By Jessica Yang

Edited and translated by Wu Hsiao-ting

Noto has a way of winning hearts, making it easy to become emotionally attached to the area. As the region works toward recovering from the January earthquake, we continually ask ourselves: what more can we do to help?

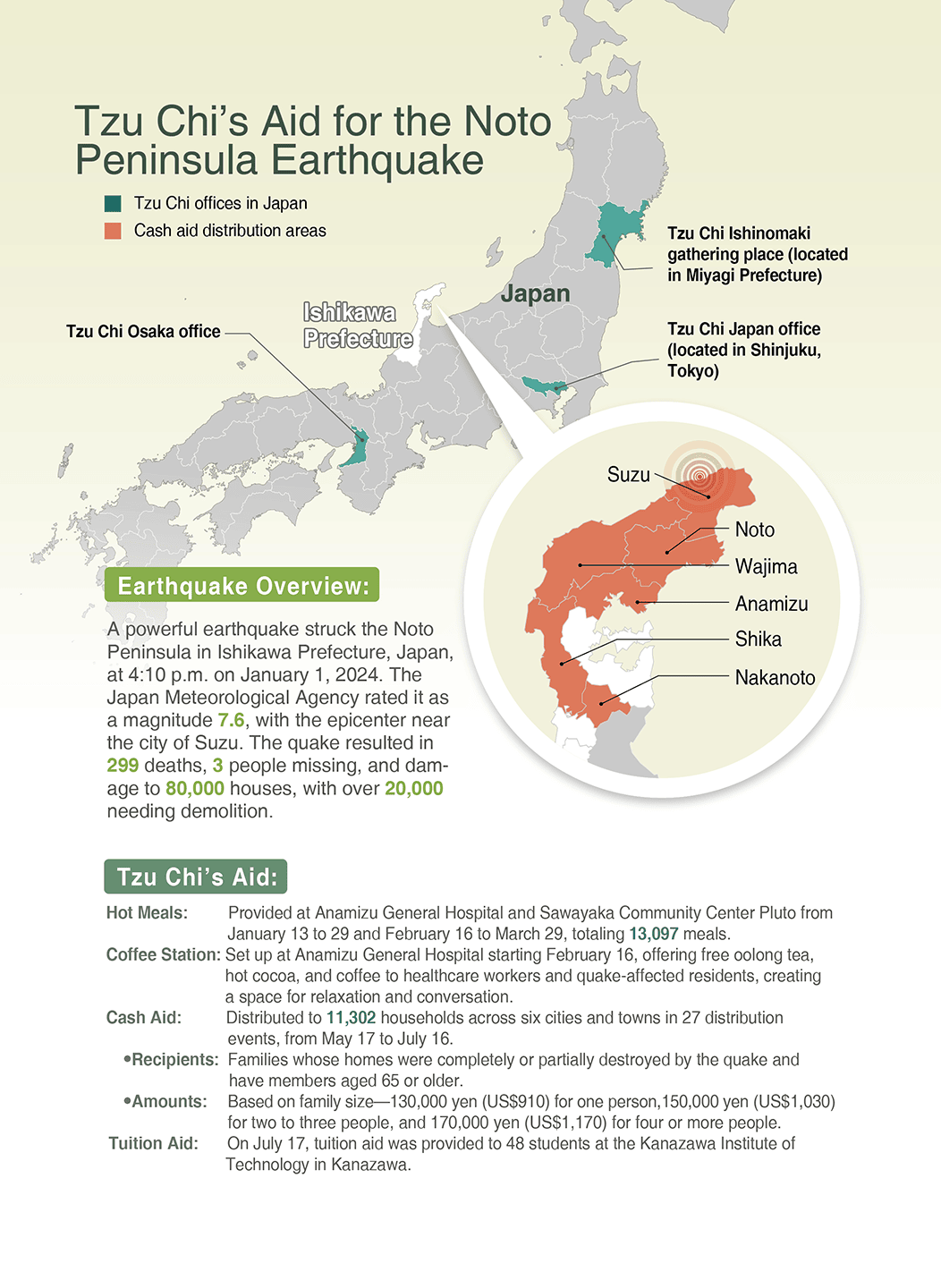

After a strong tremor struck the Noto Peninsula in Japan on January 1, volunteers repeatedly traveled to affected areas like Wajima and met with government agencies to discuss aid models. Chen Jing-hui

There is an old Japanese proverb that says, “The people of Noto are gentle and kind, and even the land reflects this.” The Noto Peninsula, located in Japan’s central Ishikawa Prefecture, extends over a hundred kilometers (62 miles) into the Sea of Japan. After an earthquake struck the peninsula on January 1, Tzu Chi launched disaster relief efforts. This led to my visits as a reporter for Tzu Chi’s Da Ai TV. I am grateful for the opportunity to deeply connect with this land through my assignment.

When people hear about the Noto Peninsula, they often think of satoyama and satoumi. But what are these concepts?

Satoyama refers to rural areas, including villages, farmland, forests, grasslands, bamboo groves, and more, managed by people to create and maintain rich natural environments. These areas support diverse plant and animal life while preserving and nurturing unique traditional cultures. Satoumi pertains to coastal areas where people benefit from the sea’s bounty while also protecting marine life.

The Noto Peninsula is characterized by low mountains and hills. With the peninsula surrounded on three sides by the Sea of Japan, its coastline is rich in biodiversity. The residents’ lives have always been intertwined with the sea, farmland, and forests. They have preserved historic festivals and continue to practice traditional crafts passed down through the centuries, such as Wajima lacquerware and Suzu pottery.

Residents of the Noto Peninsula live in harmony with nature, respecting the heavens and cherishing the earth. This way of life has been inherited for generations. In June 2011, the area’s satoyama and satoumi were designated a Globally Important Agricultural Heritage System by the United Nations’ Food and Agriculture Organization, bringing global attention to the region.

I visited the Noto Peninsula for the first time in April 2024 with Hsieh Ching-kuei (謝景貴), advisor for the CEO’s Office of the Tzu Chi charity mission, and Teng Chih-ming (鄧志銘), a colleague from Da Ai TV. Brother Hsieh remarked at the time, “Tzu Chi’s basic principles for disaster relief have always been to attend to both the physical and emotional needs of survivors to help them return to a normal life. However, with global warming accelerating, we need to incorporate innovative methods of aid. Beyond attending to survivors’ physical and emotional needs, we should integrate the concept of ‘sustainability’ into the recovery process.”

This made me wonder: aside from distributing cash aid to affected households, what more can we do for Noto’s agriculture, cultural assets, and elderly care? Recognizing the potential for a new model of international disaster relief for Tzu Chi, we decided to focus our report on these areas while documenting the region’s recovery efforts. During months of filming across multiple trips, we witnessed the community’s resilience and unity and were deeply touched by the unique warmth and hospitality of the Noto Peninsula.

Devastated

The breathtaking scenery of Noto immediately captivated us as we drove onto the main access road to the peninsula in April. The azure Sea of Japan was on one side, and lush green hills on the other. For a moment, I felt as though I was driving along Taiwan’s Hualien-Taitung Coastal Highway. The stunning views almost made us forget that the Noto Peninsula was a region recovering from an earthquake.

As we continued our journey, the landscape began to change. Construction vehicles and repair crews became more frequent, and the sight of buckled and cracked roads grew common. It was easy to imagine how isolated the Noto Peninsula must have felt in the early days after the quake.

Wajima lacquerware artist Hiroyuki Ejiri, whose house is by the sea between Wajima and Suzu, shared his experience of the earthquake. He recounted how the tremor was so intense that he and his family struggled to stand and had to run outside for safety. Observing the sea water receding, they feared a tsunami and quickly moved to higher ground. Fortunately, the tsunami did not materialize. After the tsunami warning was lifted, he attempted to drive his family to Kanazawa for refuge. “However, both the road to Wajima and the road to Suzu were cut off, and the phones were down. We were completely isolated,” he said. “The roads were reopened three days later, but getting to Kanazawa, which usually took two hours, took us nine hours that day.” Hiroyuki Ejiri’s helplessness at the time mirrored that of many local residents.

When we returned to the Noto Peninsula five months after the earthquake, we saw ongoing infrastructure restoration projects along the way. However, upon entering the heavily damaged city of Wajima, we found many buildings still lying in ruins where they had collapsed. Wajima, situated next to the Sea of Japan, had once been a beautiful coastal city renowned for the Wajima Morning Market—one of Japan’s three major morning markets and the city’s most bustling and prosperous area. Tragically, the powerful earthquake triggered a fire that raged for 14 hours, destroying over 200 buildings in the market area. Additionally, more than 15,000 houses throughout the city were either completely or partially destroyed or damaged by the earthquake.

Wajima resident Kensei Sumi said that about 80 percent of the collapsed and damaged houses in the city had remained untouched. He also mentioned that clearing the ruins was expected to take two years, with rebuilding projected to take three to four years. “My house was marked as uninhabitable,” he said, “but staying in the evacuation center is very inconvenient. I still prefer my own home.”

Roses bloom beautifully in June at a residence in Machino, Wajima. The garden remains lovely, but the owner who planted the flowers can no longer live in the damaged home. Lin Ling-li

Pressing on

Wajima lacquerware, designated an important intangible cultural property by the Japanese government in 1977, is a traditional craft in which Wajima residents take great pride. Many shops and workshops specializing in this craft at the Wajima Morning Market were destroyed by the earthquake and its aftermath.

Lacquerware artist Sushii Tatsuya showed us his devastated workshop. This building was severely tilted, with damaged beams and pillars and a buckled floor. Materials for making lacquerware were scattered everywhere. The government’s red notice on the building indicated it was uninhabitable and had to be demolished.

“This workshop is where I built everything from the ground up,” he said. “It was created with all my heart and soul. It’s as important to me as my life. The Japanese phrase ‘isshokenmei’ [putting one’s whole heart into something] perfectly captures my state of mind. If this place is demolished…” He choked up, unable to continue, his tears reflecting his profound attachment to his workshop and his sense of helplessness.

During our visit, we witnessed the plight of quake-stricken residents and their inexpressible suffering, yet also their resilience and warmth. Mushroom farmer Masaharu Takamori shared, “My house was deemed half-destroyed. The damage is significant, but I am more concerned about the elderly residents in the mountains. About 70 percent of the area is in a terrible state. The severity of the impact is such that you can’t find it in your heart to say ‘keep going’ to the people there… But still, everyone must keep going and move forward.” Despite his own challenges, his primary concern was for his fellow villagers.

Similarly, Katsuyoshi Shuden, a farmer from the town of Noto, prioritized his community. His farmland suffered extensive damage, with losses difficult to estimate. When we met to film how he was restoring his irrigation system, Mr. Shuden received a warm hug from Brother Hsieh. Shuden said, “Taiwan has recently experienced an earthquake too. Thank you for still coming to offer care to us.” He then took out a bag from the trunk of his car, containing three metal boxes with the coins he had saved to help others. He donated the money to Tzu Chi.

We asked him about the most difficult challenge since the earthquake. With eyes moist and rimmed with red, he said, “I’m more concerned about the disappearance of our settlement than the damage I suffered. Our elderly population is large, as the younger generation has been moving away. The earthquake has worsened this situation, and many people feel emotionally empty.”

Every interviewee we met was focused on their fellow villagers, not themselves. They are striving to rebuild with their own strength, not just for themselves but for the entire community, supporting each other. This resilience and unique warmth define the spirit of the Noto Peninsula.

Noto has a way of winning people’s hearts, and it’s easy to become emotionally attached. The pure, kind, and sincere people of Noto continually inspire me to think about how we could further support their recovery.

Mushroom farmer Masaharu Takamori is concerned about how the older people in the mountains will rebuild their lives after the earthquake. Jessica Yang

Grateful for this land and its people

Brother Hsieh often reminded us during our visits to Noto, partly to motivate himself, “Tzu Chi’s new international disaster relief model may not succeed; you might end up recording a failed process.” On one occasion, resting his right hand on his chin and frowning, he said, “The wisdom of Noto’s satoyama and satoumi has been passed down through generations, with sustainability woven into their way of life. If we can help farmers here achieve international sustainability certification and increase the value of their rice during their recovery, that would be wonderful.”

When Wajima lacquerware artists expressed concerns that their centuries-old craft might disappear, Brother Hsieh wondered, “Is there a public welfare model that could help these artists restart their workshops?” After learning that the earthquake had damaged all the kilns used by Suzu pottery artists, affecting the livelihoods of 54 people, he asked, “Let’s think together. Is there any way to let more Taiwanese people know about Suzu pottery?”

Frankly, I’m not entirely sure what Tzu Chi’s new international disaster relief model entails. What I do know is that before the interviews, we thoroughly researched the life and culture of the Noto Peninsula. During the interviews, we visited town after town and village after village, explored the lives of the locals, and learned their true needs. Only then could we discuss effective ways to support their recovery and prosperity.

As Tzu Chi approaches its 60th anniversary, we remain committed to our mission of relieving suffering and giving joy, whether through charity or international disaster relief. As I understand it, the “new model” involves aligning with international trends and global sustainability while standing together with the locals and developing solutions collaboratively.

Our documenting team first visited the Noto Peninsula in late April this year. Since then, we have made three trips totaling over 60 days. Besides developing an attachment to this land, I feel as though we are deeply loved by it as well. Whenever I needed materials and stories, the locals would arrange them for me, making me profoundly grateful for this land and its people.

As I reviewed footage and wrote scripts in the early mornings, I reflected on how well the beautiful and peaceful Noto treats its people, and how the people, in turn, love and respect the land. Even when natural disasters cause severe damage and hardships, the resilience of both the land and its people shines through. The community’s mutual support and trust, combined with their kindness, create a powerful force for good.

Natural disasters will only increase in the future, but I believe that maintaining this spirit of kindness and resilience will help everyone, no matter where they are, face and overcome their challenges.