By Wei Yu-xian and Jiang Yu-ping

Compiled and translated by Wu Hsiao-ting

Photos by Jiang Yu-ping

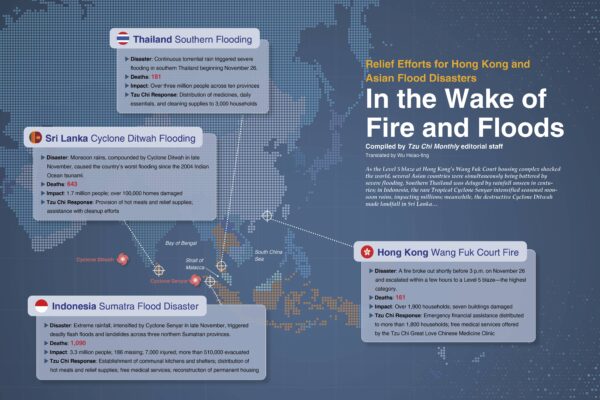

Over the past two decades, 3,000 students have graduated from Chiang Mai Tzu Chi School in northern Thailand. The school’s aim is not merely to help its students fly high, but to help them fly far, fly steadily—and become the wind that lifts others.

Teachers tie white cotton strings around graduating students’ wrists as a blessing during this year’s Chiang Mai Tzu Chi School junior and senior high graduation. Lin Ying-qin

It was a tragic chapter in history, born out of the upheaval of a turbulent era. In 1949, after the Nationalist government retreated from China to Taiwan following its defeat by the Chinese Communists, a unit of the Nationalist army—composed primarily of soldiers from Yunnan, southwestern China—moved to the northern border of Myanmar and continued their fight. They eventually retreated into the mountains of northern Thailand and settled there.

Scattered across the hills, these soldiers and their families built villages made up of thatched huts and stilt houses. Inside, a few hardwood benches and basic cooking utensils comprised the entirety of their possessions. Without Thai citizenship, they lived as stateless refugees, unable to seek legal employment. Their survival depended on small-scale farming on poor soil, which yielded little. The villages lacked even the most basic services—no electricity, running water, or medical care.

In early 1994, John Chiang (蔣孝嚴), then Minister of Taiwan’s Overseas Chinese Affairs Commission (now the Overseas Community Affairs Council), visited Dharma Master Cheng Yen at the Jing Si Abode in Hualien, eastern Taiwan. He explained that the Taiwanese government’s aid program for the refugees in northern Thailand would end later that year and appealed to Tzu Chi to take over the support efforts. In response, Tzu Chi dispatched assessment teams on two separate occasions to conduct on-site evaluations. The following year, the foundation launched a three-year assistance program that included building homes, offering agricultural guidance, and providing care for the veterans.

Through this work, the foundation came to recognize the vital role of education in improving long-term prospects for local children. Consequently, at the end of the three-year program—and while continuing support for the veterans—Tzu Chi embarked on a project to build a school in Fang District, Chiang Mai.

Construction of the elementary division of Chiang Mai Tzu Chi School began on April 27, 2002, on land provided by the local government. The school officially opened on May 16, 2005, becoming Tzu Chi’s first overseas school. By 2013, it had expanded to offer a full curriculum from first grade through high school. Although located in a remote mountain area, the school offers trilingual instruction in Thai, Chinese, and English, equipping students with the skills needed to engage with the international community. The school now has over 80 teachers and more than 1,100 students. Over 3,000 students have graduated from the school in its 20 years of operation.

From student to entrepreneur

This year marks the 30th anniversary of Tzu Chi’s work in northern Thailand, as well as the 20th anniversary of Chiang Mai Tzu Chi School. In March, I, an employee of Da Ai TV, joined a Tzu Chi team from Taiwan on a visit to northern Thailand. One part of our itinerary was to attend the school’s junior and senior high school commencement ceremony. I was also tasked with interviewing several alumni for a feature segment.

Before the interviews, I wondered: Can education truly change a person’s future? The school has been nurturing students for 20 years. Have the children who once studied there found their place in the world?

Our first stop was Samut Prakan Province, south of Bangkok, a region known for its many factories and industrial zones. There, we met Jing Wen-liang (景文亮), one of the earliest graduates of Chiang Mai Tzu Chi School. Now 30, he is in his fourth year as an entrepreneur, the founder of a bottled water company.

My first impression of Jing was from an old video clip, before I had met him in person. He was in 11th grade at Chiang Mai Tzu Chi School at the time, speaking during a Chinese class. When the teacher asked the students to use the word “future” in a sentence, Jing stood up and declared with confidence, “In the future, I want to be a boss!” His declaration stayed with me.

When we finally met, he spoke with our team as if we were longtime friends—relaxed, self-assured, and warm. That same ease, I thought, might be what helped him navigate the challenges of building a business from the ground up.

His factory spans about 20,000 square meters (4.9 acres) and consists of three buildings that operate around the clock. He employs 83 people, 90 percent of whom are migrant workers from Myanmar. Many of these migrant workers don’t speak Thai and lack legal status, leaving them particularly vulnerable to exploitation. To protect them, Jing helped each one obtain a legal work permit and provides low-cost dormitory housing. “I’m a Chinese descendant from the mountains in northern Thailand,” he said. “I know what it’s like to live without choices.”

Bottled water production demands precision; any misstep in the process can result in major losses. Although language differences can be a challenge, Jing remains calm. Smiling, he explained, “Each line supervisor can speak a bit of Thai. We divide the work among small teams, so I only need to communicate with a few key people.” That confidence and easy command of things harken back to his school days. “Our teachers used to take us out for volunteer work,” he said. “We ran into all kinds of unexpected problems, and we learned to figure them out on our own.”

Back at our hotel, I noticed that the bottled water in our fridge came from Jing’s factory. I reflected on the journey behind his business: he had begun with only one machine and had slept on the factory floor in those early days, gradually expanding his operations through sheer hard work. “The sound of the machines was like my lullaby,” he said. “Whenever they stopped, I’d wake up.” His success is built on persistence, long nights, and learning from trial and error. One can’t help but admire this young man—not just for what he’s built, but for the spirit that has carried him through.

Jing Wen-liang instructs a worker on operating machinery at his bottled water factory. As a descendant of northern Thailand’s Chinese community, he is mindful of protecting migrant workers’ rights.

Lifting others as they rise

Weng Jian-ting (翁建廷) was also among the first graduates of Chiang Mai Tzu Chi School. Today, he works as a creative director in the computer animation industry, leading a team of 30. He has a boyish charm but his glasses give him a bookish air.

Weng’s first encounter with the school came when he accompanied a friend to enroll. The moment he set foot on campus, he was captivated by the large trees in front of the school buildings and the mountain winds rustling through their leaves. But what ultimately led him to enroll was more personal. Raised by a single mother, he was deeply moved by how hard she worked to support the family alone. Choosing to study and live in a remote area was his way of easing her burden. Life in northern Thailand meant lower living expenses and less pressure. “I wanted to make things a little easier for my mom—and also become a little more independent,” he said.

Visual storytelling had always been his passion. When he was a student at Chiang Mai Tzu Chi School, he took on nearly every filming and editing task, from documenting events to producing graduation videos. His teachers supported his interests and provided the resources he needed to explore them. Over time, that passion became his profession. He even created Thailand’s first free online animation learning website, giving children with limited resources a way to step into the world of digital animation.

Looking back on his school days, he said, “Volunteering taught me more than any class ever did. We visited nursing homes and remote villages. Those real-life experiences taught me how to understand people.” Like Jing Wen-liang, he credited volunteer experiences with shaping who he is today.

We also interviewed 26-year-old Chen Ji-chang (陳吉昌), an alumnus who now serves as a firefighter in Fang District. He recently passed the national teacher qualification exam and is awaiting a placement.

On the day we met him, he was preparing for a wildfire prevention mission in a national forest reserve. He moved with a steady, purposeful stride in his uniform, but spoke in a tone that was humble and gentle. Asked why he chose to become a firefighter, he recalled a moment from his school days. Back in high school, Chiang Mai Tzu Chi School had invited firefighters to speak. “After listening to them, I just knew I wanted to do something like that, something that helps people,” he said.

As for his interest in teaching, he credits his own teachers: “I hope to eventually return to a remote area to teach. I want to carry forward and pass on the spirit of the people who once helped me—the teachers who encouraged me to keep going.”

These alumni share something in common: they don’t run from their roots. Instead, they look back with gratitude—and they give back. They’re not only focused on their own success. They also want to be part of the wind that helps lift others.

Weng Jian-ting, a creative director in computer animation, once launched a free website to help children with limited resources explore the world of digital animation.

Now a firefighter, Chen Ji-chang was inspired by teachers at Chiang Mai Tzu Chi School to earn a teaching certification. He hopes to teach in remote areas, passing on the support he once received.

Deep bonds

Before visiting Chiang Mai Tzu Chi School, I never imagined I would shed so many tears at a graduation ceremony in a foreign country.

A gentle breeze wafted across the campus that evening, as all the graduating junior and senior high school students gathered in front of one of the school buildings. They sang and danced, their movements a little awkward, but their smiles bright and unrestrained. It was the spirit of youth, blooming freely in the twilight. Guests from both Thailand and abroad, including monastics from the Jing Si Abode, couldn’t resist pulling out their phones to capture the moment. Some even turned on their flashlights, waving them in time with the music.

As the ceremony drew to a close, a special ritual took place: teachers tied white “blessing strings” around the graduates’ wrists. This Thai Buddhist ritual symbolizes purity and blessings. Each student received five cotton threads and invited five teachers who had deeply influenced them to tie them on.

The cheerful atmosphere gave way to a deeper emotional current. More than a hundred graduates knelt quietly in lines, waiting their turn. The teachers, seated in low chairs, busily tied the threads, softly uttering each student’s name and offering words of encouragement. The students expressed their gratitude and love—and even apologies, asking for forgiveness for their youthful rebellion or defiance.

I still remember a boy, nearly 170 centimeters (5’7”) tall, sobbing in the arms of a male teacher. The teacher’s eyes were red too. As he tied the thread, he gently whispered something. I didn’t know their names, but the boy’s tears spoke of a genuine trust, a silent but powerful testament to their bond.

In that moment, a thought came to me: if every child could have a teacher like this—someone who truly understands and loves them—then regardless of where life took them, they would always carry the knowledge that they are worthy of love and care.

Not alone

In one corner of the graduation ceremony, teacher Huang Ya-chun (黃雅純) knelt beside a petite girl and gently asked, “Are you happy?” The girl, ninth-grade graduate Bao Shu-san (包書叁), nodded.

“You weren’t happy during your first two years at the school, were you?” the teacher continued. “Life doesn’t have to be so complicated. If you keep worrying about things before they even happen, you’ll only make yourself unhappy.” Her voice was calm and steady, as if she could see straight into the girl’s heart. “At your age, it’s okay to take things a little more lightly,” she added. “Try to practice that in high school, okay?”

The teacher’s advice moved me. She must have been paying close attention to Bao—caring for her, watching over her—otherwise, how would she have known just what to say to reach her inner world?

Bao was once a stateless refugee student and obtained legal residency only last year. With the help of Tzu Chi scholarships, she and her younger brother were able to enroll in the school. When she first arrived, she was malnourished and frail, but her health gradually improved after she moved into the school dormitory. She excelled academically and maintained a disciplined routine. Her teachers described her as a highly promising student.

The director and camera assistant with me had filmed Bao last year as part of their coverage of the school. I asked them, “Do you think she’s changed from when you saw her last?” They both nodded without hesitation. “She smiles more now, and looks more confident,” one of them said.

When I asked Bao about her dreams, she told me she wanted to become a doctor. As a child, she had needed surgery, but her family couldn’t afford it. A charity stepped in and helped her through that difficult time. She’s never forgotten their kindness and hopes to pay it forward.

Her parents couldn’t attend the graduation ceremony. Though she tried not to show it, her sense of loss was unmistakable. Back at the dormitory, I took out a folder I had bought before the trip. It had a cute design, and though it was simple and inexpensive, I gave it to her as a graduation gift—a small gesture to let her know she’s not alone. I want her to know that wherever life takes her, there are people who care about her and are quietly cheering her on.

Bao Shu-san, who graduated from junior high this year, received surgery as a child with help from a charity. She aspires to become a doctor to help others.

Passing on the light

Just when we thought the event was over and had wandered to another corner of campus, we were met by a breathtaking sight: the entire central atrium glowing softly with candlelight. Curious, I asked a nearby teacher what was happening. He smiled and shook his head, saying, “I don’t know either—I’m just here to enjoy the show.”

As I soon learned, the event is a tradition at the school. Every year, the 11th-grade students secretly plan a surprise for the graduating seniors. The entire surprise is planned, organized, and executed by the students themselves, without any help from the teachers.

Soon, the graduating seniors, blindfolded, were guided into the atrium, each placing a hand on the shoulder of the person in front. When their blindfolds were removed, they were met with a sea of candlelight and a projection screen showing clips their younger schoolmates had secretly recorded—moments of them reading in the classroom, daydreaming in the hallway, or laughing on the sports field. Each scene captured the radiance of youth.

That night in the atrium, there were no empty slogans—only genuine blessings, heartfelt gratitude, and the quiet sorrow of parting. This surprise wasn’t meant to impress; it was a lesson in passing on the light.

More than 3,000 students have graduated from Chiang Mai Tzu Chi School over the years, each taking their own path in life. They work in various professions and earn different incomes. But the important thing isn’t how much they earn or what they do, it’s what they carry within themselves: a heart that cares for others. That’s something to be truly proud of.

A school’s true achievement isn’t measured by rankings or college admissions. It’s whether students leave knowing how to love, take responsibility, and see the needs of others.

This, I believe, is the essence of Tzu Chi’s humanistic education: it’s less about teaching children how high to fly, and more about teaching them how to fly far, fly steadily, and light the way for others.

(Translator’s note: the English names of the people mentioned in this article are transliterations of their Chinese names.)