefully negotiated a wet, mossy, steep slope before arriving at Xu’s home. A constant smile played on the elderly woman’s lips—perhaps because she had not seen so many visitors in her home all at once in a long time.

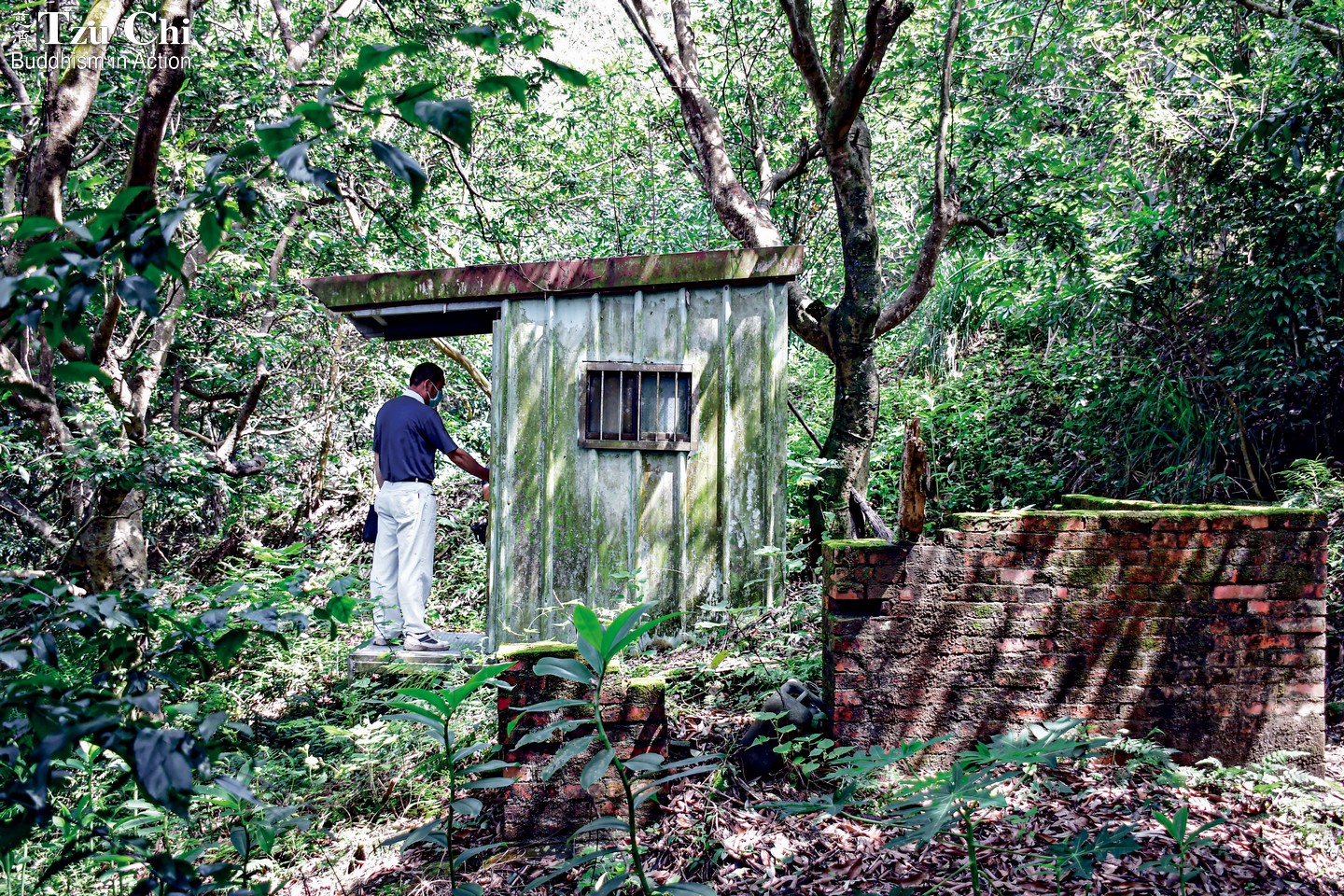

Xu’s children did not live with her. She lived alone in a one-story house that was about 60 years old. The house was set in the middle of a sea of trees. Sunlight could not easily reach it, making it damp and dark even on a sunny, bright day. On a cloudy day, the house became even darker. The roof, long in disrepair, leaked badly in the rain. The lavatory was situated on a steep slope more than 30 meters (100 feet) from the house. Xu had to cross a small bridge just to reach it, and the path had neither lights nor guardrails. At night, Xu had to feel her way in the darkness to answer nature’s call. She had even been bitten by snakes on her way to the lavatory before. To improve safety, volunteer Ye Wen-an (葉文安) suggested to Xu that she let them install a toilet in her shower room, which was not far from the house. But Xu declined the offer for help, saying that she was accustomed to the current arrangement.

As much as 90 percent of Dongshan, Beitun District, Taichung, is hilly. Xu’s lavatory was built on a steep slope more than 30 meters (100 feet) from her house. The way leading to the lavatory had neither lights nor guardrails. Volunteers visited her at her home in late May to assess how to make improvements to her living environment. PHOTOS BY LIU JIN-LONG

During another visit in June, volunteers Ye Wen-an (left) and Cai Ming-mo (蔡明模, second from right) and neighborhood chief Qiu Cai-yuan (third from right) discuss the possibility of adding a bathroom next to Xu’s bedroom. PHOTOS BY LIU JIN-LONG

Small repairs prevent big falls

During similar home visits in Taipei and Taichung, volunteers have noticed that many elderly folks tend to decline Tzu Chi’s offer to senior-proof or remodel their homes for improved safety. Qiu Cai-yuan, Dongshan neighborhood chief, cheered the volunteers on nevertheless. He reasoned that more frequent visits might change the minds of the elderly.

That proved true in Xu’s case. Volunteers visited her again in mid-June. Her daughter was there this time. The volunteers explained to both how they hoped to remodel the house to make it safer. Their enthusiasm and perseverance finally won Xu over. She agreed to the remodeling, which would include repairs to her roof and the addition of a new bathroom next to her bedroom. Soon, the shower and toilet would be in one place and much closer for her to use.

In contrast to the lukewarm reception in other cities, requests for remodeling services in Tainan, southern Taiwan, have risen threefold. Why the difference? Staffers who process all of Taiwan’s residential safety improvement projects at Tzu Chi’s Department of Charity Mission Development in Hualien explained the reason for the increase in requests. They said that the efforts of neighborhood heads and volunteers in promoting and implementing remodeling plans have changed the minds of some elderly folks. Though such folks didn’t want to burden their children, they shunned the remodeling help as a handout for the poor. But once neighborhood heads and volunteers convinced the folks that their projects would improve their safety at home, they willingly began signing up in droves. The elderly folks realized that taking good care of themselves was the best way to put their children at ease and keep them from worrying.

Some social welfare organizations in Taiwan also provide home improvement assistance like that offered by Tzu Chi. The Heng-Shan Social Welfare Foundation is one such group. In the process of helping mentally challenged people gain the ability to take care of themselves, personnel there learned their homes are often a big mess. This is because their illness prevents them from sufficiently caring for themselves or their homes. In May 2014, the foundation established the Heng-Shan Good Deeds Group, whose mission is to improve the living environment and safety of disadvantaged households with disabled members.

The Eden Social Welfare Foundation started offering home improvement assistance to disadvantaged families in 2009. In 2017, this foundation founded the Live Well Home Repair Group in response to the growing ranks of elderly people living alone, elderly couples living alone, and elderly folks staying home alone while their children worked during the day. They knew that home improvements could lower the risk of accidents at home and consequently help prevent loss of function in older people, which is a good thing for society.

The success of the Tzu Chi Foundation senior-proofing and remodeling service undoubtedly relies heavily on volunteers who work with the needy. But there are only so many of them, and there is just so much that they can do. It is the foundation’s hope that more like-minded people and home renovation professionals will join to strengthen this service to the needy.

Su Jia-hui (蘇家慧) works in Hsinchu, northern Taiwan. After a friend told her about Tzu Chi’s home improvement service, she accompanied some volunteers on a visit to Xu’s home. Xu speaks Taiwanese, a dialect Su doesn’t understand well. Though she could not understand much of the conversations during the visit, she quietly observed the interactions between the volunteers and Xu. She was shocked by Xu’s living conditions during the visit, and she felt very sorry for her. The trip helped her realize that her own circumstances were much better than those of many other people. It made her even more grateful for what she had.

In early August, a group of volunteers in Taipei held a housewarming party for Bao, mentioned at the beginning of this article. They cooked tangyuan (small glutinous rice balls) and a nice lunch for the happy occasion. The unceasing rain outside did nothing to dampen the joy, fun, and laughter inside the house. Volunteers also went with Bao to give tangyuan and apples to his neighbors, to thank them for looking out for him over the years.

Bao was all smiles as he inspected his remodeled bedroom. With the new floor, he could now finally sleep soundly at night.

“In the past, when he took a step on the wonky stairs, my heart would skip a beat,” said a volunteer. Now looking at Bao stepping on the sturdy stairs, volunteers can finally put their minds to rest.