Converted Fishing Rods

By Wang Ming-meng

Translated by Wu Hsiao-ting

Yang Ma-yun, once an avid angler, repurposed his fishing rods into selfie sticks after joining Tzu Chi. Through this adaptation, he enhances the perspectives of the photos and videos he captures for the foundation.

Clang, clang, clang! The heavy iron hammer, typically used for carpentry, struck with resounding blows, filling the air with scattered shards of carbon fiber. Yang Ma-yun (楊媽允), standing on his balcony, felt not a hint of regret as the five premium fishing rods, valued at about 40,000 Taiwanese dollars (US$1,340) in total, were pounded to rubble in just five minutes. Instead, he felt a weight lifted from his shoulders.

Fish’s tears

Yang hails from Xiyu Township, located in Penghu County, an archipelago off Taiwan’s southwestern coast. In his childhood, he enjoyed fishing and playing by the sea with friends, fashioning simple fishing rods from bamboo and using shellfish as bait. His love for fishing persisted as he grew older. He continued fishing after getting married, when he moved to Taichung, central Taiwan.

As an adult, Yang became obsessed with fishing, always looking forward to the end of the workweek. He was often accompanied by his construction industry friends, fostering camaraderie through shared experiences. Weekends and holidays often saw him with fishing companions, equipped with gear and small coolers filled with ice and refreshments, exploring different fishing spots and having a blast.

One of his longest fishing trips began before sunrise and lasted until sunset. He spent nearly the entire day gazing at the sea, his eyes fixed on the bobber, silently anticipating each catch.

His impressive fishing records made him a popular companion among fellow anglers, who often sought his company for fishing outings. Their favorite fishing spot was Taiwan’s northern coast, where, on weekends, it often felt as though there were more anglers lining the shore than fish in the sea. In the wee hours, hundreds of anglers would gather on breakwaters, holding their breath in anticipation of hooking silver-white largehead hairtail. Bathed in moonlight, the sea’s surface shimmered with the greenish glow of floating bobbers, resembling the flicker of fireflies.

Fish don’t have tear ducts, so they can’t cry. But if they could, the flickering lights on the dark sea’s surface might well have been their glistening tears.

In 2012, Tzu Chi volunteers in Taichung held a Buddha Day ceremony at Summer Green Park. Here, Yang Ma-yun films the rehearsal. Yang Rong-shu

A disciple’s responsibility

In 1998, Yang’s wife, Zhuo Yue-jiao (卓月嬌), visited the Jing Si Abode, a Buddhist convent established by Dharma Master Cheng Yen, the founder of Tzu Chi, in Hualien County, eastern Taiwan. Zhuo saw how the monastics there strove to live self-sufficiently through farming and other work rather than relying on offerings. Their efforts deeply touched her. When she returned home, she eagerly shared her experiences with her husband.

The following year, at the enthusiastic invitation of senior Tzu Chi volunteer Zhou Sha-han (周莎涵), the couple revisited the Jing Si Abode. Amidst its simple and serene surroundings, Yang learned how Master Cheng Yen led her monastic disciples in adhering to the principle set by Master Bai Zhang (百丈, 749-814), a monk in the Tang Dynasty: “If you don’t work, you don’t eat.” Living by this principle, the nuns at the Abode had done all kinds of handiwork to sustain themselves. Even though they had to work hard to sustain themselves and lived an extremely frugal life, they still committed themselves to philanthropic work and initiated the four Tzu Chi missions of charity, medicine, education, and culture.

Moved by this experience, Yang pledged to translate his inspiration into action and share Master Cheng Yen’s burden of caring for the needy around the world.

He seemed transformed after that, eagerly sharing stories of Tzu Chi with everyone he met. He believed it was his duty as a disciple of Master Cheng Yen to spread the word about Tzu Chi, trusting in karmic connections to determine whether others would be inspired to support the foundation. Undeterred by rejection, he shared about Tzu Chi with increasing confidence and conviction.

His leisure time became almost entirely filled with volunteer work for Tzu Chi. His fishing companions gradually drifted away, and the days of gazing at the sea and quietly observing a bobber’s movements naturally faded from his life.

There were other changes in Yang’s life too. After being addicted to cigarettes for three decades, he began to find them increasingly unpalatable and quit without hesitation. He also transitioned to a vegetarian diet. In 2011, Tzu Chi put on a musical adaptation of the Compassionate Samadhi Water Repentance, a Chinese Buddhist text. Participants were required to observe a vegetarian diet for at least 108 days to help purify their hearts and bodies. Yang resolved to quit eating meat after taking part in the adaptation and embrace vegetarianism to maintain a pure body and mind.

Adding wings

In 2003, he became a documenting volunteer, helping record Tzu Chi events and stories, even though he was a complete novice when it came to computers. Starting with basics like powering on/off and typing in Pinyin, he gradually progressed to editing and finishing video segments on his own. His daughter, Yang Li-yi (楊莉怡), remarked, “Sometimes I see my dad meticulously scrutinizing the screen for a long time to perfect just a few seconds of video. His dedication is truly moving.”

One day in 2013, during a study session of documenting volunteers, attendees discussed using a long pole with a microphone attached for filming activities or interviews, which could result in near-perfect sound quality. Suddenly, Yang thought of his large bag of fishing rods at home. After the study session ended, he hurried back home and opened a long-unused fishing gear bag, finding eight fishing rods inside.

Since dedicating himself to Tzu Chi, he had stopped fishing and had no plans to give away the rods. On his balcony, he wielded a hammer and obliterated five of them, deeply remorseful for taking the lives of many fish in the past. He repurposed the remaining three 18-foot fishing rods for filming purposes, equipping two of them with recording microphones and one with a clip for attaching a mobile phone. Using them, it’s as if a microphone or mobile phone has grown invisible wings—they can glide into every corner, capturing touching moments and documenting the world’s goodness.

On August 5, 2023, documenting volunteers from central Taiwan visited the Jing Si Hall in Taichung for a meeting with Master Cheng Yen. “On the count of five, four, three, two, one…recording!” Yang called out. Under Yang’s guidance, the Master pressed the record button. A converted fishing rod of Yang’s, now adorned with a mobile phone, circled the reception room, capturing video of everyone present. It was a rare opportunity to have their images captured with Master Cheng Yen’s. Everyone wore joyful and warm smiles.

Yang Ma-yun displays ingenuity by attaching a wooden board to a small hand truck and securing a video camera onto it, facilitating easier shooting from a low angle. Wu Chen Mei-yan

By Wang Ming-meng

Translated by Wu Hsiao-ting

Yang Ma-yun, once an avid angler, repurposed his fishing rods into selfie sticks after joining Tzu Chi. Through this adaptation, he enhances the perspectives of the photos and videos he captures for the foundation.

Clang, clang, clang! The heavy iron hammer, typically used for carpentry, struck with resounding blows, filling the air with scattered shards of carbon fiber. Yang Ma-yun (楊媽允), standing on his balcony, felt not a hint of regret as the five premium fishing rods, valued at about 40,000 Taiwanese dollars (US$1,340) in total, were pounded to rubble in just five minutes. Instead, he felt a weight lifted from his shoulders.

Fish’s tears

Yang hails from Xiyu Township, located in Penghu County, an archipelago off Taiwan’s southwestern coast. In his childhood, he enjoyed fishing and playing by the sea with friends, fashioning simple fishing rods from bamboo and using shellfish as bait. His love for fishing persisted as he grew older. He continued fishing after getting married, when he moved to Taichung, central Taiwan.

As an adult, Yang became obsessed with fishing, always looking forward to the end of the workweek. He was often accompanied by his construction industry friends, fostering camaraderie through shared experiences. Weekends and holidays often saw him with fishing companions, equipped with gear and small coolers filled with ice and refreshments, exploring different fishing spots and having a blast.

One of his longest fishing trips began before sunrise and lasted until sunset. He spent nearly the entire day gazing at the sea, his eyes fixed on the bobber, silently anticipating each catch.

His impressive fishing records made him a popular companion among fellow anglers, who often sought his company for fishing outings. Their favorite fishing spot was Taiwan’s northern coast, where, on weekends, it often felt as though there were more anglers lining the shore than fish in the sea. In the wee hours, hundreds of anglers would gather on breakwaters, holding their breath in anticipation of hooking silver-white largehead hairtail. Bathed in moonlight, the sea’s surface shimmered with the greenish glow of floating bobbers, resembling the flicker of fireflies.

Fish don’t have tear ducts, so they can’t cry. But if they could, the flickering lights on the dark sea’s surface might well have been their glistening tears.

In 2012, Tzu Chi volunteers in Taichung held a Buddha Day ceremony at Summer Green Park. Here, Yang Ma-yun films the rehearsal. Yang Rong-shu

A disciple’s responsibility

In 1998, Yang’s wife, Zhuo Yue-jiao (卓月嬌), visited the Jing Si Abode, a Buddhist convent established by Dharma Master Cheng Yen, the founder of Tzu Chi, in Hualien County, eastern Taiwan. Zhuo saw how the monastics there strove to live self-sufficiently through farming and other work rather than relying on offerings. Their efforts deeply touched her. When she returned home, she eagerly shared her experiences with her husband.

The following year, at the enthusiastic invitation of senior Tzu Chi volunteer Zhou Sha-han (周莎涵), the couple revisited the Jing Si Abode. Amidst its simple and serene surroundings, Yang learned how Master Cheng Yen led her monastic disciples in adhering to the principle set by Master Bai Zhang (百丈, 749-814), a monk in the Tang Dynasty: “If you don’t work, you don’t eat.” Living by this principle, the nuns at the Abode had done all kinds of handiwork to sustain themselves. Even though they had to work hard to sustain themselves and lived an extremely frugal life, they still committed themselves to philanthropic work and initiated the four Tzu Chi missions of charity, medicine, education, and culture.

Moved by this experience, Yang pledged to translate his inspiration into action and share Master Cheng Yen’s burden of caring for the needy around the world.

He seemed transformed after that, eagerly sharing stories of Tzu Chi with everyone he met. He believed it was his duty as a disciple of Master Cheng Yen to spread the word about Tzu Chi, trusting in karmic connections to determine whether others would be inspired to support the foundation. Undeterred by rejection, he shared about Tzu Chi with increasing confidence and conviction.

His leisure time became almost entirely filled with volunteer work for Tzu Chi. His fishing companions gradually drifted away, and the days of gazing at the sea and quietly observing a bobber’s movements naturally faded from his life.

There were other changes in Yang’s life too. After being addicted to cigarettes for three decades, he began to find them increasingly unpalatable and quit without hesitation. He also transitioned to a vegetarian diet. In 2011, Tzu Chi put on a musical adaptation of the Compassionate Samadhi Water Repentance, a Chinese Buddhist text. Participants were required to observe a vegetarian diet for at least 108 days to help purify their hearts and bodies. Yang resolved to quit eating meat after taking part in the adaptation and embrace vegetarianism to maintain a pure body and mind.

Adding wings

In 2003, he became a documenting volunteer, helping record Tzu Chi events and stories, even though he was a complete novice when it came to computers. Starting with basics like powering on/off and typing in Pinyin, he gradually progressed to editing and finishing video segments on his own. His daughter, Yang Li-yi (楊莉怡), remarked, “Sometimes I see my dad meticulously scrutinizing the screen for a long time to perfect just a few seconds of video. His dedication is truly moving.”

One day in 2013, during a study session of documenting volunteers, attendees discussed using a long pole with a microphone attached for filming activities or interviews, which could result in near-perfect sound quality. Suddenly, Yang thought of his large bag of fishing rods at home. After the study session ended, he hurried back home and opened a long-unused fishing gear bag, finding eight fishing rods inside.

Since dedicating himself to Tzu Chi, he had stopped fishing and had no plans to give away the rods. On his balcony, he wielded a hammer and obliterated five of them, deeply remorseful for taking the lives of many fish in the past. He repurposed the remaining three 18-foot fishing rods for filming purposes, equipping two of them with recording microphones and one with a clip for attaching a mobile phone. Using them, it’s as if a microphone or mobile phone has grown invisible wings—they can glide into every corner, capturing touching moments and documenting the world’s goodness.

On August 5, 2023, documenting volunteers from central Taiwan visited the Jing Si Hall in Taichung for a meeting with Master Cheng Yen. “On the count of five, four, three, two, one…recording!” Yang called out. Under Yang’s guidance, the Master pressed the record button. A converted fishing rod of Yang’s, now adorned with a mobile phone, circled the reception room, capturing video of everyone present. It was a rare opportunity to have their images captured with Master Cheng Yen’s. Everyone wore joyful and warm smiles.

Yang Ma-yun displays ingenuity by attaching a wooden board to a small hand truck and securing a video camera onto it, facilitating easier shooting from a low angle. Wu Chen Mei-yan

地面が痛まないようにそっと歩こう

編集者の言葉

四月三日に台湾東部の花蓮県沖で発生した強い地震は、地震に慣れている花蓮の人々を恐怖に陥れ、今も苦しめている。当日、静思精舎に到着したネパールの慈済ボランティア一行は、それでも日程を変えず、直ぐ花蓮ボランティアと一緒に災害支援活動に投入した。ボランティアのユニシュさんは、二〇一五年のネパール地震の後、慈済人が遠くカトマンズまで出向いて支援した諸々のことを思い出した。

「あの地震で、私は家も何もかも無くしました。慈済人が福慧ベッドと毛布を持って来てくれたので、床で寝なくて済みました。被災後四、五年間、一家皆、福慧ベッドで寝ていました。そして九年が経った今も、そのベッドは家にあります。地域の人にとってそのベッドは記憶として留まっています。それは、私たちの最も困難な時に、慈済の援助を受けた記念の品なのです」。

福慧ベッドは片手で持ち上げることができるが、彼の心の中ではずっしりとした存在である。人生で最も困難な時に温めてくれたものだからだ。ユニシュさんは目を潤ませた。それは今回花蓮で恩返しできたことをとても幸せだと思ったからだ。

ネパールボランティアに付き添って台湾に来たマレーシアの慈惟(ツーウェイ)さんによれば、余震が続く中でも逃げ出そうとは思わなかった。心霊の故郷で一緒に天地が揺れ動く経験をし、大地の響きを聴いたことで、「歩く時はそっと、地面が痛まないように」という法師のお言葉を思い出した。一歩一歩傷ついたこの世を労るように慎重に足を運ぶのだ。

この二年間、マレーシアとシンガポールの慈済ボランティアは「仏陀の故郷への恩返し」プロジェクトで先行している。ネパールのルンビニとインドのブッダガヤに交替で長期滞在して、苦難の人々を救済すると同時に、善行して福を作るよう導いている。現地に大乗菩薩法を根付かせ、仏陀の理想を実現するのが目標である。

仏陀は当時の古代インドで衆生に説法をしていた。しかし、「衆生の平等」という生命観を持った仏教思想を説いても、十二、十三世紀にはその土地から消失した。インドのカースト制度は、古代バラモン教のヴェーダ思想に基づくものだが、この制度が早い時期に、インドの憲法の父であり、インド佛教復興者でもあるアンベードカル博士によって廃棄が起草されたが、世襲されるカーストの観念は、未だに現地の人々の日常生活に深く根付いている。

「慈済」月刊誌のチームは、取材でインドに滞在していた一カ月間、伝統的な風土と人情を理解すると共に、今まさに起きている変化も目の当たりにした。シンガポールとマレーシアのボランティアは、仏法の理や慈善活動、人文的な情を取り入れ、身分の差によって区別することなく接することで、少しずつ村民に影響を与えている。少なくとも現地ボランティアは、人と人の交流において、カースト制度に左右されないよう取り計っている。衆生への慈悲こそが、今期号で伝えたい二つの重要な報道の主旨である。

(慈済月刊六九〇期より)

編集者の言葉

四月三日に台湾東部の花蓮県沖で発生した強い地震は、地震に慣れている花蓮の人々を恐怖に陥れ、今も苦しめている。当日、静思精舎に到着したネパールの慈済ボランティア一行は、それでも日程を変えず、直ぐ花蓮ボランティアと一緒に災害支援活動に投入した。ボランティアのユニシュさんは、二〇一五年のネパール地震の後、慈済人が遠くカトマンズまで出向いて支援した諸々のことを思い出した。

「あの地震で、私は家も何もかも無くしました。慈済人が福慧ベッドと毛布を持って来てくれたので、床で寝なくて済みました。被災後四、五年間、一家皆、福慧ベッドで寝ていました。そして九年が経った今も、そのベッドは家にあります。地域の人にとってそのベッドは記憶として留まっています。それは、私たちの最も困難な時に、慈済の援助を受けた記念の品なのです」。

福慧ベッドは片手で持ち上げることができるが、彼の心の中ではずっしりとした存在である。人生で最も困難な時に温めてくれたものだからだ。ユニシュさんは目を潤ませた。それは今回花蓮で恩返しできたことをとても幸せだと思ったからだ。

ネパールボランティアに付き添って台湾に来たマレーシアの慈惟(ツーウェイ)さんによれば、余震が続く中でも逃げ出そうとは思わなかった。心霊の故郷で一緒に天地が揺れ動く経験をし、大地の響きを聴いたことで、「歩く時はそっと、地面が痛まないように」という法師のお言葉を思い出した。一歩一歩傷ついたこの世を労るように慎重に足を運ぶのだ。

この二年間、マレーシアとシンガポールの慈済ボランティアは「仏陀の故郷への恩返し」プロジェクトで先行している。ネパールのルンビニとインドのブッダガヤに交替で長期滞在して、苦難の人々を救済すると同時に、善行して福を作るよう導いている。現地に大乗菩薩法を根付かせ、仏陀の理想を実現するのが目標である。

仏陀は当時の古代インドで衆生に説法をしていた。しかし、「衆生の平等」という生命観を持った仏教思想を説いても、十二、十三世紀にはその土地から消失した。インドのカースト制度は、古代バラモン教のヴェーダ思想に基づくものだが、この制度が早い時期に、インドの憲法の父であり、インド佛教復興者でもあるアンベードカル博士によって廃棄が起草されたが、世襲されるカーストの観念は、未だに現地の人々の日常生活に深く根付いている。

「慈済」月刊誌のチームは、取材でインドに滞在していた一カ月間、伝統的な風土と人情を理解すると共に、今まさに起きている変化も目の当たりにした。シンガポールとマレーシアのボランティアは、仏法の理や慈善活動、人文的な情を取り入れ、身分の差によって区別することなく接することで、少しずつ村民に影響を与えている。少なくとも現地ボランティアは、人と人の交流において、カースト制度に左右されないよう取り計っている。衆生への慈悲こそが、今期号で伝えたい二つの重要な報道の主旨である。

(慈済月刊六九〇期より)

能登半島地震 自らの手で見舞金をお年寄りに届ける

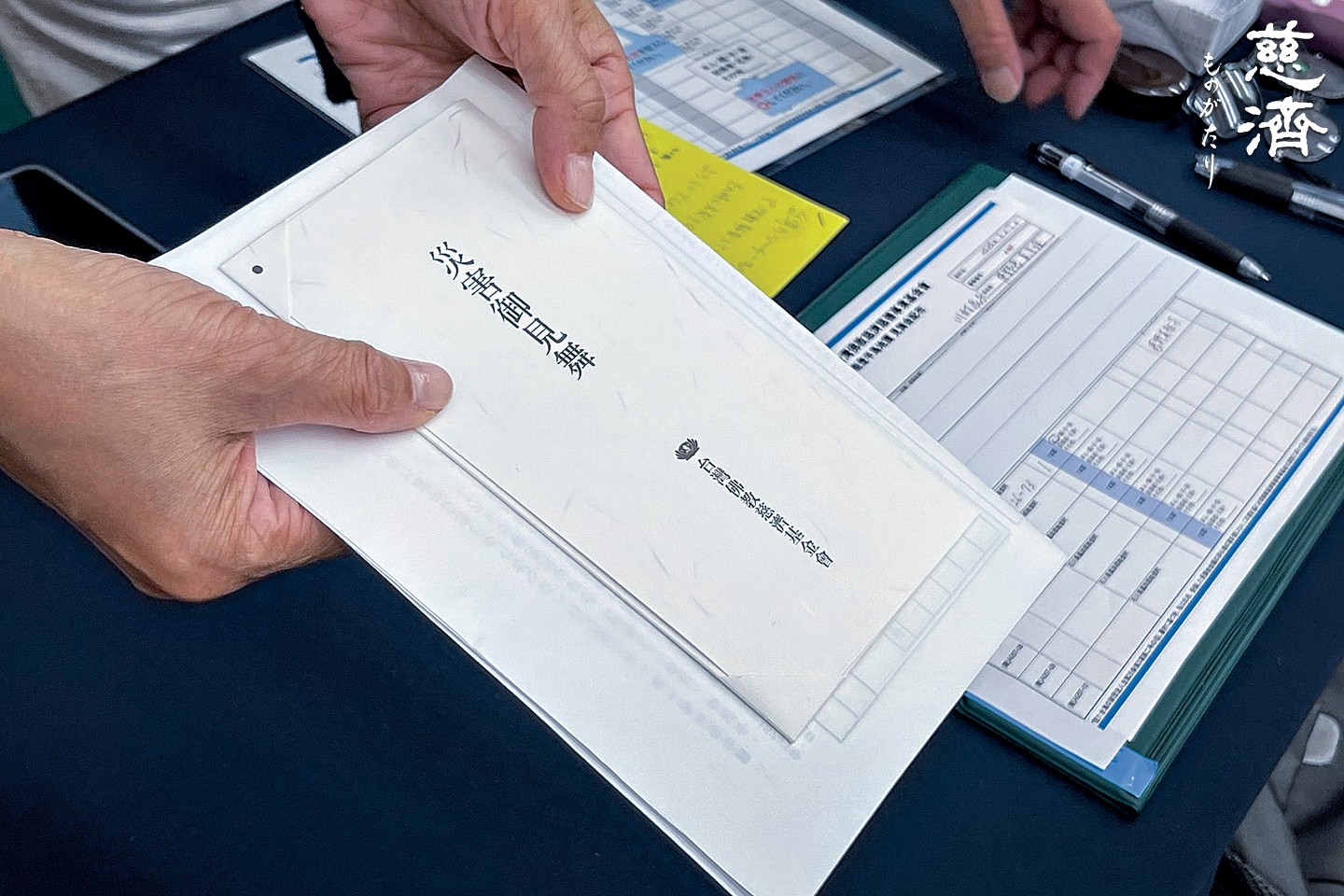

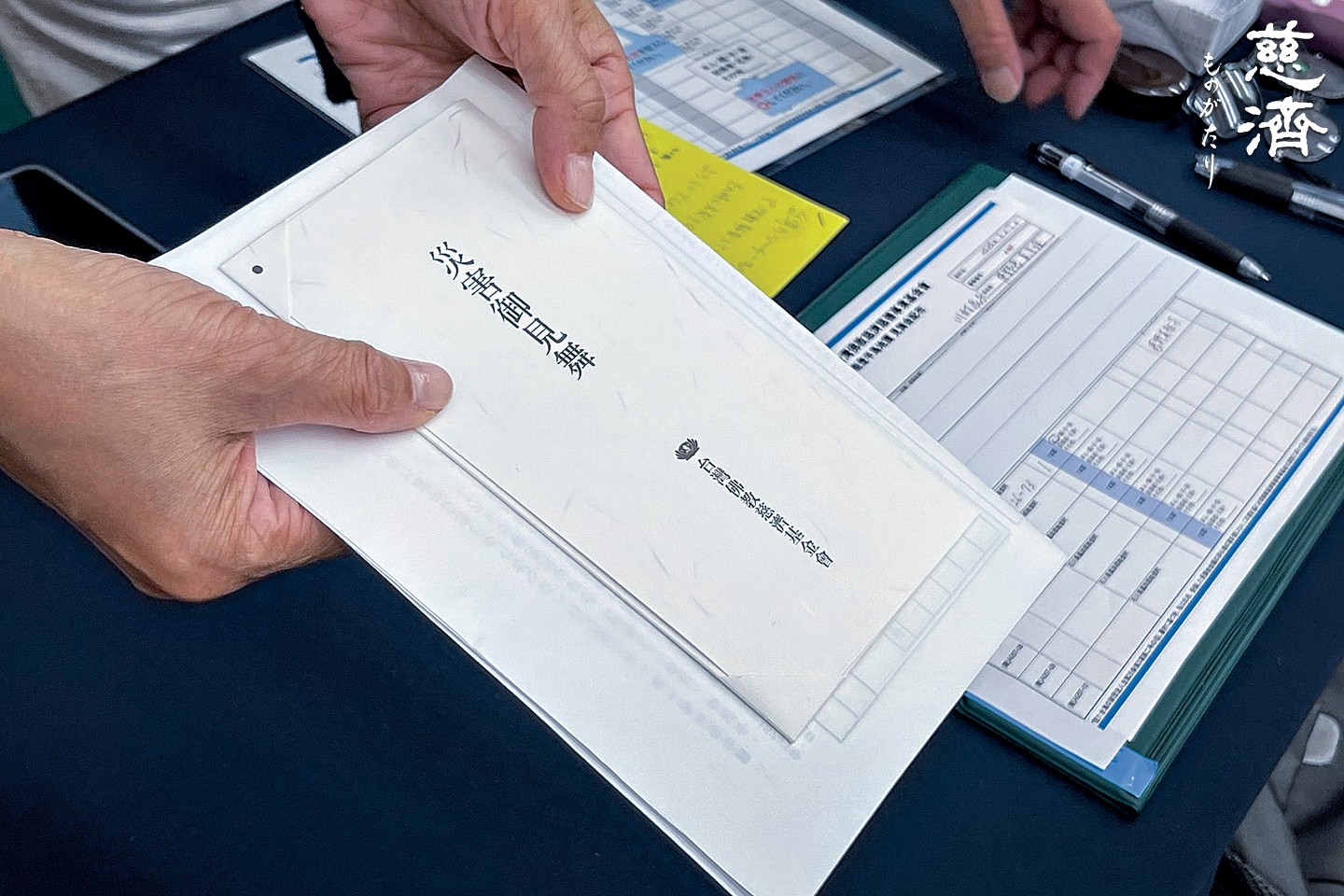

能登半島地震の被災者は、市役所から慈済が「見舞金」を配付する由の通知を受け取ったが、疑念と期待が入り交じった心境にあった。

会場に着いてみると、本当に生活の助けになる現金を受け取ることができた。

驚きと嬉しさに感動する以上に、台湾の慈済が花蓮の地震の後も、依然として彼らを忘れずにいてくれたことに感謝した。

(撮影・王孟専)

今年の元日に発生した石川県能登半島地震は、二百六十人が死亡し、一千二百人が負傷、八万棟の住宅が損壊する被害をもたらした。県全体ではすでに水道が復旧しているが、六月上旬の統計によると、依然として二千八百人が避難所で生活をしている。

地震は能登半島を出入りする唯一の道路を寸断したため、救援活動と建物の解体作業を遅延させた。道路が修復されても、ホテルや旅館が甚大な被害を受けたため、解体業者は泊まる所がない状態にある。また、修復が必要な住宅の数量が膨大なため、解体と再建が遅々として進まないのだ。震源地に最も近い珠洲市を例に挙げると、約四千棟の住宅が全壊し、千人が政府に公費解体を申請しているが、実際に完了したのはわずか数棟である。

今の段階で、住民が最も必要としているのは、現金の補助と再建支援である。県政府と町役場は、「災害義援金」や「生活再建支援金」の支給を公表して、さまざまな補助措置を講じているが、住民は高齢者が多く、申請方法がわからないのだ。更に、甚大被災地はどこも交通が不便な田舎であり、市や町の行政人員が不足しているため、大量の申請案件を一度に処理することができない。

慈済が被災地で見舞金を配付するという情報が住民の耳に入った時、多くの人は半信半疑だった。しかし、五月十七日から十九日にかけて穴水町で初めて千九十一世帯が封筒に入った現金の「見舞金」を受け取った時、住民は信じられない気持ちだった。それは正に恵みの雨だった。

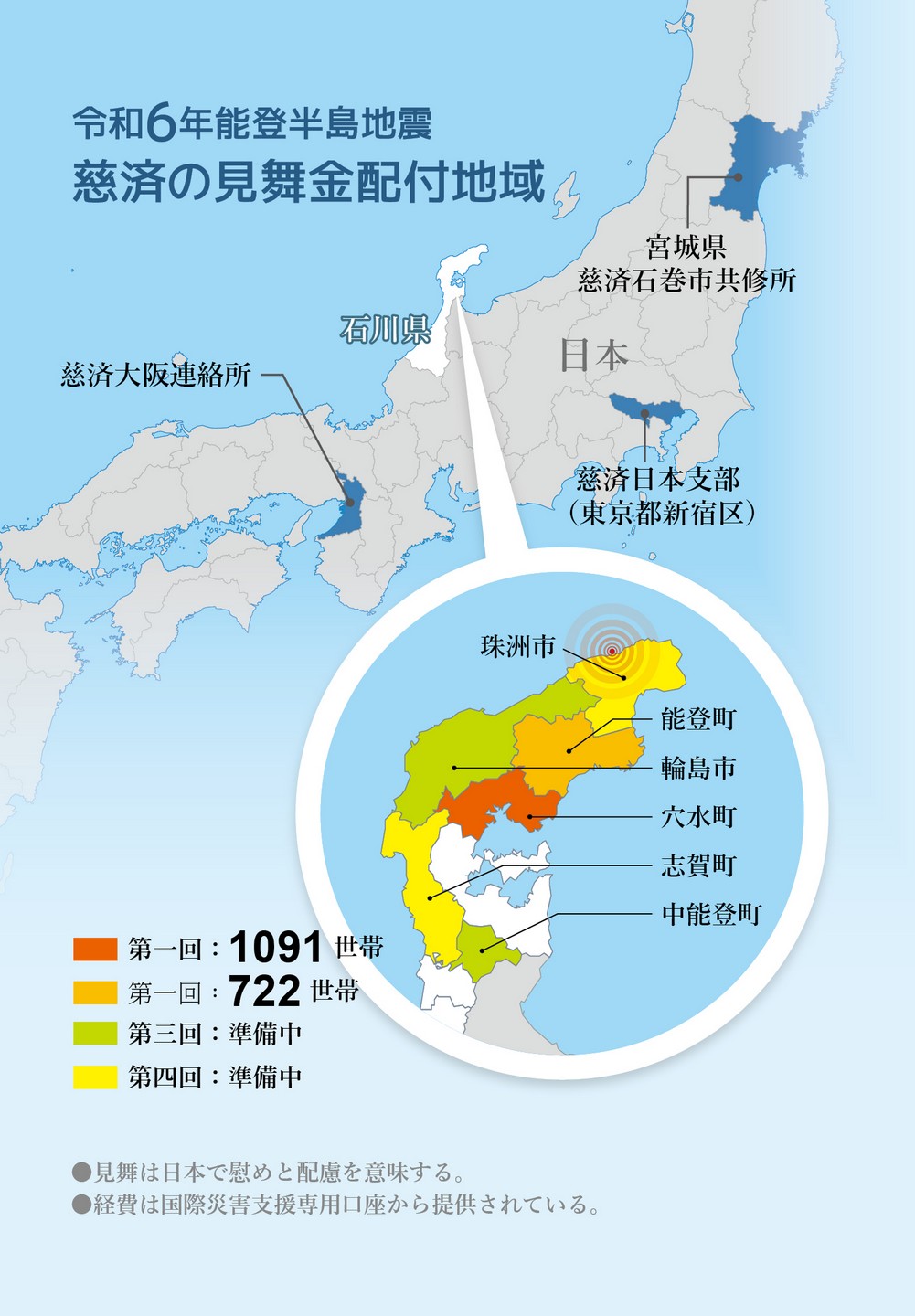

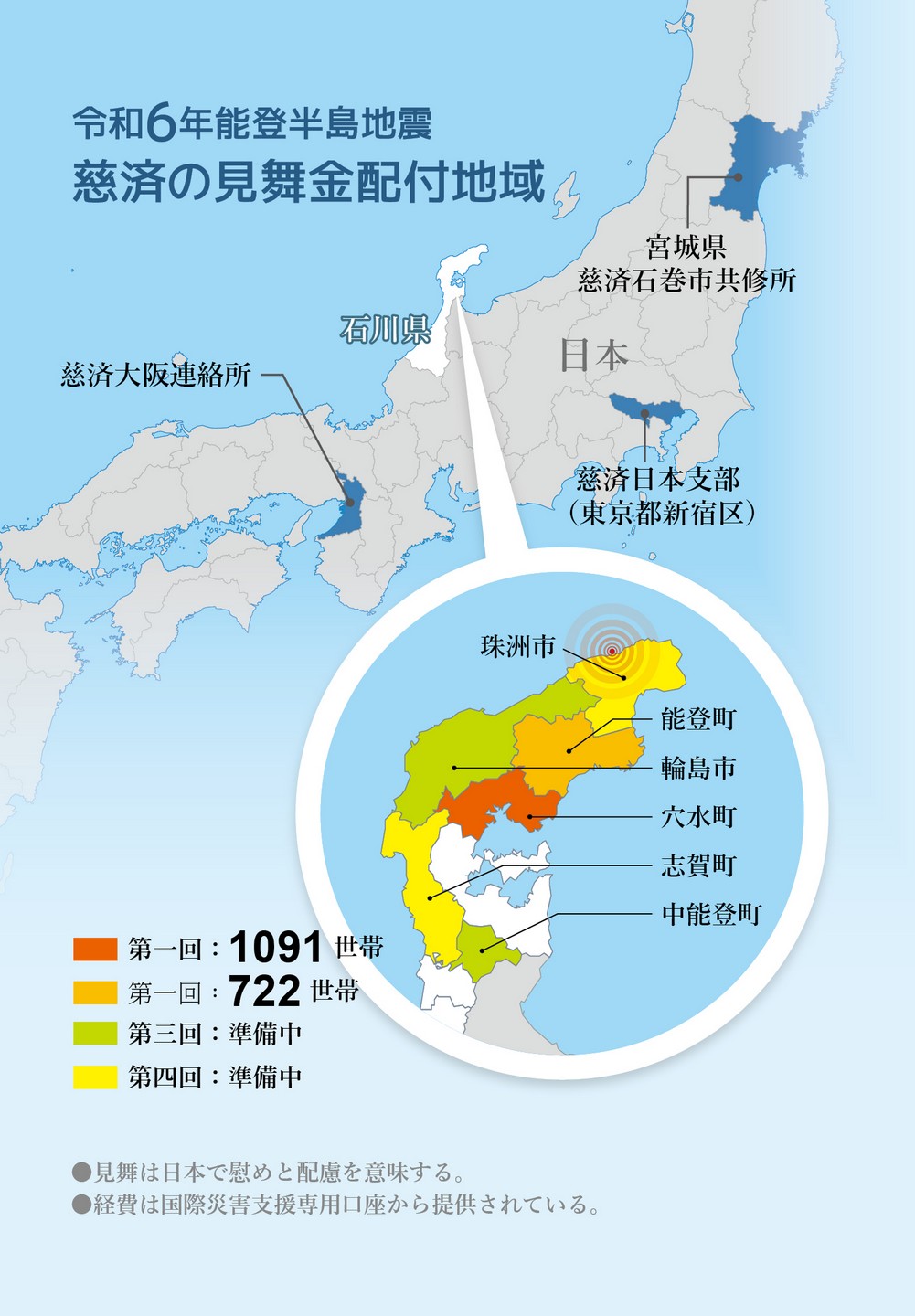

慈済は五月中旬から七月にかけて、穴水、能登、中能登、輪島、志賀、珠洲の六市町で見舞金を順次配付する。対象は地震によって家屋が半壊以上で、且つ六十五歳以上の高齢者がいる世帯である。家族構成の人数に応じて、それぞれ十三万円、十五万円、十七万円が贈られる。

6月9日、ボランティアは台湾の町役場に似た能登町役場で、被災した住民に見舞金を届けて励ました。(撮影・顔婉婷)

地方政府と慈済が協力

第一回の配付は穴水町で完了した。そこは地震発生後、慈済が長期にわたって駐在し、ケアして来た重点地区である。一月十三日から三月三十日まで、二万食余りの温かい食事と飲み物を提供し、延べ七百人以上のボランティアが動員された。

第二回の配付は、六月七日から九日にかけて能登町で行われ、七百二十二世帯が見舞金を受け取った。能登町は北陸でも端の方に位置し、能登半島に囲まれた内海にある。自然との共生を強調した農耕様式が特徴で、世界農業遺産に登録されている。地震の時、震度六強を記録したため、多くの古民家は強い揺れに耐えられなくなり、倒壊したり、傾いたり、崩落したりした。また、地盤が軟弱な所は住宅全体が傾き、液化現象が起きた地域では地盤沈下が続いた。そして、地震によって火災が発生し、複合災害を起こした所もある。

能登町災害対策本部は運営を続けて、十二の避難所が開設され、百人以上が避難生活を送っている。町全体の高齢者人口はほぼ半数を占め、人口密度も低いため、集落同士の距離がかなりある。そのため、慈済と町役場は五つの会場で配付することを決め、高齢者が近くで受け取れるようにした。ボランティアは各会場に早めに行き、配置や整理を行ったが、既に外で待っている住民がいた。

地方政府は、慈済の「重点的、直接、具体的」という災害支援の原則は理解しているが、日本ではプライバシーを重視するため、被災者名簿を提供することはできないと言った。そこで、役場の人が受付で住民の確認を行い、その後に、慈済ボランティアが配付窓口に案内して、罹災証明などの資料を確認することで、見舞金を受け取れるようにした。そして最後に、「住民交流ゾーン」で休憩してもらった。

七十六歳の横地善松さんは、町役場から通知を受け取った時、半信半疑で、先ず会場に行ってみようと思った。彼は会場で、「本当に現金なのですか?振り込みではないのですね?」と何度も確認した。十五万円を受け取ることができたことに驚きを隠せなかった。

「市役所が家を解体してくれるのを待っていますが、何時の事になるやら」と友人の家に身を寄せている横地お爺さんは、「見舞金の出所を聞いて、とても感動しました。このお金は大切に使います。妻や子供たちのために心温まる家を建てます。たとえ平屋建てでも十分です」と言った。子供や孫は年に一度か二度しか帰って来ないが、それでも家族のために家を持ちたいと願っている。

横地お爺さんは続けて、「今日受け取った見舞金の由来を皆に伝え、子供たちも感謝の気持ちを持って社会に還元するよう言います。あなたたちから温かさを感じ、自分の新しい家を建てるための力が湧くと同時に、期待が持てるようになりました」と言った。彼は奥さんと共に優しい笑顔を浮かべながら、「あなたたちの訪問を楽しみにしています」とボランティアに言った。

6月9日、ボランティアは漁村の鵜川を訪れ、公民館に向かう途中で多くの被害を受けた家の前を通った。あたかも時間が元旦の地震後で止まっているように感じられた。(撮影・顔婉婷)

重点的に直接配付する緊急支援の現金

慈済が直接現金を住民に手渡していることについて、多くの人は驚きを隠せず、会場ではしばしば「もったいないことです」という言葉が聞かれた。八十一歳の松田幸子お婆さんは何度も繰り返した。

お婆さんは、八十四歳の夫である松田外紀男さんと娘、そして二十四歳の孫娘と同居している。見舞金を受け取った時、彼女は涙を拭い続けていたが、家までボランティアが同行することを喜んで受け入れた。山林のある小高い丘に位置する日本式建築の家に着くと、ボランティアはお婆さんの家の被災状況がよく分かった。「地震が起きた時、私は台所で調理をしていて、急いで玄関に走ったのですが、揺れが激しくて全く立っていられませんでした。夫は玄関の扉にしっかり掴まってはいましたが、立っていることも外に出ることもできませんでした。私は彼の腰にきつく抱きつき、娘と孫娘はさらに私の腰に抱きつきました。四人が一緒にその場で支え合うのが精一杯で、逃げることができなかったのです!」未だ恐怖が残る幸子お婆さんは、当時を振り返り、天が崩れて地が裂けるように感じ、どこへ逃げればいいのか分からなかったと言った。

家の中の壁は地震で裂けて、一面が崩落し、一家は近くの「小間生公民館」に避難した。被災後、水も電気もなく、女性たちが集まって小さなガスコンロで調理して、何とか十日間を過ごした。一家はとりあえず、金沢市にいる妹の家の近くに借家したが、どうしても自分たちの家に戻りたくて、なんとか整理して住むことにした。

「家が倒れたら、もうだめだ!」と外紀男さんは地震の時、それだけを考えていた。「だから今生きていて、家族も無事なので、本当に幸運です」と語った。幸子お婆さんは、業者に頼んで寝室と台所を修繕してもらったが、二百八十万円余り掛った。全部修繕したら、少なくとも一千万円は必要だろう。「修繕業者からまだ請求して来ませんが、慈済が送って来てくれたこのお金で一部を支払えます。これで私たちの生活も少しは楽になります」。

ボランティアの心温まる慰問と傾聴に、多くの住民は深く感動したと言った。「お金の多い少ないではなく、あなたたちが遠くから来てくれたことで、私たちが得たのは、かけがえのない『温もり』と『情』です!」。

本谷志麻子さんは、6月中旬に能登町公民館の2階にある避難所を離れる予定だ。彼女は、ボランティアが遠方から来て、力を与えてくれたことに感謝した。(撮影・楊景卉)

住む場所があれば、心が安らぐ

本谷志麻子さんは見舞金を受け取った後、ボランティアを避難所に案内した。それは市役所の隣にある「能登町公民館」の二階にあり、彼女は数枚の段ボールで囲った寝室に五カ月余り住んでいた。六月中旬に友人の家に引っ越す予定で、「見舞金をいただきありがとうございます。日用品を買います。来ていただいたことで力をもらいました」と感謝の意を表した。

六十七歳の漁師、山本政広さんもボランティアが彼の仮住まいを見学することに同意した。藤波運動公園に建てられた仮設住宅で、約百二十世帯が住んでいる。一戸当たり約七から八坪の広さで、風呂場とトイレ、そして小さいキッチンには冷蔵庫や電子レンジなどの家電が備わり、小さい長テーブルもある。奥には小部屋が二つあり、一つはリビングとして使っている。山本さんの奥さんは、「今の生活にとても満足しています」と言った。

山本さんの自宅前の道路は三・五メートル陥没し、家は表の方に傾いてしまった。被災後、集会所から移って能登中学で避難生活を送っていたが、五月に仮設住宅に移ってから、ようやく生活が安定してきた。「私はこれまで、懸命に働いて、大勢の子供や孫に囲まれた人生を送って来ましたが、この歳でこんなことに遭うとは思いも寄りませんでした。でも仕方ありません……。三十年間住んでいた家は、見た目には損壊していないのですが、間もなく解体されると思うと、言葉に表せない悲しみがこみ上げてきます」。

仮設住宅には二年間しか住むことができないため、山本さんは政府の災害復興住宅に申請することを検討している。毎月費用はかかるが、年金を受給しているため、負担は軽くなる。慈済から見舞金を受け取れたことについて、彼は「日本では非常に珍しいことで、被災地では初めてです。唯一の現金支援なので、とても驚くと共に、嬉しく思っています」と言った。

七十歳の上野実喜雄さんは、金沢市からバスで故郷に戻り、見舞金を受け取った。彼は地震当時のことを振り返り、二度の強い揺れの後、町役場から津波が来るというアナウンスを聞いて、急いで避難するよう住民に呼びかけた。しかし、自分の家が変形して傾き、ドアが開かなくなった。細身の上野さんの奥さんは、どこにそんな力があったのか、素手で強化ガラスの窓を割り、二人は脱出することができた。裸足のまま、近くの寺まで歩いて靴を二足借り、更に高台に避難した。

家主は高齢者への賃貸を渋り、彼らは息子の名義で金沢に家を借りることにした。かつて魚貝類の取引をしていた上野さんは、今は失業中だが、見舞金を使って家電を買うつもりだ。「遠くから来てくれたボランティアに感謝しています。見舞金を配付するだけでなく、熱いお茶やお菓子を出して頂いた上に、平安のお守りまでいただきました。こんなに多くの支援を受けられるとは思ってもいませんでした……」と言いながら、奥さんは涙を抑えきれなかった。

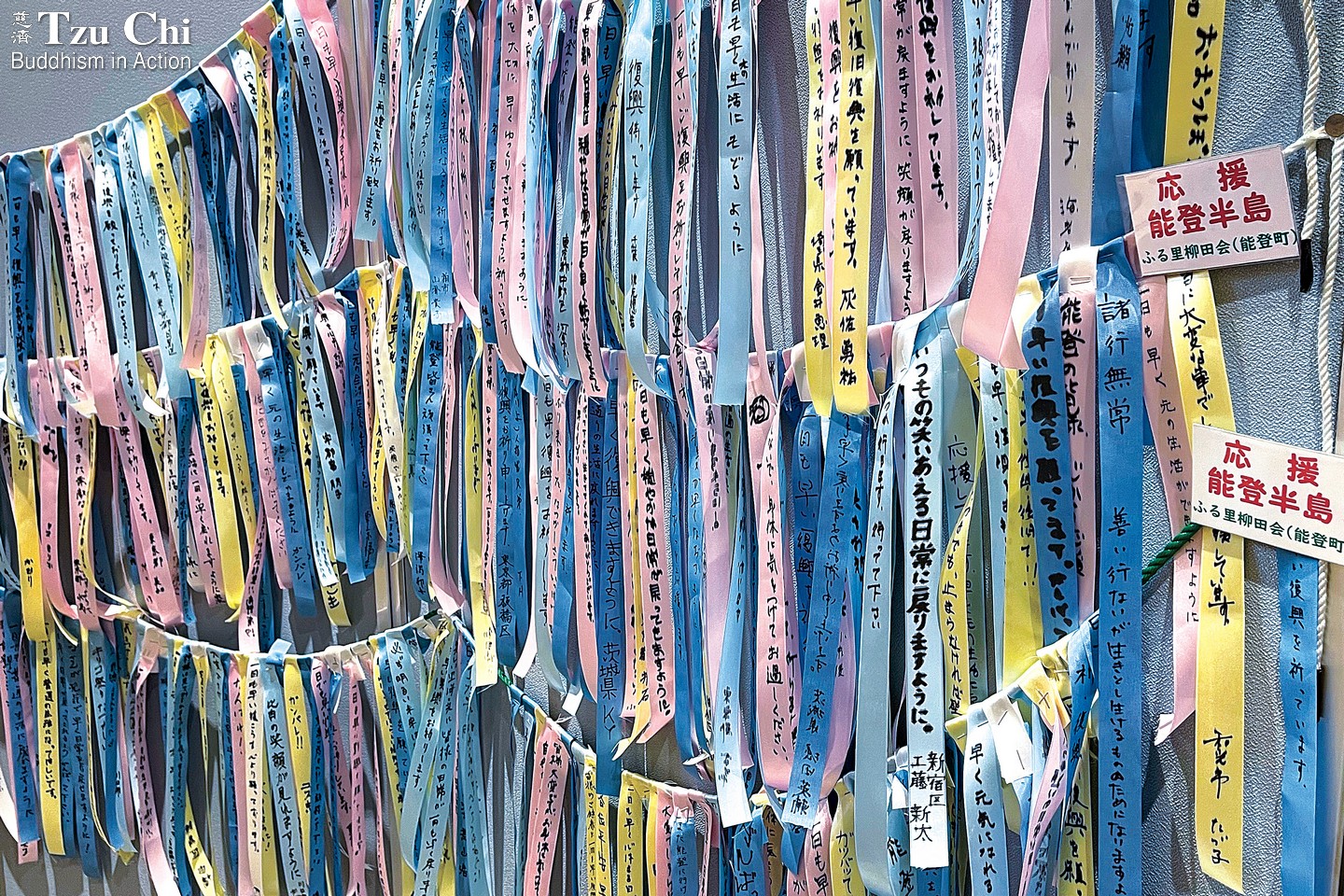

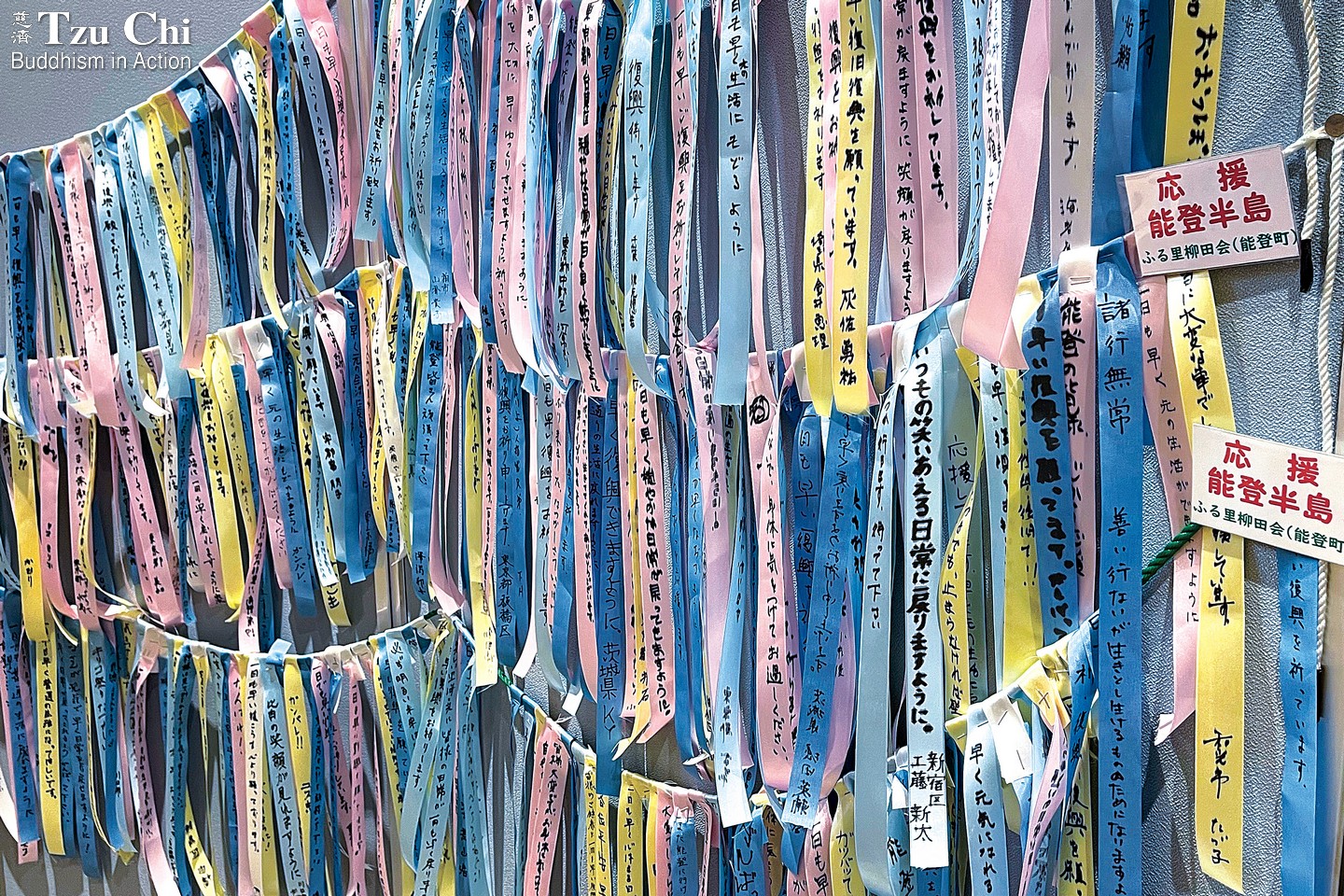

能登町役場の入口には、各地から寄せられたカードや布がいっぱい掲げられ、励ましのメッセージが書かれてあった。(撮影・顔婉婷)

能登の人々は情に厚く、誠実で親切

この半年間、ボランティアは被災地を行き来して、関係者と配付活動の打ち合わせを行った。證厳法師に災害状況を報告した時、日本の住宅被害の「全壊、半壊、準半壊、一部損壊」などの程度に応じて異なる金額の支援を計画してはどうか、と提案した。法師は「全壊でも半壊でも壊れたことに変わりはありません。区別すべきではありません。また、被災者が六十四歳で、六十五歳に少し足りないからといって助けないでいいのでしょうか?目の前に困っている人がいれば、個別案件にして助けるべきです」と指摘した。

慈済日本支部の執行長である許麗香師姐によると、東京と大阪からのボランティアが交替で被災地に赴いて炊き出しをすると共に、「仕事を与えて支援に代える」活動に参加した地元の人々を食事に招待した。慈済カフェは今でも穴水総合病院で運営されており、今回の見舞金配付に繋がっている。東京に戻るたびに、地元の人々の感動の涙が脳裏に焼き付いているそうだ。

「老いた農夫は、『銀行の預金が底をつき、農地の水も尽きてしまいました。数日前に川から二トンの水を運んで来ましたが、これで野菜が芽を出すかどうかは分かりません。このような大金を受け取ることができ、正に恵みの雨です』と言いました。私たちは、能登には美しい山と水があるだけでなく、厚い人情という美徳もあることを目にしました。地元の人々は涙を流しながら、『四月三日に花蓮で地震が起き、台湾自身も被災しているにも関わらず、私たちの最も必要な時に自ら支援に来てくれたことに感動せずにはおれません』と話してくれました」。

六月中旬、輪島市の公式メディアが、慈済が月末に見舞金を配付することを伝えると、問い合わせの電話が慈済日本支部に殺到した。東京や大阪のボランティアが誠意をもって輪島に向かうと聞いた、遠くに避難している住民は、何としてでも戻って受け取りたい、と感動しながら言った。次から次にかかって来る電話に対応しながら、ボランティアたちは、「世界中の愛と祝福を地元の人々に伝えることができて、とても嬉しいです!」と感想を述べた。(資料提供・顔婉婷、呂瑩瑩、黄静蘊、王孟専、呉恵珍、朱秀蓮)

(慈済月刊六九二期より)

能登半島地震の被災者は、市役所から慈済が「見舞金」を配付する由の通知を受け取ったが、疑念と期待が入り交じった心境にあった。

会場に着いてみると、本当に生活の助けになる現金を受け取ることができた。

驚きと嬉しさに感動する以上に、台湾の慈済が花蓮の地震の後も、依然として彼らを忘れずにいてくれたことに感謝した。

(撮影・王孟専)

今年の元日に発生した石川県能登半島地震は、二百六十人が死亡し、一千二百人が負傷、八万棟の住宅が損壊する被害をもたらした。県全体ではすでに水道が復旧しているが、六月上旬の統計によると、依然として二千八百人が避難所で生活をしている。

地震は能登半島を出入りする唯一の道路を寸断したため、救援活動と建物の解体作業を遅延させた。道路が修復されても、ホテルや旅館が甚大な被害を受けたため、解体業者は泊まる所がない状態にある。また、修復が必要な住宅の数量が膨大なため、解体と再建が遅々として進まないのだ。震源地に最も近い珠洲市を例に挙げると、約四千棟の住宅が全壊し、千人が政府に公費解体を申請しているが、実際に完了したのはわずか数棟である。

今の段階で、住民が最も必要としているのは、現金の補助と再建支援である。県政府と町役場は、「災害義援金」や「生活再建支援金」の支給を公表して、さまざまな補助措置を講じているが、住民は高齢者が多く、申請方法がわからないのだ。更に、甚大被災地はどこも交通が不便な田舎であり、市や町の行政人員が不足しているため、大量の申請案件を一度に処理することができない。

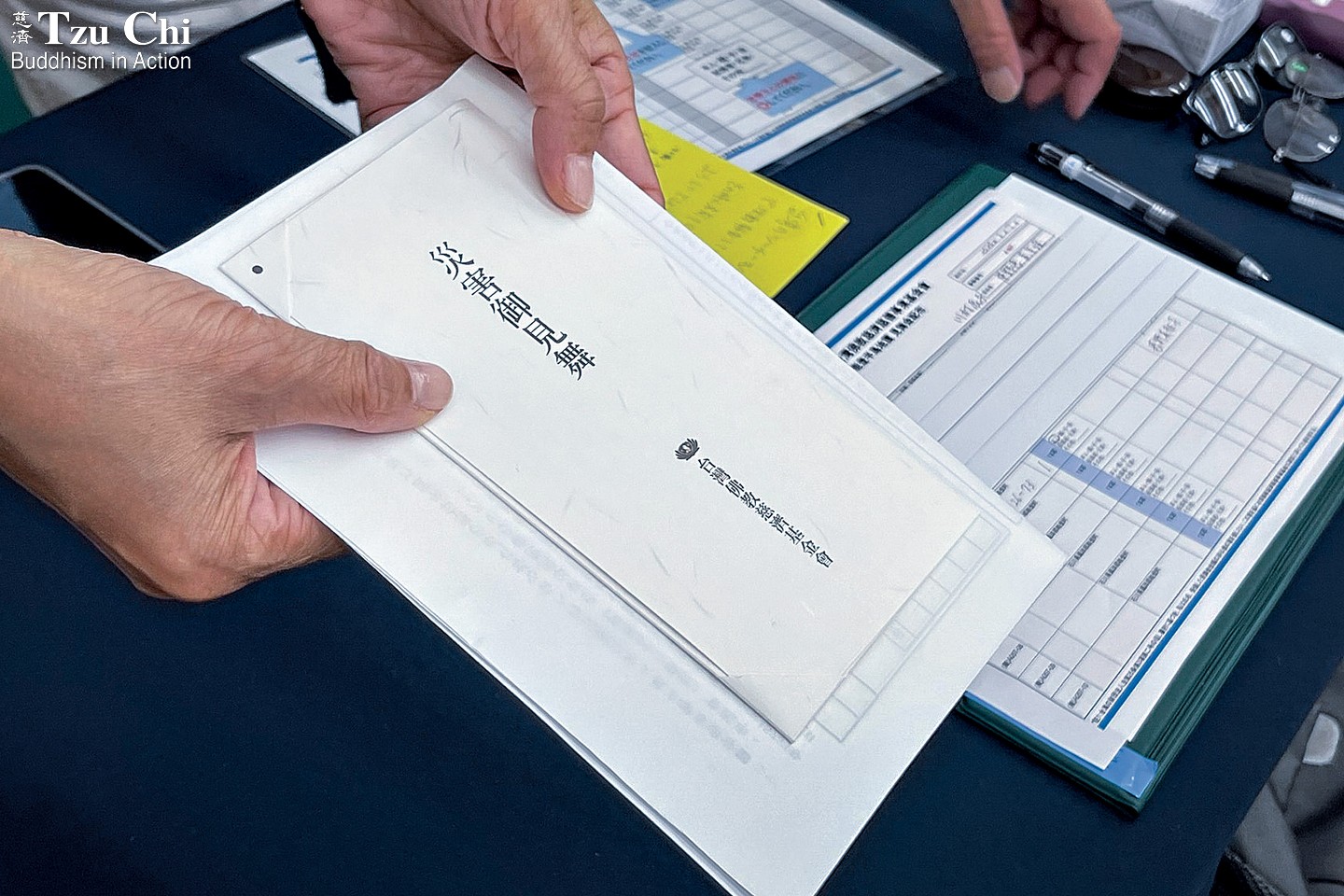

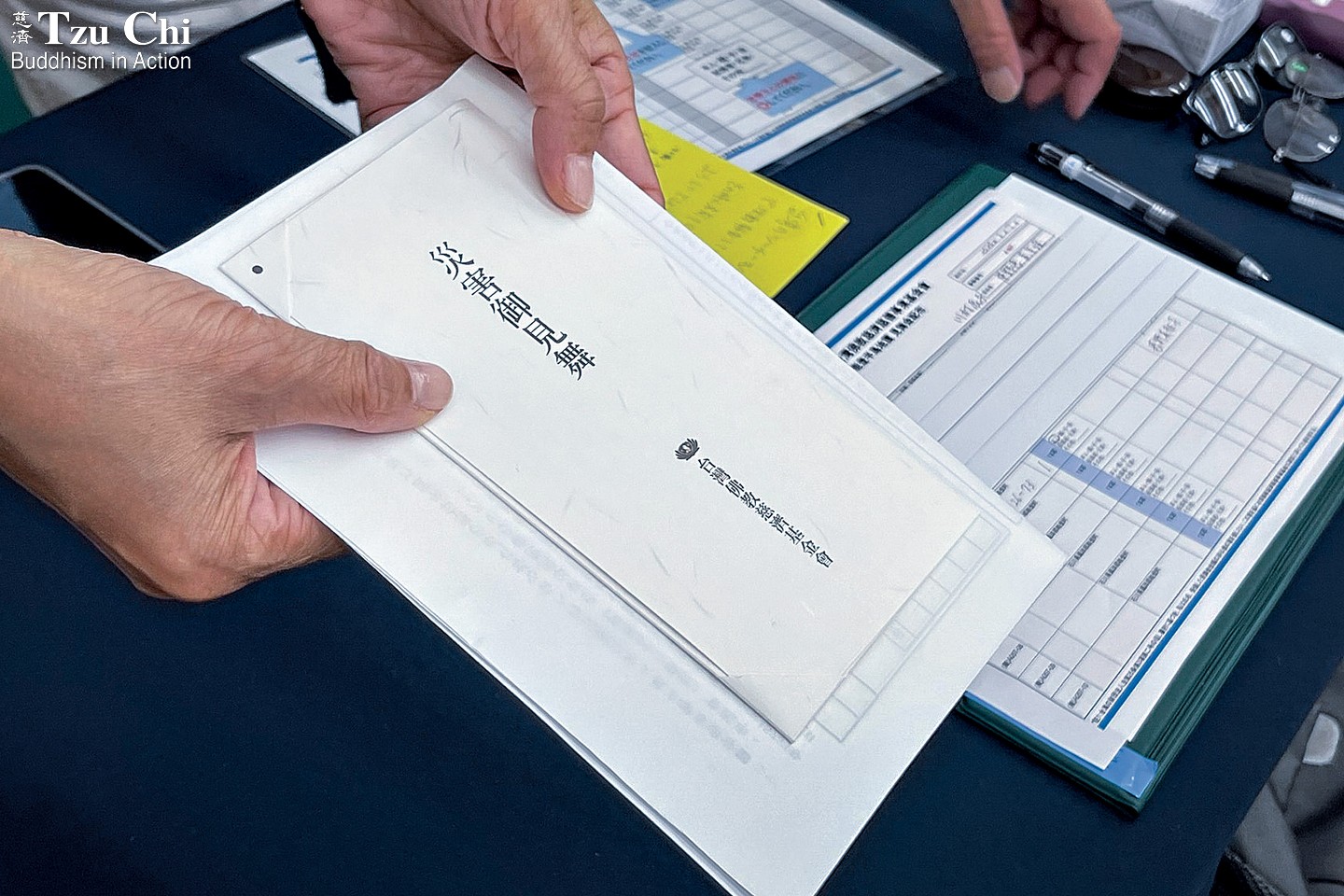

慈済が被災地で見舞金を配付するという情報が住民の耳に入った時、多くの人は半信半疑だった。しかし、五月十七日から十九日にかけて穴水町で初めて千九十一世帯が封筒に入った現金の「見舞金」を受け取った時、住民は信じられない気持ちだった。それは正に恵みの雨だった。

慈済は五月中旬から七月にかけて、穴水、能登、中能登、輪島、志賀、珠洲の六市町で見舞金を順次配付する。対象は地震によって家屋が半壊以上で、且つ六十五歳以上の高齢者がいる世帯である。家族構成の人数に応じて、それぞれ十三万円、十五万円、十七万円が贈られる。

6月9日、ボランティアは台湾の町役場に似た能登町役場で、被災した住民に見舞金を届けて励ました。(撮影・顔婉婷)

地方政府と慈済が協力

第一回の配付は穴水町で完了した。そこは地震発生後、慈済が長期にわたって駐在し、ケアして来た重点地区である。一月十三日から三月三十日まで、二万食余りの温かい食事と飲み物を提供し、延べ七百人以上のボランティアが動員された。

第二回の配付は、六月七日から九日にかけて能登町で行われ、七百二十二世帯が見舞金を受け取った。能登町は北陸でも端の方に位置し、能登半島に囲まれた内海にある。自然との共生を強調した農耕様式が特徴で、世界農業遺産に登録されている。地震の時、震度六強を記録したため、多くの古民家は強い揺れに耐えられなくなり、倒壊したり、傾いたり、崩落したりした。また、地盤が軟弱な所は住宅全体が傾き、液化現象が起きた地域では地盤沈下が続いた。そして、地震によって火災が発生し、複合災害を起こした所もある。

能登町災害対策本部は運営を続けて、十二の避難所が開設され、百人以上が避難生活を送っている。町全体の高齢者人口はほぼ半数を占め、人口密度も低いため、集落同士の距離がかなりある。そのため、慈済と町役場は五つの会場で配付することを決め、高齢者が近くで受け取れるようにした。ボランティアは各会場に早めに行き、配置や整理を行ったが、既に外で待っている住民がいた。

地方政府は、慈済の「重点的、直接、具体的」という災害支援の原則は理解しているが、日本ではプライバシーを重視するため、被災者名簿を提供することはできないと言った。そこで、役場の人が受付で住民の確認を行い、その後に、慈済ボランティアが配付窓口に案内して、罹災証明などの資料を確認することで、見舞金を受け取れるようにした。そして最後に、「住民交流ゾーン」で休憩してもらった。

七十六歳の横地善松さんは、町役場から通知を受け取った時、半信半疑で、先ず会場に行ってみようと思った。彼は会場で、「本当に現金なのですか?振り込みではないのですね?」と何度も確認した。十五万円を受け取ることができたことに驚きを隠せなかった。

「市役所が家を解体してくれるのを待っていますが、何時の事になるやら」と友人の家に身を寄せている横地お爺さんは、「見舞金の出所を聞いて、とても感動しました。このお金は大切に使います。妻や子供たちのために心温まる家を建てます。たとえ平屋建てでも十分です」と言った。子供や孫は年に一度か二度しか帰って来ないが、それでも家族のために家を持ちたいと願っている。

横地お爺さんは続けて、「今日受け取った見舞金の由来を皆に伝え、子供たちも感謝の気持ちを持って社会に還元するよう言います。あなたたちから温かさを感じ、自分の新しい家を建てるための力が湧くと同時に、期待が持てるようになりました」と言った。彼は奥さんと共に優しい笑顔を浮かべながら、「あなたたちの訪問を楽しみにしています」とボランティアに言った。

6月9日、ボランティアは漁村の鵜川を訪れ、公民館に向かう途中で多くの被害を受けた家の前を通った。あたかも時間が元旦の地震後で止まっているように感じられた。(撮影・顔婉婷)

重点的に直接配付する緊急支援の現金

慈済が直接現金を住民に手渡していることについて、多くの人は驚きを隠せず、会場ではしばしば「もったいないことです」という言葉が聞かれた。八十一歳の松田幸子お婆さんは何度も繰り返した。

お婆さんは、八十四歳の夫である松田外紀男さんと娘、そして二十四歳の孫娘と同居している。見舞金を受け取った時、彼女は涙を拭い続けていたが、家までボランティアが同行することを喜んで受け入れた。山林のある小高い丘に位置する日本式建築の家に着くと、ボランティアはお婆さんの家の被災状況がよく分かった。「地震が起きた時、私は台所で調理をしていて、急いで玄関に走ったのですが、揺れが激しくて全く立っていられませんでした。夫は玄関の扉にしっかり掴まってはいましたが、立っていることも外に出ることもできませんでした。私は彼の腰にきつく抱きつき、娘と孫娘はさらに私の腰に抱きつきました。四人が一緒にその場で支え合うのが精一杯で、逃げることができなかったのです!」未だ恐怖が残る幸子お婆さんは、当時を振り返り、天が崩れて地が裂けるように感じ、どこへ逃げればいいのか分からなかったと言った。

家の中の壁は地震で裂けて、一面が崩落し、一家は近くの「小間生公民館」に避難した。被災後、水も電気もなく、女性たちが集まって小さなガスコンロで調理して、何とか十日間を過ごした。一家はとりあえず、金沢市にいる妹の家の近くに借家したが、どうしても自分たちの家に戻りたくて、なんとか整理して住むことにした。

「家が倒れたら、もうだめだ!」と外紀男さんは地震の時、それだけを考えていた。「だから今生きていて、家族も無事なので、本当に幸運です」と語った。幸子お婆さんは、業者に頼んで寝室と台所を修繕してもらったが、二百八十万円余り掛った。全部修繕したら、少なくとも一千万円は必要だろう。「修繕業者からまだ請求して来ませんが、慈済が送って来てくれたこのお金で一部を支払えます。これで私たちの生活も少しは楽になります」。

ボランティアの心温まる慰問と傾聴に、多くの住民は深く感動したと言った。「お金の多い少ないではなく、あなたたちが遠くから来てくれたことで、私たちが得たのは、かけがえのない『温もり』と『情』です!」。

本谷志麻子さんは、6月中旬に能登町公民館の2階にある避難所を離れる予定だ。彼女は、ボランティアが遠方から来て、力を与えてくれたことに感謝した。(撮影・楊景卉)

住む場所があれば、心が安らぐ

本谷志麻子さんは見舞金を受け取った後、ボランティアを避難所に案内した。それは市役所の隣にある「能登町公民館」の二階にあり、彼女は数枚の段ボールで囲った寝室に五カ月余り住んでいた。六月中旬に友人の家に引っ越す予定で、「見舞金をいただきありがとうございます。日用品を買います。来ていただいたことで力をもらいました」と感謝の意を表した。

六十七歳の漁師、山本政広さんもボランティアが彼の仮住まいを見学することに同意した。藤波運動公園に建てられた仮設住宅で、約百二十世帯が住んでいる。一戸当たり約七から八坪の広さで、風呂場とトイレ、そして小さいキッチンには冷蔵庫や電子レンジなどの家電が備わり、小さい長テーブルもある。奥には小部屋が二つあり、一つはリビングとして使っている。山本さんの奥さんは、「今の生活にとても満足しています」と言った。

山本さんの自宅前の道路は三・五メートル陥没し、家は表の方に傾いてしまった。被災後、集会所から移って能登中学で避難生活を送っていたが、五月に仮設住宅に移ってから、ようやく生活が安定してきた。「私はこれまで、懸命に働いて、大勢の子供や孫に囲まれた人生を送って来ましたが、この歳でこんなことに遭うとは思いも寄りませんでした。でも仕方ありません……。三十年間住んでいた家は、見た目には損壊していないのですが、間もなく解体されると思うと、言葉に表せない悲しみがこみ上げてきます」。

仮設住宅には二年間しか住むことができないため、山本さんは政府の災害復興住宅に申請することを検討している。毎月費用はかかるが、年金を受給しているため、負担は軽くなる。慈済から見舞金を受け取れたことについて、彼は「日本では非常に珍しいことで、被災地では初めてです。唯一の現金支援なので、とても驚くと共に、嬉しく思っています」と言った。

七十歳の上野実喜雄さんは、金沢市からバスで故郷に戻り、見舞金を受け取った。彼は地震当時のことを振り返り、二度の強い揺れの後、町役場から津波が来るというアナウンスを聞いて、急いで避難するよう住民に呼びかけた。しかし、自分の家が変形して傾き、ドアが開かなくなった。細身の上野さんの奥さんは、どこにそんな力があったのか、素手で強化ガラスの窓を割り、二人は脱出することができた。裸足のまま、近くの寺まで歩いて靴を二足借り、更に高台に避難した。

家主は高齢者への賃貸を渋り、彼らは息子の名義で金沢に家を借りることにした。かつて魚貝類の取引をしていた上野さんは、今は失業中だが、見舞金を使って家電を買うつもりだ。「遠くから来てくれたボランティアに感謝しています。見舞金を配付するだけでなく、熱いお茶やお菓子を出して頂いた上に、平安のお守りまでいただきました。こんなに多くの支援を受けられるとは思ってもいませんでした……」と言いながら、奥さんは涙を抑えきれなかった。

能登町役場の入口には、各地から寄せられたカードや布がいっぱい掲げられ、励ましのメッセージが書かれてあった。(撮影・顔婉婷)

能登の人々は情に厚く、誠実で親切

この半年間、ボランティアは被災地を行き来して、関係者と配付活動の打ち合わせを行った。證厳法師に災害状況を報告した時、日本の住宅被害の「全壊、半壊、準半壊、一部損壊」などの程度に応じて異なる金額の支援を計画してはどうか、と提案した。法師は「全壊でも半壊でも壊れたことに変わりはありません。区別すべきではありません。また、被災者が六十四歳で、六十五歳に少し足りないからといって助けないでいいのでしょうか?目の前に困っている人がいれば、個別案件にして助けるべきです」と指摘した。

慈済日本支部の執行長である許麗香師姐によると、東京と大阪からのボランティアが交替で被災地に赴いて炊き出しをすると共に、「仕事を与えて支援に代える」活動に参加した地元の人々を食事に招待した。慈済カフェは今でも穴水総合病院で運営されており、今回の見舞金配付に繋がっている。東京に戻るたびに、地元の人々の感動の涙が脳裏に焼き付いているそうだ。

「老いた農夫は、『銀行の預金が底をつき、農地の水も尽きてしまいました。数日前に川から二トンの水を運んで来ましたが、これで野菜が芽を出すかどうかは分かりません。このような大金を受け取ることができ、正に恵みの雨です』と言いました。私たちは、能登には美しい山と水があるだけでなく、厚い人情という美徳もあることを目にしました。地元の人々は涙を流しながら、『四月三日に花蓮で地震が起き、台湾自身も被災しているにも関わらず、私たちの最も必要な時に自ら支援に来てくれたことに感動せずにはおれません』と話してくれました」。

六月中旬、輪島市の公式メディアが、慈済が月末に見舞金を配付することを伝えると、問い合わせの電話が慈済日本支部に殺到した。東京や大阪のボランティアが誠意をもって輪島に向かうと聞いた、遠くに避難している住民は、何としてでも戻って受け取りたい、と感動しながら言った。次から次にかかって来る電話に対応しながら、ボランティアたちは、「世界中の愛と祝福を地元の人々に伝えることができて、とても嬉しいです!」と感想を述べた。(資料提供・顔婉婷、呂瑩瑩、黄静蘊、王孟専、呉恵珍、朱秀蓮)

(慈済月刊六九二期より)

Continued Support for Japan’s Quake Victims

Text and photo by Tzu Chi documenting volunteers

Edited and translated by Wu Hsiao-ting

Tzu Chi’s direct cash aid brings hope and warmth to earthquake victims on Japan’s Noto Peninsula.

Photo by Wang Meng-zhuan

On New Year’s Day, an earthquake struck Japan’s Noto Peninsula, in Ishikawa Prefecture, resulting in 260 deaths, 1,200 injuries, and damage to 80,000 houses. The quake also destroyed the only road into and out of the Noto Peninsula, complicating rescue and demolition efforts.

Even after the road was repaired, the severe damage to hotels left demolition crews nowhere to stay and slowed efforts to rebuild. For example, the earthquake destroyed about 4,000 houses in Suzu City, the area closest to the epicenter. Although a thousand people there applied for government-funded demolition, only a few cases had been completed months after the quake.

Given the extent of the damage, residents were in need of cash assistance for reconstruction. Prefectural and town offices announced emergency support funds with various subsidy measures, but many residents, especially the elderly, were unsure how to apply. Insufficient administrative manpower in the disaster area further delayed the application process.

Amidst this uncertainty, it was announced that Tzu Chi would be distributing cash aid. Many residents were hopeful but skeptical. However, from May 17 to 19, representatives from 1,091 households in the town of Anamizu received financial assistance from the foundation. They could not believe such timely help!

Tzu Chi began distributing cash assistance in mid-May and will continue into July. The aid is directed at families with homes meeting two criteria: being over 50 percent damaged and having elderly residents aged 65 and above. The targeted areas include the towns and cities of Anamizu, Noto, Nakanoto, Wajima, Shika, and Suzu. Depending on their size, households have received or will receive amounts of 130,000, 150,000, or 170,000 Japanese yen (US$825-$1,080).

Tzu Chi volunteers and a quake survivor bow to each other during a cash aid distribution at the Noto town office in Japan’s Ishikawa Prefecture on June 9.

Collaboration for relief

The first round of distributions took place in Anamizu, where Tzu Chi focused its care after the earthquake. Between January 13 and March 30, volunteers from Tokyo and Osaka, along with residents participating in a Tzu Chi work relief program, provided over 20,000 servings of hot meals and drinks in the town.

The second set of cash aid distributions were held from June 7 to 9 in the town of Noto, where 722 households received aid. Noto is renowned for its farming practices that harmonize with nature, which have earned recognition as a Globally Important Agricultural Heritage System. The earthquake on New Year’s Day caused many old houses in the town to collapse, tilt, or crumble. Some houses began to sink when the soil liquefied in the shaking.

Twelve evacuation centers with over a hundred residents were still open in the town when Tzu Chi held its distributions there. Nearly half of the town’s population is elderly and settlements are dispersed, so Tzu Chi and the local government organized five distributions to ensure easy access for the elderly. Though volunteers arrived early at each location to set up, they were never early enough to beat the residents already waiting for them.

Although privacy is highly regarded in Japanese culture, the local government understood Tzu Chi’s principle of direct disaster relief, which aims to distribute aid personally, without intermediaries. Although the local government wouldn’t provide a list of affected households to Tzu Chi, they arranged for civil servants to verify the identities of recipients in the reception area of the distribution venue. Then, Tzu Chi volunteers guided recipients to service counters to gather and verify additional information necessary for them to receive assistance. Finally, recipients were directed to the interaction area where they could rest and converse with volunteers.

Seventy-six-year-old Yoshimatsu Yokochi said he was initially skeptical when he received a notification letter from the town office about Tzu Chi’s distribution, but he decided to check it out in person. Once he was there, he kept asking, “Are we really getting cash? Not a bank transfer?” He just couldn’t believe he would be receiving 150,000 yen in cash.

He and his wife were staying at a friend’s home at the time. “We’re still waiting for the city office to demolish our house,” he said, “but we don’t know when that will happen.” He was very touched when he learned the source of Tzu Chi’s relief funds and said he would cherish the money and put it towards building a new home for his wife and children. Although his children and grandchildren only visit once or twice a year, he still hoped to provide them with a home for their stays.

He added that he would tell his children about Tzu Chi’s help to encourage them to pay the love forward. “I feel your warmth,” he said, “and now I feel motivated and hopeful about building a new home.” He and his wife smiled kindly at the volunteers receiving them, saying, “We look forward to having you visit our new home.”

A volunteer passes a damaged house in the fishing village of Ukawa, Noto, on his way to distribute aid on June 9. Yan Wan-ting

Priceless warmth and love

Many people were amazed that Tzu Chi volunteers personally delivered cash to them. Exclamations like, “We can’t express how thankful we are!” were heard repeatedly at the distributions. Eighty-one-year-old Sachiko Matsuda said this several times herself.

Mrs. Matsuda lives with her 84-year-old husband, Sodetosio, and two other family members. She wiped away tears after receiving aid from Tzu Chi and agreed to let volunteers accompany her home to see how the quake had affected their house. The group arrived at a traditional Japanese-style house on a slope.

“I was cooking in the kitchen when the earthquake hit,” Mrs. Matsuda told the visitors. “I quickly rushed to the entrance of our home, but the shaking was so severe I couldn’t stay on my feet.” Her husband was holding on to the door, unable to stand up or get out. She hugged his waist, and their daughter and granddaughter hugged hers. The four of them clung together, unable to make it out of their house. Still haunted by the memory, she remembered feeling like the sky was falling. Mr. Matsuda, on the other hand, said that his only thought during the earthquake was that the house was about to collapse. He felt hopeless. “Now that I’m still alive and my family is safe,” he said, “I consider us really lucky.”

Because a wall of their home collapsed during the tremor, the whole family had to move to a nearby shelter. There was no running water or electricity in the aftermath of the disaster, so local women gathered and worked together to cook with small gas stoves. After living like this for ten days, the family rented a house near a relative’s home in Kanazawa, the capital of Ishikawa Prefecture. They lived there for some time but wanted to return to their own home, so they tidied it up the best they could and settled back in.

Mrs. Matsuda told the volunteers that it had cost them more than 2.8 million yen (US$17,760) to have a contractor repair a bedroom and kitchen. She added that it would cost at least ten million yen to have everything repaired. “The contractor hasn’t invoiced us yet,” she said. “The money from Tzu Chi will help cover the repair costs, which will make our lives a little easier.”

Many residents expressed deep gratitude for the volunteers’ comforting words and attentive listening. One resident said, “It’s not about the money you provided, but the fact that you came from afar to help us.” She was referring to the volunteers who had traveled all the way from Taiwan. “The warmth and love we received from you is priceless!”

Honya Shimako, pictured here at her evacuation center, thanks Tzu Chi volunteers for traveling from afar to help them, giving them strength. Jessica Yang

Short-term shelter solutions

After receiving her cash aid, Shimako Motoya led a small group of Tzu Chi volunteers back to the evacuation center where she was staying, right next to the town office. She had been sheltering there for over five months, using cardboard to section off a bedroom. She planned to move to a friend’s house in mid-June. “Thank you for the cash aid,” she said to the volunteers. “I’ll use it to buy daily necessities. But more importantly, thank you for coming. Your presence gives me strength.”

Sixty-seven-year-old fisherman Masahiro Yamamoto also agreed to show volunteers his temporary housing, which was built in Fujinami Sports Park. The housing complex there accommodated about 120 families. Each unit was approximately 25 square meters (265 square feet) and featured a bathroom with separate wet and dry areas, a small kitchen equipped with household appliances, including a refrigerator and a microwave, and two small rooms, one of which served as a living room. Mrs. Yamamoto expressed satisfaction with their current living conditions.

The road in front of the Yamamotos’ old residence sank 3.5 meters (11 feet), causing the house to tilt forward. The couple stayed at two evacuation centers before moving into their current temporary housing in May, which brought more stability to their lives. “I worked hard my entire life to support my family and am now blessed with many children and grandchildren,” Yamamoto said. “I never expected to face something like this at my age, but there’s nothing we can do.” He mentioned that their 30-year-old house—which looked undamaged apart from its tilt—would soon be dismantled. The thought filled him with indescribable sadness.

Their temporary housing was only available for two years, so Yamamoto thought about applying for government disaster recovery housing. Despite being retired, he could use his pension to help cover the monthly fee. He mentioned that Tzu Chi was the first and only charity to distribute cash in the disaster area and that he felt honored to receive the help.

Seventy-year-old Mikio Ueno made a special trip from Kanazawa by bus to receive the cash aid. He recalled how the town office broadcast a warning of an impending tsunami after two strong shocks on January 1, urging residents to evacuate. He and his wife quickly prepared to flee. However, their house had deformed and tilted, trapping them inside. Despite her frailness, Mrs. Ueno managed to break a reinforced glass window with her bare hands, allowing them to escape. Barefoot, they hurried to a nearby temple to borrow two pairs of shoes before fleeing to higher ground.

Afterwards, they rented a house in Kanazawa. The landlord was reluctant to rent to older people, so they rented under their son’s name. Mr. Ueno used to work in the fish trade but was now unemployed. He said he planned to use Tzu Chi’s aid to buy household appliances.

“Thank you for coming from afar to help us,” said Mrs. Ueno. “Not only did you distribute cash to us, but you also served us hot tea and snacks, and gave us good-luck ornaments. I never expected to receive so much.” She choked up with emotion as she spoke.

At the entrance of the Noto town office, numerous cards and ribbons from various locations adorn the area, bearing messages of encouragement and blessings for the local earthquake victims. Yan Wan-ting

Heartfelt appreciation in Noto

Tzu Chi volunteers repeatedly visited the disaster area for six months following the earthquake. They assessed the damage, provided hot meals, discussed aid distribution plans with relevant agencies, and then followed up with distributions.

Xu Li-xiang (許麗香), CEO of Tzu Chi Japan, shared that her mind was filled with images of the local residents’ gratitude each time she returned to Tokyo from the disaster area. She recounted the story of an older farmer who said, “My bank account is running out of money, and I’m worried about the water source for my fields. A few days ago, I brought two tons of water from a river, but I’m unsure if it will be enough for my vegetables to sprout. Receiving such a large amount of money from you is truly like timely rain.”

Xu complimented the Noto Peninsula not only for its beautiful scenery but also for its people and their spirit of deep gratitude. “Residents kept shedding tears, saying Taiwan was similarly affected after the strong earthquake in Hualien on April 3. How could they not be moved, knowing Tzu Chi volunteers still came personally to help them?”

In mid-June, Wajima city announced that Tzu Chi would distribute cash aid at the end of the month, leading to a flood of inquiries to Tzu Chi Japan. Evacuees sheltering out of town were moved and expressed their determination to return home to receive the aid. Despite the endless calls, volunteers said that the chance to express the love from around the world to the quake survivors was truly a great joy.

Text and photo by Tzu Chi documenting volunteers

Edited and translated by Wu Hsiao-ting

Tzu Chi’s direct cash aid brings hope and warmth to earthquake victims on Japan’s Noto Peninsula.

Photo by Wang Meng-zhuan

On New Year’s Day, an earthquake struck Japan’s Noto Peninsula, in Ishikawa Prefecture, resulting in 260 deaths, 1,200 injuries, and damage to 80,000 houses. The quake also destroyed the only road into and out of the Noto Peninsula, complicating rescue and demolition efforts.

Even after the road was repaired, the severe damage to hotels left demolition crews nowhere to stay and slowed efforts to rebuild. For example, the earthquake destroyed about 4,000 houses in Suzu City, the area closest to the epicenter. Although a thousand people there applied for government-funded demolition, only a few cases had been completed months after the quake.

Given the extent of the damage, residents were in need of cash assistance for reconstruction. Prefectural and town offices announced emergency support funds with various subsidy measures, but many residents, especially the elderly, were unsure how to apply. Insufficient administrative manpower in the disaster area further delayed the application process.

Amidst this uncertainty, it was announced that Tzu Chi would be distributing cash aid. Many residents were hopeful but skeptical. However, from May 17 to 19, representatives from 1,091 households in the town of Anamizu received financial assistance from the foundation. They could not believe such timely help!

Tzu Chi began distributing cash assistance in mid-May and will continue into July. The aid is directed at families with homes meeting two criteria: being over 50 percent damaged and having elderly residents aged 65 and above. The targeted areas include the towns and cities of Anamizu, Noto, Nakanoto, Wajima, Shika, and Suzu. Depending on their size, households have received or will receive amounts of 130,000, 150,000, or 170,000 Japanese yen (US$825-$1,080).

Tzu Chi volunteers and a quake survivor bow to each other during a cash aid distribution at the Noto town office in Japan’s Ishikawa Prefecture on June 9.

Collaboration for relief

The first round of distributions took place in Anamizu, where Tzu Chi focused its care after the earthquake. Between January 13 and March 30, volunteers from Tokyo and Osaka, along with residents participating in a Tzu Chi work relief program, provided over 20,000 servings of hot meals and drinks in the town.

The second set of cash aid distributions were held from June 7 to 9 in the town of Noto, where 722 households received aid. Noto is renowned for its farming practices that harmonize with nature, which have earned recognition as a Globally Important Agricultural Heritage System. The earthquake on New Year’s Day caused many old houses in the town to collapse, tilt, or crumble. Some houses began to sink when the soil liquefied in the shaking.

Twelve evacuation centers with over a hundred residents were still open in the town when Tzu Chi held its distributions there. Nearly half of the town’s population is elderly and settlements are dispersed, so Tzu Chi and the local government organized five distributions to ensure easy access for the elderly. Though volunteers arrived early at each location to set up, they were never early enough to beat the residents already waiting for them.

Although privacy is highly regarded in Japanese culture, the local government understood Tzu Chi’s principle of direct disaster relief, which aims to distribute aid personally, without intermediaries. Although the local government wouldn’t provide a list of affected households to Tzu Chi, they arranged for civil servants to verify the identities of recipients in the reception area of the distribution venue. Then, Tzu Chi volunteers guided recipients to service counters to gather and verify additional information necessary for them to receive assistance. Finally, recipients were directed to the interaction area where they could rest and converse with volunteers.

Seventy-six-year-old Yoshimatsu Yokochi said he was initially skeptical when he received a notification letter from the town office about Tzu Chi’s distribution, but he decided to check it out in person. Once he was there, he kept asking, “Are we really getting cash? Not a bank transfer?” He just couldn’t believe he would be receiving 150,000 yen in cash.

He and his wife were staying at a friend’s home at the time. “We’re still waiting for the city office to demolish our house,” he said, “but we don’t know when that will happen.” He was very touched when he learned the source of Tzu Chi’s relief funds and said he would cherish the money and put it towards building a new home for his wife and children. Although his children and grandchildren only visit once or twice a year, he still hoped to provide them with a home for their stays.

He added that he would tell his children about Tzu Chi’s help to encourage them to pay the love forward. “I feel your warmth,” he said, “and now I feel motivated and hopeful about building a new home.” He and his wife smiled kindly at the volunteers receiving them, saying, “We look forward to having you visit our new home.”

A volunteer passes a damaged house in the fishing village of Ukawa, Noto, on his way to distribute aid on June 9. Yan Wan-ting

Priceless warmth and love

Many people were amazed that Tzu Chi volunteers personally delivered cash to them. Exclamations like, “We can’t express how thankful we are!” were heard repeatedly at the distributions. Eighty-one-year-old Sachiko Matsuda said this several times herself.

Mrs. Matsuda lives with her 84-year-old husband, Sodetosio, and two other family members. She wiped away tears after receiving aid from Tzu Chi and agreed to let volunteers accompany her home to see how the quake had affected their house. The group arrived at a traditional Japanese-style house on a slope.

“I was cooking in the kitchen when the earthquake hit,” Mrs. Matsuda told the visitors. “I quickly rushed to the entrance of our home, but the shaking was so severe I couldn’t stay on my feet.” Her husband was holding on to the door, unable to stand up or get out. She hugged his waist, and their daughter and granddaughter hugged hers. The four of them clung together, unable to make it out of their house. Still haunted by the memory, she remembered feeling like the sky was falling. Mr. Matsuda, on the other hand, said that his only thought during the earthquake was that the house was about to collapse. He felt hopeless. “Now that I’m still alive and my family is safe,” he said, “I consider us really lucky.”

Because a wall of their home collapsed during the tremor, the whole family had to move to a nearby shelter. There was no running water or electricity in the aftermath of the disaster, so local women gathered and worked together to cook with small gas stoves. After living like this for ten days, the family rented a house near a relative’s home in Kanazawa, the capital of Ishikawa Prefecture. They lived there for some time but wanted to return to their own home, so they tidied it up the best they could and settled back in.

Mrs. Matsuda told the volunteers that it had cost them more than 2.8 million yen (US$17,760) to have a contractor repair a bedroom and kitchen. She added that it would cost at least ten million yen to have everything repaired. “The contractor hasn’t invoiced us yet,” she said. “The money from Tzu Chi will help cover the repair costs, which will make our lives a little easier.”

Many residents expressed deep gratitude for the volunteers’ comforting words and attentive listening. One resident said, “It’s not about the money you provided, but the fact that you came from afar to help us.” She was referring to the volunteers who had traveled all the way from Taiwan. “The warmth and love we received from you is priceless!”

Honya Shimako, pictured here at her evacuation center, thanks Tzu Chi volunteers for traveling from afar to help them, giving them strength. Jessica Yang

Short-term shelter solutions

After receiving her cash aid, Shimako Motoya led a small group of Tzu Chi volunteers back to the evacuation center where she was staying, right next to the town office. She had been sheltering there for over five months, using cardboard to section off a bedroom. She planned to move to a friend’s house in mid-June. “Thank you for the cash aid,” she said to the volunteers. “I’ll use it to buy daily necessities. But more importantly, thank you for coming. Your presence gives me strength.”

Sixty-seven-year-old fisherman Masahiro Yamamoto also agreed to show volunteers his temporary housing, which was built in Fujinami Sports Park. The housing complex there accommodated about 120 families. Each unit was approximately 25 square meters (265 square feet) and featured a bathroom with separate wet and dry areas, a small kitchen equipped with household appliances, including a refrigerator and a microwave, and two small rooms, one of which served as a living room. Mrs. Yamamoto expressed satisfaction with their current living conditions.

The road in front of the Yamamotos’ old residence sank 3.5 meters (11 feet), causing the house to tilt forward. The couple stayed at two evacuation centers before moving into their current temporary housing in May, which brought more stability to their lives. “I worked hard my entire life to support my family and am now blessed with many children and grandchildren,” Yamamoto said. “I never expected to face something like this at my age, but there’s nothing we can do.” He mentioned that their 30-year-old house—which looked undamaged apart from its tilt—would soon be dismantled. The thought filled him with indescribable sadness.

Their temporary housing was only available for two years, so Yamamoto thought about applying for government disaster recovery housing. Despite being retired, he could use his pension to help cover the monthly fee. He mentioned that Tzu Chi was the first and only charity to distribute cash in the disaster area and that he felt honored to receive the help.

Seventy-year-old Mikio Ueno made a special trip from Kanazawa by bus to receive the cash aid. He recalled how the town office broadcast a warning of an impending tsunami after two strong shocks on January 1, urging residents to evacuate. He and his wife quickly prepared to flee. However, their house had deformed and tilted, trapping them inside. Despite her frailness, Mrs. Ueno managed to break a reinforced glass window with her bare hands, allowing them to escape. Barefoot, they hurried to a nearby temple to borrow two pairs of shoes before fleeing to higher ground.

Afterwards, they rented a house in Kanazawa. The landlord was reluctant to rent to older people, so they rented under their son’s name. Mr. Ueno used to work in the fish trade but was now unemployed. He said he planned to use Tzu Chi’s aid to buy household appliances.

“Thank you for coming from afar to help us,” said Mrs. Ueno. “Not only did you distribute cash to us, but you also served us hot tea and snacks, and gave us good-luck ornaments. I never expected to receive so much.” She choked up with emotion as she spoke.

At the entrance of the Noto town office, numerous cards and ribbons from various locations adorn the area, bearing messages of encouragement and blessings for the local earthquake victims. Yan Wan-ting

Heartfelt appreciation in Noto

Tzu Chi volunteers repeatedly visited the disaster area for six months following the earthquake. They assessed the damage, provided hot meals, discussed aid distribution plans with relevant agencies, and then followed up with distributions.

Xu Li-xiang (許麗香), CEO of Tzu Chi Japan, shared that her mind was filled with images of the local residents’ gratitude each time she returned to Tokyo from the disaster area. She recounted the story of an older farmer who said, “My bank account is running out of money, and I’m worried about the water source for my fields. A few days ago, I brought two tons of water from a river, but I’m unsure if it will be enough for my vegetables to sprout. Receiving such a large amount of money from you is truly like timely rain.”

Xu complimented the Noto Peninsula not only for its beautiful scenery but also for its people and their spirit of deep gratitude. “Residents kept shedding tears, saying Taiwan was similarly affected after the strong earthquake in Hualien on April 3. How could they not be moved, knowing Tzu Chi volunteers still came personally to help them?”

In mid-June, Wajima city announced that Tzu Chi would distribute cash aid at the end of the month, leading to a flood of inquiries to Tzu Chi Japan. Evacuees sheltering out of town were moved and expressed their determination to return home to receive the aid. Despite the endless calls, volunteers said that the chance to express the love from around the world to the quake survivors was truly a great joy.

Hands-On Agricultural Experiences

By Yeh Tzu-hao

Abridged and translated by Wu Hsiao-ting

Photo by Yan Lin-zhao

From planting seeds and tending crops to harvesting, transporting, and cooking, the journey of food from the field to our dining table is far from simple.

“Look, earthworms!” an elementary student exclaimed while pulling up some amaranth plants from the soil, alerting his peers to be mindful of the creatures below.

The elementary division of Tainan Tzu Chi Senior High School maintains a small kitchen garden on campus, where parent gardening volunteers and students participating in the U.S.-Taiwan Eco-Campus Partnership Program grow various vegetables and fruits. Every Friday morning, these adults and children put on cotton gloves, grab hoes and shovels, and get to work cultivating the garden together.

They were harvesting amaranth on this particular Friday morning. Pesticides are eschewed in the garden, but not even holes in the leaves caused by cabbage worms could dampen the enthusiasm of the children as they proudly held up some of their amaranth harvest, showcasing their accomplishment. Due to campus food safety requirements, the garden’s produce cannot be added to school lunches. Instead, any harvested vegetables are taken home by volunteers and students, distributed to staff, or given as gifts to visiting guests.

Once the harvesting was complete, the gardening volunteers showed the children how to prepare the soil for planting new vegetables. A white-haired volunteer then guided the students in evenly dispersing water spinach seeds on the vegetable bed where the amaranth had been, reminding them to be gentle when covering the seeds with soil. She mentioned that in just three days, they would be able to see the seeds sprouting.

The farming activities began at eight o’clock and concluded in about half an hour. During this time, the students completed tasks such as harvesting, soil preparation, seed sowing, fertilizing, and watering. Despite the sweat on their faces and the dirt on their hands and legs, everyone enjoyed the process. It was mid-April; the vegetables would be ripe for harvest by late May or early June.

“This kind of agricultural labor is hard to experience nowadays unless parents specifically take their children to the fields on weekends or holidays,” said Xu Rong-sheng (徐榮勝), chairman of Tainan Tzu Chi Senior High School’s Parents’ Association. “But here at the Tzu Chi school, we have the opportunity to experience farming right on campus.” Xu, who was volunteering in the garden that day, shared that he became a gardening volunteer when his son was in second grade at the school. Though his son is now in eighth grade, he is still leading elementary students to cultivate vegetables.

“Growing vegetables isn’t easy,” Xu added. “From germination to maturity, it requires a lot of care. When children understand how vegetables are grown, they will better appreciate what’s in their bowls and be more likely to finish their food.”

Students in the elementary division of Tainan Tzu Chi Senior High School harvest amaranth plants on campus. Participating in farming activities helps children develop a connection with the earth and nurtures a sense of gratitude for their daily food.

Food and agricultural education

Many parents struggle to persuade their children to eat vegetables and are often met with resistance, such as tightly closed mouths or tears. A psychological experiment at Yale University showed that toddlers aged eight to 18 months instinctively avoided real plants when presented with both man-made and natural objects. This avoidance is possibly an evolved survival mechanism to avoid potential poisoning or harm from thorns or fuzz. Understanding such instinctive behaviors highlights the importance of teaching children about a balanced diet and the origins of their food. Effective food and agricultural education is essential in shaping healthy eating habits and fostering a deeper appreciation for food.

Taiwan has been making efforts to promote food and agricultural education, as evidenced by the recent passing of the Food and Agricultural Education Act in April 2022. This legislation outlines six key principles: supporting local agriculture; promoting balanced diets; reducing food waste; preserving and innovating food culture; strengthening the link between food and agriculture; and advocating for sustainable local production and consumption. Encouraged by the Ministry of Education, many teachers and students visit produce farms, fisheries, livestock farms, and food processing plants to learn more about food production. Many schools even grow vegetables and fruits on campus or raise chickens to lay eggs, providing students with hands-on learning opportunities right at school.

The kitchen garden at the Tainan Tzu Chi school mentioned earlier was created even before the Food and Agricultural Education Act was passed. Yen Hsiu-wen, the director of academic affairs in the elementary division of the school, views the garden as a “landscape dining table,” allowing children to cultivate and witness the growth of fruits and vegetables they regularly consume. “Through observing, recording, and reflecting on how a tiny seed grows into a mature plant,” she explained, “children come to understand that cultivating vegetables is no simple task. They also learn that food goes through additional steps, such as transportation and cooking, before it ends up on our dining tables. Appreciating the effort involved helps develop a deeper sense of gratitude for our food.”

Successful food and agricultural education should foster a sense of connection with and care for food, the land, and all those involved in the food production process. Professor Chiu Yie-ju (邱奕儒), the director of the Master’s Program in Sustainability and Disaster Management at Tzu Chi University, in eastern Taiwan, pointed out that one of humanity’s most severe problems is the lack of understanding about how our food grows from the land, resulting in a loss of connection with the earth. When people reconnect with the land, they naturally gain security and develop inner confidence.

“Food and agricultural education should start as early as possible,” Chiu asserted. Understanding how food is grown and harvested helps cultivate much-needed virtues, including an appreciation for food, mindfulness of reducing waste, and respect for the environment.

By Yeh Tzu-hao

Abridged and translated by Wu Hsiao-ting

Photo by Yan Lin-zhao

From planting seeds and tending crops to harvesting, transporting, and cooking, the journey of food from the field to our dining table is far from simple.

“Look, earthworms!” an elementary student exclaimed while pulling up some amaranth plants from the soil, alerting his peers to be mindful of the creatures below.

The elementary division of Tainan Tzu Chi Senior High School maintains a small kitchen garden on campus, where parent gardening volunteers and students participating in the U.S.-Taiwan Eco-Campus Partnership Program grow various vegetables and fruits. Every Friday morning, these adults and children put on cotton gloves, grab hoes and shovels, and get to work cultivating the garden together.

They were harvesting amaranth on this particular Friday morning. Pesticides are eschewed in the garden, but not even holes in the leaves caused by cabbage worms could dampen the enthusiasm of the children as they proudly held up some of their amaranth harvest, showcasing their accomplishment. Due to campus food safety requirements, the garden’s produce cannot be added to school lunches. Instead, any harvested vegetables are taken home by volunteers and students, distributed to staff, or given as gifts to visiting guests.

Once the harvesting was complete, the gardening volunteers showed the children how to prepare the soil for planting new vegetables. A white-haired volunteer then guided the students in evenly dispersing water spinach seeds on the vegetable bed where the amaranth had been, reminding them to be gentle when covering the seeds with soil. She mentioned that in just three days, they would be able to see the seeds sprouting.

The farming activities began at eight o’clock and concluded in about half an hour. During this time, the students completed tasks such as harvesting, soil preparation, seed sowing, fertilizing, and watering. Despite the sweat on their faces and the dirt on their hands and legs, everyone enjoyed the process. It was mid-April; the vegetables would be ripe for harvest by late May or early June.

“This kind of agricultural labor is hard to experience nowadays unless parents specifically take their children to the fields on weekends or holidays,” said Xu Rong-sheng (徐榮勝), chairman of Tainan Tzu Chi Senior High School’s Parents’ Association. “But here at the Tzu Chi school, we have the opportunity to experience farming right on campus.” Xu, who was volunteering in the garden that day, shared that he became a gardening volunteer when his son was in second grade at the school. Though his son is now in eighth grade, he is still leading elementary students to cultivate vegetables.

“Growing vegetables isn’t easy,” Xu added. “From germination to maturity, it requires a lot of care. When children understand how vegetables are grown, they will better appreciate what’s in their bowls and be more likely to finish their food.”

Students in the elementary division of Tainan Tzu Chi Senior High School harvest amaranth plants on campus. Participating in farming activities helps children develop a connection with the earth and nurtures a sense of gratitude for their daily food.

Food and agricultural education

Many parents struggle to persuade their children to eat vegetables and are often met with resistance, such as tightly closed mouths or tears. A psychological experiment at Yale University showed that toddlers aged eight to 18 months instinctively avoided real plants when presented with both man-made and natural objects. This avoidance is possibly an evolved survival mechanism to avoid potential poisoning or harm from thorns or fuzz. Understanding such instinctive behaviors highlights the importance of teaching children about a balanced diet and the origins of their food. Effective food and agricultural education is essential in shaping healthy eating habits and fostering a deeper appreciation for food.

Taiwan has been making efforts to promote food and agricultural education, as evidenced by the recent passing of the Food and Agricultural Education Act in April 2022. This legislation outlines six key principles: supporting local agriculture; promoting balanced diets; reducing food waste; preserving and innovating food culture; strengthening the link between food and agriculture; and advocating for sustainable local production and consumption. Encouraged by the Ministry of Education, many teachers and students visit produce farms, fisheries, livestock farms, and food processing plants to learn more about food production. Many schools even grow vegetables and fruits on campus or raise chickens to lay eggs, providing students with hands-on learning opportunities right at school.

The kitchen garden at the Tainan Tzu Chi school mentioned earlier was created even before the Food and Agricultural Education Act was passed. Yen Hsiu-wen, the director of academic affairs in the elementary division of the school, views the garden as a “landscape dining table,” allowing children to cultivate and witness the growth of fruits and vegetables they regularly consume. “Through observing, recording, and reflecting on how a tiny seed grows into a mature plant,” she explained, “children come to understand that cultivating vegetables is no simple task. They also learn that food goes through additional steps, such as transportation and cooking, before it ends up on our dining tables. Appreciating the effort involved helps develop a deeper sense of gratitude for our food.”

Successful food and agricultural education should foster a sense of connection with and care for food, the land, and all those involved in the food production process. Professor Chiu Yie-ju (邱奕儒), the director of the Master’s Program in Sustainability and Disaster Management at Tzu Chi University, in eastern Taiwan, pointed out that one of humanity’s most severe problems is the lack of understanding about how our food grows from the land, resulting in a loss of connection with the earth. When people reconnect with the land, they naturally gain security and develop inner confidence.

“Food and agricultural education should start as early as possible,” Chiu asserted. Understanding how food is grown and harvested helps cultivate much-needed virtues, including an appreciation for food, mindfulness of reducing waste, and respect for the environment.

A Well of Hope—Resolving Water Scarcity in an Indonesian Village

Text and photos by Clarissa Ruth Octavianadya

Translated by Wu Hsiao-ting

After three years of searching for a water source, Tzu Chi volunteers, with military assistance, drilled a well for a village of 600 households facing a chronic water shortage, providing them with a reliable water supply.

A villager happily uses cupped hands to scoop and drink water from the new well.

If, after three years of searching and drilling, you still hadn’t found a site with sufficient water for a well, would you continue? That was what Tzu Chi volunteers faced in their search for a suitable water source for the Indonesian village of Kuranten.

Kuranten is located in Pandeglang Regency, Banten Province. The village’s rocky soil made it difficult to find a water source for a well, leading to water shortages and significant inconvenience for its residents. In 2021, Tzu Chi began assisting the village in finding a location to sink a reliable and sustainable well. But despite 11 attempts, they were unsuccessful. Volunteer Edi Sheen (沈茂裕) shared, “We and the villagers felt very helpless, almost to the point of giving up.”

Then, in November 2023, a water source was discovered at a depth of just six meters (20 feet) in Pakuhaji Village, three kilometers (1.9 miles) from Kuranten. After three days of drilling, a well 40 meters (130 feet) deep had been established, providing a continuous flow of clean water. Water pipes, pressure- and crack-resistant, were subsequently installed to bring the well water to the 600 families in Kuranten.

Muhammad Yusep, a resident of Kuranten, played a crucial role in successfully addressing the water challenge. He had been particularly saddened to see how the water shortages in Kuranten had led to open conflict over access to water. One person had even been injured and hospitalized, and the perpetrator imprisoned. These incidents were his motivation to help find a sustainable water source, including offering his family’s land for drilling.

Jaja Raharja’s home now has enough clean water for daily use.

A well had been established in Kuranten in the past with his help, but it had run dry just two months after it had been tapped. Since a good water source could not be found in Kuranten, Muhammad thought it might be better to search elsewhere and pipe the water to the village. He thought Pakuhaji, the village where he was born and raised, might be a good place to try. The village had abundant water sources, and his parents had left a piece of land there that just might serve the purpose. He proposed his idea to Tzu Chi volunteers after gaining approval from his family. Happily, his idea was successful and a water source was discovered there.

Tzu Chi collaborated with the military to drill a well, which was inaugurated on May 2, 2024. During the inauguration ceremony, Captain Deddy Bonar Sirait urged villagers to cherish the water source, saying: “This is a gift from heaven, so please conserve water.” Since Kuranten Village doesn’t have the infrastructure to channel the well water directly to residents, the water piped from Pakuhaji is stored at the village mosque for residents to access.

Fifty-year-old village resident Jaja Raharja helped his parents fetch water from distant places when he was young. He didn’t think the problem would continue for as long as it did. “Seeing others have water parties while our village suffered from scarcity was always very distressing,” he said. “Having clean water may seem like a small matter to most people, but it was a big deal in our village…. Thank Allah, and thanks also to Tzu Chi volunteers for helping us, regardless of religion, race, or skin color. They regarded our problems as their own, which deeply moves me.”

He believes that the journey to find water sources was an important part of his village’s history and a beautiful story to pass down through generations. He noted that with sufficient water, their quality of life and economy would improve, especially their crop yields. Over 5,000 villagers would no longer have to worry about water scarcity during the dry season. “We will cherish the water source and ensure that future generations do not have to struggle to obtain clean water,” he remarked.

Text and photos by Clarissa Ruth Octavianadya

Translated by Wu Hsiao-ting

After three years of searching for a water source, Tzu Chi volunteers, with military assistance, drilled a well for a village of 600 households facing a chronic water shortage, providing them with a reliable water supply.

A villager happily uses cupped hands to scoop and drink water from the new well.

If, after three years of searching and drilling, you still hadn’t found a site with sufficient water for a well, would you continue? That was what Tzu Chi volunteers faced in their search for a suitable water source for the Indonesian village of Kuranten.

Kuranten is located in Pandeglang Regency, Banten Province. The village’s rocky soil made it difficult to find a water source for a well, leading to water shortages and significant inconvenience for its residents. In 2021, Tzu Chi began assisting the village in finding a location to sink a reliable and sustainable well. But despite 11 attempts, they were unsuccessful. Volunteer Edi Sheen (沈茂裕) shared, “We and the villagers felt very helpless, almost to the point of giving up.”

Then, in November 2023, a water source was discovered at a depth of just six meters (20 feet) in Pakuhaji Village, three kilometers (1.9 miles) from Kuranten. After three days of drilling, a well 40 meters (130 feet) deep had been established, providing a continuous flow of clean water. Water pipes, pressure- and crack-resistant, were subsequently installed to bring the well water to the 600 families in Kuranten.

Muhammad Yusep, a resident of Kuranten, played a crucial role in successfully addressing the water challenge. He had been particularly saddened to see how the water shortages in Kuranten had led to open conflict over access to water. One person had even been injured and hospitalized, and the perpetrator imprisoned. These incidents were his motivation to help find a sustainable water source, including offering his family’s land for drilling.

Jaja Raharja’s home now has enough clean water for daily use.

A well had been established in Kuranten in the past with his help, but it had run dry just two months after it had been tapped. Since a good water source could not be found in Kuranten, Muhammad thought it might be better to search elsewhere and pipe the water to the village. He thought Pakuhaji, the village where he was born and raised, might be a good place to try. The village had abundant water sources, and his parents had left a piece of land there that just might serve the purpose. He proposed his idea to Tzu Chi volunteers after gaining approval from his family. Happily, his idea was successful and a water source was discovered there.

Tzu Chi collaborated with the military to drill a well, which was inaugurated on May 2, 2024. During the inauguration ceremony, Captain Deddy Bonar Sirait urged villagers to cherish the water source, saying: “This is a gift from heaven, so please conserve water.” Since Kuranten Village doesn’t have the infrastructure to channel the well water directly to residents, the water piped from Pakuhaji is stored at the village mosque for residents to access.

Fifty-year-old village resident Jaja Raharja helped his parents fetch water from distant places when he was young. He didn’t think the problem would continue for as long as it did. “Seeing others have water parties while our village suffered from scarcity was always very distressing,” he said. “Having clean water may seem like a small matter to most people, but it was a big deal in our village…. Thank Allah, and thanks also to Tzu Chi volunteers for helping us, regardless of religion, race, or skin color. They regarded our problems as their own, which deeply moves me.”

He believes that the journey to find water sources was an important part of his village’s history and a beautiful story to pass down through generations. He noted that with sufficient water, their quality of life and economy would improve, especially their crop yields. Over 5,000 villagers would no longer have to worry about water scarcity during the dry season. “We will cherish the water source and ensure that future generations do not have to struggle to obtain clean water,” he remarked.

A Housing Project in Silaunja

By Zhu Xiu-lian and Lin Jing-jun

Translated by Wu Hsiao-ting

Photos by Hsiao Yiu-hwa

A promise of a better living environment emerges with the launch of a housing project.

Silaunja was chosen as the site for the first group of Tzu Chi Great Love Houses in Bodh Gaya. The groundbreaking ceremony for this project, consisting of 36 houses, took place on February 25 of this year. In March, during a month-long stay in India, documenting volunteers from Taiwan visited Silaunja three times in one week—early morning, daytime, and evening—to understand and record villagers’ living conditions.

Early one morning, as the volunteer team arrived at the village entrance, they saw a woman wrapped in a thin blanket, sitting with three young boys around a fire outside a house, burning dried palm leaves for warmth. Most villagers were already up, engaged in their morning routines; some were brushing their teeth with toothbrushes, while others used twigs of neem, a common tree in India.

The village lacked taps or running water. Residents typically squatted by the water pumps outside their homes to brush their teeth, wash their faces, bathe, or do laundry. Despite the presence of two relatively clean toilets constructed with foreign aid at the village entrance, residents preferred to go outdoors, often walking to the Niranjana River nearby to relieve themselves.

Earthen stoves served as open-air kitchens in front of homes. Flatbread was prepared for breakfast by hand-pressing small dough balls into round discs, rolling them thinly with a rolling pin, and then cooking them on a metal griddle. Lunch and dinner usually consisted of rice or flatbread accompanied by curry cooked with beans and vegetables. With few job opportunities, villagers spent their days squatting by their doorways, engaging in idle chatter.

During an evening visit, volunteers observed the setting sun casting a glow on the earthen platform where the groundbreaking ceremony for the Great Love Houses was held. They noticed that the platform had become a spot where children played. One boy used a stick as a bat, while another picked up anything lying around to throw. Nearby, another child rolled a small, abandoned tire with a piece of wood. Though they lacked video games or store-bought toys, the children found joy in playing with natural materials or whatever else they could find, enjoying themselves just the same.

Children in Silaunja, led by volunteers, clean up the environment. Poor public health conditions are a source of diseases.

Stronger permanent houses