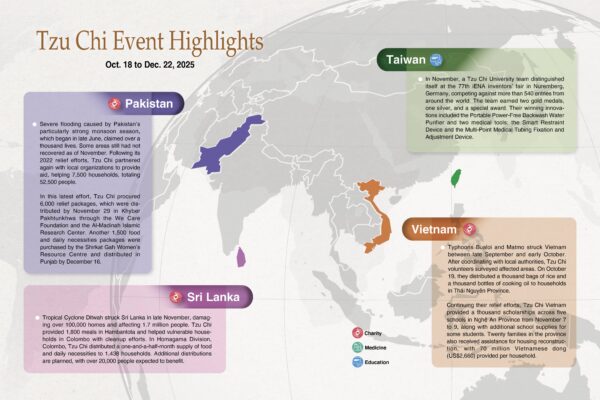

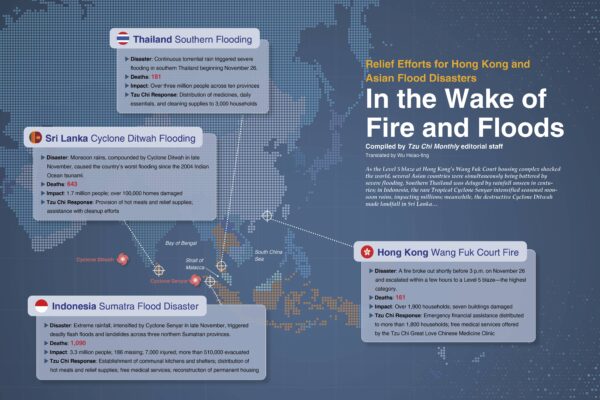

By Tan Kim Hion and Chan Shi Yih

Translated by Wu Hsiao-ting

Tzu Chi volunteers in Malaysia, working with the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, delivered emergency cash to refugees to help them weather the economic impacts of the coronavirus crisis.

A medical worker from the Tzu Chi Free Clinic in Kuala Lumpur photographs a refugee after delivering cash to him. This was part of an aid project Tzu Chi Malaysia and UNHCR jointly launched to help refugees in Malaysia weather the coronavirus pandemic. Photographs were taken for proof of receipt in lieu of a signature from the refugee to maintain social distance. WEE SUAN YEAN

How often do we complain about our jobs or that our houses are too small? The next time you are tempted to do so, remember that somewhere in the world are people fleeing their home countries to escape from war or from racial and religious persecution. Their journeys to safety are often grueling, a matter of life and death for them. Even if they make it safely to another country, does that guarantee a good life? For many refugees in Malaysia, the answer is “no.”

According to the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), nearly 180,000 people had registered as refugees or sought asylum in Malaysia as of March 2020. Of that number, 154,460 refugees were from Myanmar, with more than 100,000 of those being Rohingya. These staggering numbers represent a low estimate—the actual number of refugees is believed to be higher.

Malaysia was not a signatory of the 1951 U.N. Convention on Refugees, so all refugees, even those possessing UNHCR refugee cards, are considered illegal immigrants in the nation. As such, they are not entitled to work. But what can they do? They have to survive, so they take jobs anyway, despite the risk of arrest or deportation. They might make a living by moving goods at the Selayang wholesale market in Kuala Lumpur, or by working as construction workers, or by serving as waiters at restaurants. Due to their illegal status, they are particularly vulnerable to exploitation by their employers.

Shakamatddin Nabi Husson, 22, is a Rohingya from Myanmar. His father sold land in Myanmar to pay smugglers to get him into Malaysia by boat. Shakamatddin successfully made it to Malaysia, but his father, brother, and sister were all sadly killed by Burmese soldiers. The only other person in his family to survive was his mother, who ended up in Bangladesh.

Shakamatddin worked as a construction worker in Mentakab, in the state of Pahang, before the COVID-19 pandemic. His daily wage was 50 ringgit (US$12). He took good care of his mother. Of the 1,500 ringgit (US$350) he earned every month, he kept only 500 for himself. He sent the rest to his mother in Bangladesh.

Mobilizing for refugees

Malaysia has not been spared from the coronavirus pandemic. To rein in the infection, the country implemented a nationwide Movement Control Order (MCO) on March 18. Just as similar lockdown measures in other countries have hobbled their economies, many people’s livelihoods in Malaysia have been affected as well.

The economic fallout has been especially hard on refugees like Shakamatddin. He was just barely scraping by before the pandemic, so the lockdown just added insult to injury. “I was able to get by before the implementation of the MCO,” said the young man. “But now with my income gone, I often go hungry [to make what food I have last longer]. My mother in Bangladesh has had to do the same.”

Many refugees, at their wits’ ends, turned to UNHCR for help. So many phoned the agency that the helpline was constantly busy. One refugee said that he couldn’t get through, even after nearly 60 attempts.

Overwhelmed by the large number of requests for help—over 4,000 households according to UNHCR’s estimates—the agency decided to partner with Tzu Chi to help refugees weather the COVID-19 crisis. Because refugees in Malaysia are spread throughout the country, the project was designed to cover many districts, including Kuala Lumpur, Selangor, Penang, Johor, Kedah, Kelantan, Melaka, Negeri Sembilan, Pahang, and Perak.

Extending care and support to the needy is routine work for Tzu Chi volunteers. When a family is referred to Tzu Chi for help, volunteers typically visit them personally to learn about their situation and evaluate how the foundation can help. But the current situation is far from typical. Due to the Movement Control Order, volunteers could only phone the refugees on the list provided by UNHCR to obtain necessary information about them. Volunteers then sent whatever data they could gather to the Tzu Chi Kuala Lumpur and Selangor branch office. At that point, employees at the Refugee Affairs Department at the office would evaluate and double-check the information. If approved, volunteers received the grants and then set out to refugees’ homes to deliver the money to them.

The first round of phone calls was kicked off on April 8. Two days later, the Refugee Affairs Department staffers assessed the information that had been submitted. Soon thereafter, volunteers received money for the families who had been approved for aid. The volunteers promptly fanned out to distribute it.

Volunteer Yap Poh Wee (葉寶蔚) helped coordinate the project. She admitted that it wasn’t an easy mission to pull off. She talked about some of the challenges they had encountered: “Because most refugees could only speak simple English and Malay, the volunteers who made the phone calls and distributed the cash had to be able to speak both languages. When they went out to deliver the money, only one person per vehicle was allowed, in accordance with the Movement Control Order. Only two volunteers were allowed to be present when the cash was given out. We also had to report our trips to the police in order to deliver the money. The schedule was very tight.”

Yap made a point of reminding volunteers each time they set off to make distributions to be sure to wear a mask and their volunteer ID cards, and to carry the documents issued by the police and UNHCR. She also asked them to be sure to maintain adequate social distance with the refugees. Because of that, no signatures were required to confirm that refugees had received the money. Photos were taken instead for proof of receipt.

Shakamatddin Nabi Husson, a Rohingya refugee (second from left), received cash aid from Tzu Chi volunteers on April 24. Volunteers learned when conducting the first batch of deliveries that most refugees were running out of food. In response, they purchased food out-of-pocket for refugees during the second batch of distributions, and delivered it to refugees along with their cash aid. CHEW YEE LENG

An angel’s voice

Tang Lai Kuen (鄧麗娟) was one of the volunteers who helped make the phone calls. She hadn’t had much contact with refugees before the project, so she wasn’t very aware of their situations and the difficulties they faced in life. It was only through the project that she came to learn more about the sad stories of this group of people.

“When I first started to make the phone calls,” Tang said, “I told myself that the refugees must be experiencing a lot of anxiety due to the pandemic. I reminded myself to be especially gentle when I talked to them. During the phone calls, I took care to be slow and gentle. A Rohingya refugee I talked to surprised me by calling me an angel.”

Tang remembered how that refugee, Muhamad, had poured out his experiences when she asked with concern how things were going for him. Muhamad was a young father. He lived with his wife and 16-month-old son. Their son had Down syndrome, so to make it easier for Muhamed to take his son to the doctor, he chose to do only part-time jobs. Making ends meet was already a challenge for him and his family, but the coronavirus and the resulting Movement Control Order just made things worse. Deprived of all means to make money, he wasn’t able to pay the rent or buy formula for his son. He couldn’t even take the little one to the doctor. He was anxious about running out of food and being turned out of their home by their landlord. Both he and his wife were very depressed.

Muhamad’s helplessness and fear tugged at Tang’s heartstrings. As soon as she put down the phone, she uploaded the family’s information to staffers at the Tzu Chi Kuala Lumpur and Selangor office. She kept emphasizing to them what a tight spot Muhamad and his family were in, and urged them to quickly process the case so the family could receive help as soon as possible.

Because Muhamad had previously taken his son to the Tzu Chi Free Clinic in Kuala Lumpur for medical attention, his information was quickly confirmed. Volunteers were able to deliver cash to Muhamad on the second day after Tang talked to him on the phone. She was later relieved to learn that he had used the cash aid to buy food and take his son to the doctor.

After he received the cash aid, Muhamad wrote to Tang to express his gratitude. He said that he was deeply grateful to Tzu Chi and UNHCR for helping him when he was at his most helpless and despairing. He said he would never forget such kindness, and he thanked Tang for her gentle, caring manner. He said her voice was like that of an angel. His heart was warmed to no end. He wished Tang and all the others who had helped him would have happiness, good health, safety, and peace.

She wrote to him in reply: “You don’t have to thank us. We were just doing what we Tzu Chi volunteers should do. Our Master [Dharma Master Cheng Yen] always teaches us to give without asking for anything in return. Your child chose to be born into your family because you have the love required to take care of him. Never give up hope. Love him as much as you can. Someday, when you can, reach out to help others. I give you my very best wishes.”

By the end of April, volunteers had completed five rounds of phone calls and cash deliveries. They worked a total of 8,000 shifts and helped 2,876 families. UNHCR and Tzu Chi have extended the project to help more refugees ride out this difficult time, and volunteers have followed up with more phone calls and deliveries. It’s a difficult mission to carry out, but no one minds the hard work. Everyone appreciates the opportunity to help a group of people forced out of their home countries into an unknown future.

Volunteers in Seberang Perai, Penang, double-check information before handing over cash to refugees. It took the volunteers some time to locate this residence, due to the complicated house numbering system in this rural district. Because 16 refugee households lived at the same address, the volunteers took extra care to confirm the identifications of the recipients and distribute cash to them. LIM CHOON NYA