By Su Fang-pei

Edited and translated by Wu Hsiao-ting

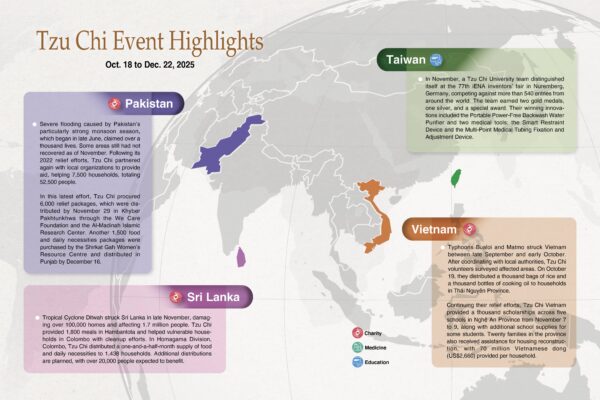

What kind of marks will the Syrian civil war leave on the children that fled from their country? A pharmacist and member of the Tzu Chi International Medical Association shares in this article her own experiences with some Syrian refugee children, and also about the work that Tzu Chi Jordan is doing on their behalf.

Su Fang-pei (蘇芳霈, middle), the author of this article, interacts with Syrian refugee children at Tzu Xin House in Amman, Jordan. You Xi-zhang

My heart ached as I was writing about Tzu Chi Jordan’s medical aid for Syrian refugee children; I couldn’t stop my tears from flowing. The Syrian people that have fled their country have been deprived of their roots and so much more. I could feel their sadness pulling at my heartstrings.

I live in Taiwan, more than 8,200 kilometers (5,095 miles) from Jordan. Though it takes nearly 24 hours to fly from my home to Jordan, I feel so close to the Syrian refugees there. What has caused the cataclysmic upheaval in their lives?

What happens in childhood has a deep, enduring impact on one’s life. That’s why it’s essential for parents to give their children enough love and a strong sense of security and trust. Sometimes I wonder if Syrian children, after enduring all the hardships caused by the war, will grow to have more psychological scars. I wonder what kind of marks the war will leave on the minds of the children who have been forced to grow up prematurely.

I’m a member of the Tzu Chi International Medical Association (TIMA). In 2017, Brother Chen Chiou Hwa in Jordan learned how I combined drawing and cello music in my art therapy activities at my pharmacy on Saturday afternoons. He hoped I could bring similar activities to refugee children in Jordan. That led me to a take a trip to Jordan in May of the same year.

Before I set off, students at the elementary division of Tzu Chi Senior High School in Hualien, eastern Taiwan, created many pictures for me to take to Jordan. While I was in Jordan, Syrian refugee children there reciprocated by drawing many pictures too. The one that impressed me the most was by Adeebah Adnan Hilal—she drew an eye shedding red tears. When I asked her the meaning of her drawing, she said, “Crying for Syria. The tears are red because they are blood tears.” Then she hugged me and burst into tears.

I held my art therapy activities at Tzu Xin House, a shelter for Syrian refugee mothers and children, located in suburban Amman. Tzu Chi Jordan helps the House pay its rent, subsidizes residents’ medical treatments, and provides tuition aid for the children there. They also help the mothers there learn marketable skills by arranging for cooking, sewing, and nursing classes.

When I first visited the shelter to conduct art therapy activities for the mothers and children, my attention was drawn to a little boy named Abdul Alaziz. He never talked or interacted with the other children. When everyone was drawing, he just sat there, his eyes bleak and lost.

I knew that he was that way because his heart had been hurt, that it ached so much that he didn’t want to say or express anything for fear that his tears would come as soon as he spoke. I thought of the boy often after that day.

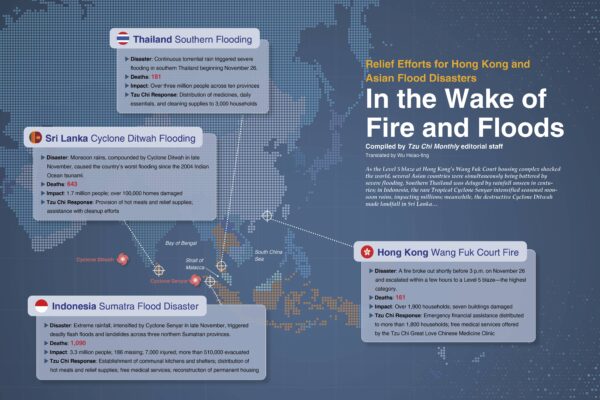

At one point during my third visit to Tzu Xin House, I felt someone tugging at my sleeve from behind. When I turned around, I saw that it was him. He pointed to some pens and paper. I realized he was finally willing to open up his heart, so I immediately asked Chen Chiou Hwa to take him to another room to draw. A short while later, Chen returned and asked me to go look at what Abdul had drawn. I did and saw that he had drawn a large blue boat with some Arabic writing above it. A teacher translated the Arabic into English: “A life-saving boat.”

As it turned out, he was expressing his longing for his father through the picture. He hadn’t seen his father since he had left Syria with his twin brother, Munir, and his mother, Nimar. His father had escorted them to a boat to leave Syria that day. Abdul had missed him dearly since.

After I interacted with Abdul that day, his appetite improved. He grew tall and strong. Once he turned 13 years of age, he was no longer eligible to stay at Tzu Xin House, according to the House’s regulations. As a result, his mother actively sought refuge in another country and eventually obtained approval for them to go to Norway.

In turbulent times, a mother will do everything she can to fend for and protect her children. Nimar was no different. Though she had heart disease, for the sake of her children, she flew with them to Norway. Sadly, she had a heart attack on the flight and passed away after leaving the plane.

When I wrote about Osama, Lujin, Yousef, and other children with medical conditions, I couldn’t help but think: how many more Syrian children are needing company to help them better move forward on their life journeys?

A drawing by Abdul Alaziz features a blue boat covered in fetter-like grid lines. The background is a blank, conveying a feeling of desolation. Abdul is expressing via this picture his pain of separation from a loved one. It took him some time to eventually be willing to communicate his feelings.

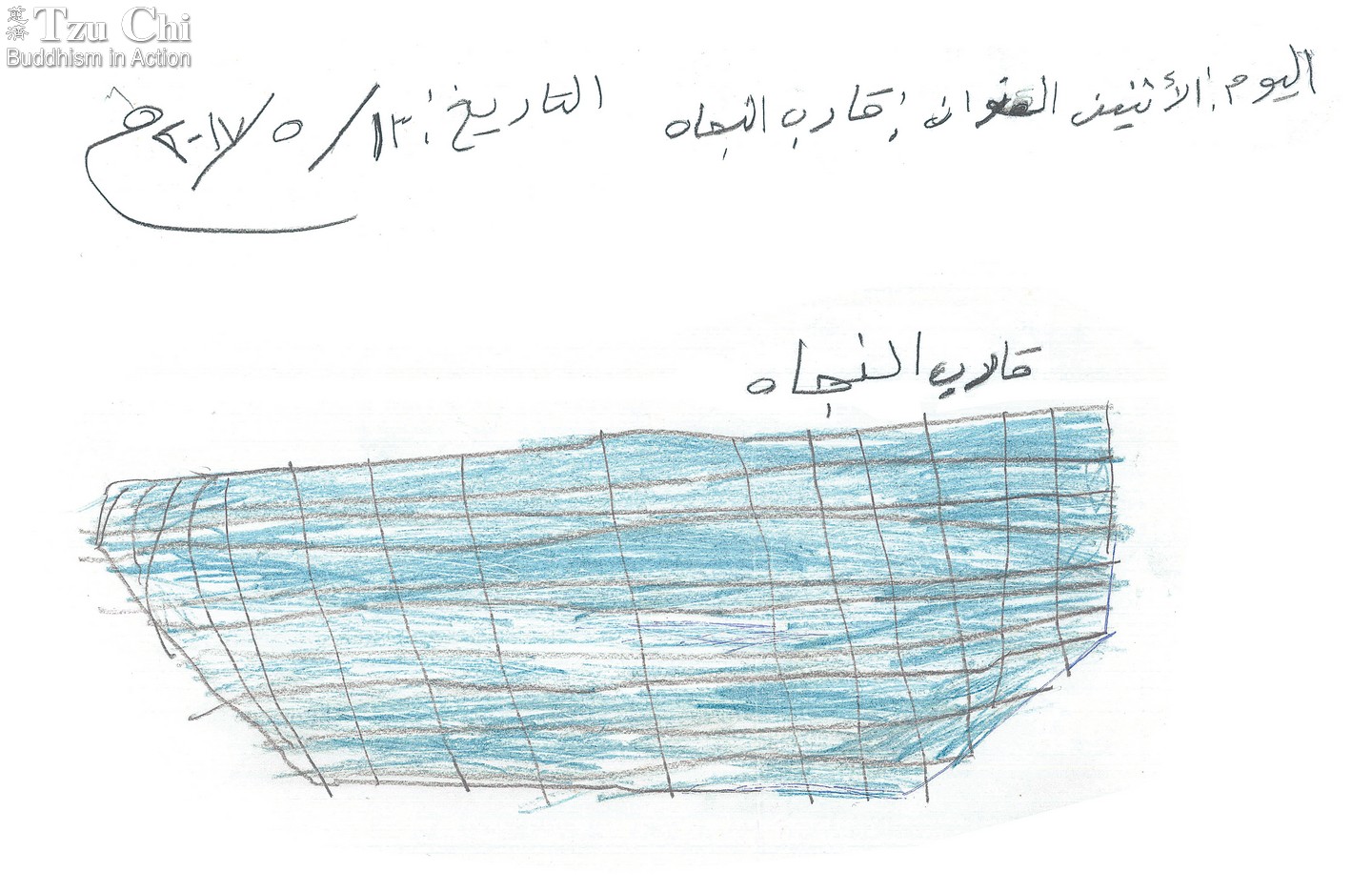

The Koran, the holy book of the Islamic religion, is the subject matter of this drawing, created by Nour Aldin Ameer. In a foreign country, one’s traditional culture and religion serve as the best reminders of one’s roots.

An immigrant helping refugees

I kept in touch with Brother Chen after my trip to Jordan had ended and I returned to Taiwan. I tried to stay updated with how the refugee mothers and children were doing.

When the COVID-19 pandemic broke out, Jordan declared a state of emergency to limit the spread of the infection. Syrian refugees in Jordan were originally allowed to work or receive subsidies from the United Nations, but the lockdown made things difficult for them. Roads were closed by the military and vehicles weren’t allowed to travel freely. Worried that some refugee families would have difficulty getting by, Chen walked to obtain subsidies for them.

The pandemic eased in 2022, and Tzu Chi Jordan was finally able to resume their regular aid distributions and free clinics. But the Tzu Chi branch hadn’t stopped helping people with their medical needs, not even during the pandemic.

Chen told me that Tzu Chi has worked with medical institutions, such as Al Bayader Hospital and Akilah Hospital, since 2013 to provide surgeries for refugees. This cooperation has continued for more than nine years now. Osama Atari, superintendent of Al Bayader Hospital, is even planning to use the second floor of the hospital as a dedicated ward for patients whose treatments are being financed by Tzu Chi. The King Hussein Medical Center, on the other hand, is helping Tzu Chi take care of some cancer patients.

The incidence of cancer among Syrian refugees is relatively high. It might be connected with the trauma from having to flee a war, or with living in unsanitary conditions. It might be due to a lack of health knowledge, stress, or persistent negative emotions. Among the refugees Tzu Chi has helped obtain treatment, many were widowed mothers and children. Though there are other international NGOs in Jordan that offer financial aid to refugees who need medical attention, there is often a limit on the aid they can provide. Surgery is expensive locally, and sometimes the aid they provide to a patient is only enough to cover a small part of their medical expenses. Refugees can be left in the lurch if they are unable to get help.

“Sometimes we also find ourselves in a dilemma because we have many people to help and yet only so much money to help them,” Chen said. “Besides, will they receive the best care after we decide to help them?” It takes wisdom to make the best decisions. Chen often tosses and turns in bed trying to decide what’s best to do.

Because they often feel insecure, refugees tend to be on their guard. Syrian doctors who have been able to find a job in Jordan because of their expertise are no exception. It often takes Tzu Chi volunteers a lot of time to win their trust when they are reaching out to help them.

Jordan and Syria are both Arab countries, and the same language—Arabic—is used in both nations. In the past, Syrians went to school and received healthcare in their country for free. The country’s social welfare system was comprehensive, and people were well provided for. Jordanians loved to go to Syria. In the early years, when Jordanians went to Syria to attend school, they were not only exempted from tuition fees, but they could also receive stipends for their living expenses. For example, Abeer Aglan M. Madanat, a Jordanian pharmacist and a TIMA member, had attended school in Syria before returning to Jordan to work. Sometimes it cost but half as much driving from Amman to Damascus, two hours away, to have a meal or to shop. But that’s all in the past. The two countries have long since switched places. It is easy to imagine what Syrians feel about this.

Brother Chen cares a lot about refugees. He also cares a lot about the team of Syrian doctors who have been working with Tzu Chi to provide medical treatment to their fellow Syrians. “I once asked these physicians why they didn’t take their families and flee to Europe,” Chen said. “They told me they didn’t want their children to forget their roots. They said that it would be as good as abandoning their roots if they forget their traditional culture and religious beliefs.”

It has been 48 years since Chen himself first set foot in Jordan. Highly skilled in Taekwondo, he was sent in 1974 by Taiwan’s Ministry of National Defense to Jordan to serve as the head martial arts coach for the Royal Guards. He has come a long way since then, from an expatriate who had difficulty communicating with local people due to the language barrier to the head of Tzu Chi Jordan. For many years now, he has helped Tzu Chi carry out charity work in Jordan, doing everything he can to help refugees and destitute families in the Middle Eastern country.

He recalled his early days in Jordan. He once walked for more than an hour to a market to buy a cleaning brush, only to find after he arrived that he couldn’t say the name for it. Chewing Jordanian flatbread with effort, he missed food back in Taiwan. It was said that Jordan had the best yogurt, but even after two weeks he couldn’t get used to its taste, not even with his nose pinched. When a friend came from Taiwan to visit him and made some fried rice for him, tears came to his eyes as he ate it. He eventually came to realize that nothing was easy in life.

Chen is a Buddhist and Tzu Chi a Buddhist organization. Because of this, it is not easy to get people in Jordan, a Muslim country, to join Tzu Chi as volunteers and work with him to help local needy people. Limited manpower has made his work in Jordan more of a challenge. He and other local volunteers have encountered so many difficulties providing help to refugees in Jordan that he once thought of scaling back their work for this group of people. “Fortunately, I have Master Cheng Yen’s teachings to rely on,” Chen said. “They have guided, supported, and kept me going through the difficult times when I’ve felt helpless.”

It has not been easy, but Chen has managed to carve a path for Tzu Chi’s charity work in Jordan, bringing light to people in need, including Syrian refugees in the country.

Volunteer Chen Chiou Hwa greets a Syrian child who had received cleft lip surgery with the aid of Tzu Chi. Chen has helped Tzu Chi carry out charity work in Jordan for many years. Wang Jin