By Yeh Tzu-hao

Abridged and translated by Wu Hsiao-ting

Photos by Hsiao Yiu-hwa

While fast fashion has spurred purchases, it has also resulted in a lot of waste. The environment is paying the price.

An employee at a clothes recycling plant sorts garments from a mountain of clothing.

Announcements from a public address system advertising ongoing special discounts could be heard periodically in the clothing section of a department store in New Taipei City, northern Taiwan. They were designed to entice shoppers to open their wallets. The cheapest items of clothing sold for just a hundred Taiwanese dollars (US$3.3) each—less than a meal at an inexpensive restaurant.

Fast fashion churns out new collections at break-neck speed and at easily affordable prices to keep consumers around the world buying. Many people now happily and frequently go on shopping sprees to renew their wardrobes. In Taiwan, long gone are the days when people were generally poor and some even had to wear garments made from the sacks that had been used to contain flour donated by the United States. No one thinks of those old Chinese adages extolling the virtue of frugality when they buy and dispose of clothes faster than the clothes go out of style.

According to statistics released by Taiwan’s Environmental Protection Administration, 78,951 tonnes (87,028 short tons) of clothes were recycled across the island in 2020. That’s about 11 items of clothing, on average, per person per year. With so much clothing being thrown away, dealing with the resulting waste has become a challenge.

Supply outstripping demand

“Many recycling merchants no longer accept secondhand clothing,” said Zhang Han-jun (張涵鈞), head of the Section for the Promotion and Development of Environmental Protection Work at Tzu Chi headquarters in Hualien, eastern Taiwan. “Some recycling merchants who have long worked with us are still willing to help out, but the amount they can accept is limited.”

When recycling dealers are taking in fewer and fewer used clothes—or refusing them completely—many Tzu Chi recycling stations have no choice but to stop accepting them too. This phenomenon is reflected in the declining amounts of clothing taken in by Tzu Chi recycling stations across Taiwan over the last five years. In 2017, 5,000 tonnes (5,510 short tons) of used clothes were accepted, but that dropped to less than 4,000 tonnes in 2018, and continued to plummet through 2019 and 2020. In 2021, only 2,300 tonnes were accepted. Although Tzu Chi recycling stations were temporarily closed for a time in 2021 due to the pandemic, the drastic reduction five years in a row reflects the general unpopularity of secondhand clothes on the market.

For this article, my photographer and I visited a used clothes recycling plant in Wugu, New Taipei City. In a large space built of corrugated sheet metal, we saw a multicolored mountain of clothes nearly four stories high. Employees sat at the foot of the clothing mountain, sorting one garment after another. The pile of clothes was so large it was easy to miss the workers if you didn’t look closely.

“We receive and ship out clothes every day,” said Wu Ji-zheng (吳基正), the owner of the business. “About 500 tonnes of clothes are processed here at our factory every month. The quality of recycled clothes is getting worse and worse, so an increasing amount is going straight into the trash.”

Wu explained that since fast fashion became a trend, people have tended to purchase inexpensive but low quality clothes in large quantity. Not only are the materials used to make the clothing worse, but the workmanship is often subpar too. Given those factors, the decline in quality of the clothes that end up at his factory comes as no surprise. Generally speaking, only 30 to 40 percent of the clothes his factory takes in are good enough to be resold.

Contributing to the challenge of running a recycled clothes business these days is a reduced demand for such garments. “Fewer and fewer countries are needing secondhand clothes,” Wu said. “More than a decade ago, most of our used clothing was sold into China. Now that their economy is doing better, they have become an exporter of used clothes themselves. Some Southeast Asian countries have followed the same path.” Wu recalled that secondhand clothes from Taiwan used to be very popular—buyers would gladly accept even school uniforms bearing embroidered names. But now, with the supply outstripping demand, many of his fellow recyclers have had no choice but to close. “I wonder what we are going to do if one day Africa begins turning away used clothes,” he said with worry.

The fashion industry churns out a gargantuan number of garments every year, catering to the needs of consumers from all walks of life.

A shadow over the fashion industry

Owners of recycled clothes businesses in Taiwan are up against other challenges, such as higher labor costs and rents than those faced by their competitors in other countries. Taking everything into account, Wu said frankly that he might fare better if he just shutters his business and rents his factory out to others. But he bites the bullet and keeps going because of a sense of social responsibility.

“I employ more than a hundred people,” he said, as he looked at his employees organizing clothes or operating forklifts to stack bundles of clothing in the factory. “Many of them are middle-aged or older people, or have disabilities. We also work with about 20 social welfare groups in managing clothes recycling bins.”

Social responsibility aside, he doesn’t want to see clothing that can still be put to use go to waste. “If we quit,” Wu said, “the government will have to take care of all the discarded clothes. What can they do but burn them?” Even burning them isn’t such an easy chore in Taiwan. According to Wu, the incinerators used in Taiwan are generally older models, which can stand only lower heat. The heat produced by burning clothes is, however, higher than these older-model incinerators can take. To prevent the equipment from being damaged, used clothes are usually mixed in with other types of garbage to be burned, so only a small amount of clothing is put in with each load. “If we don’t work to export used clothes,” he said, “all of them will end up as garbage to be incinerated. If we keep going, we can at least allow some of the clothes to be used again.”

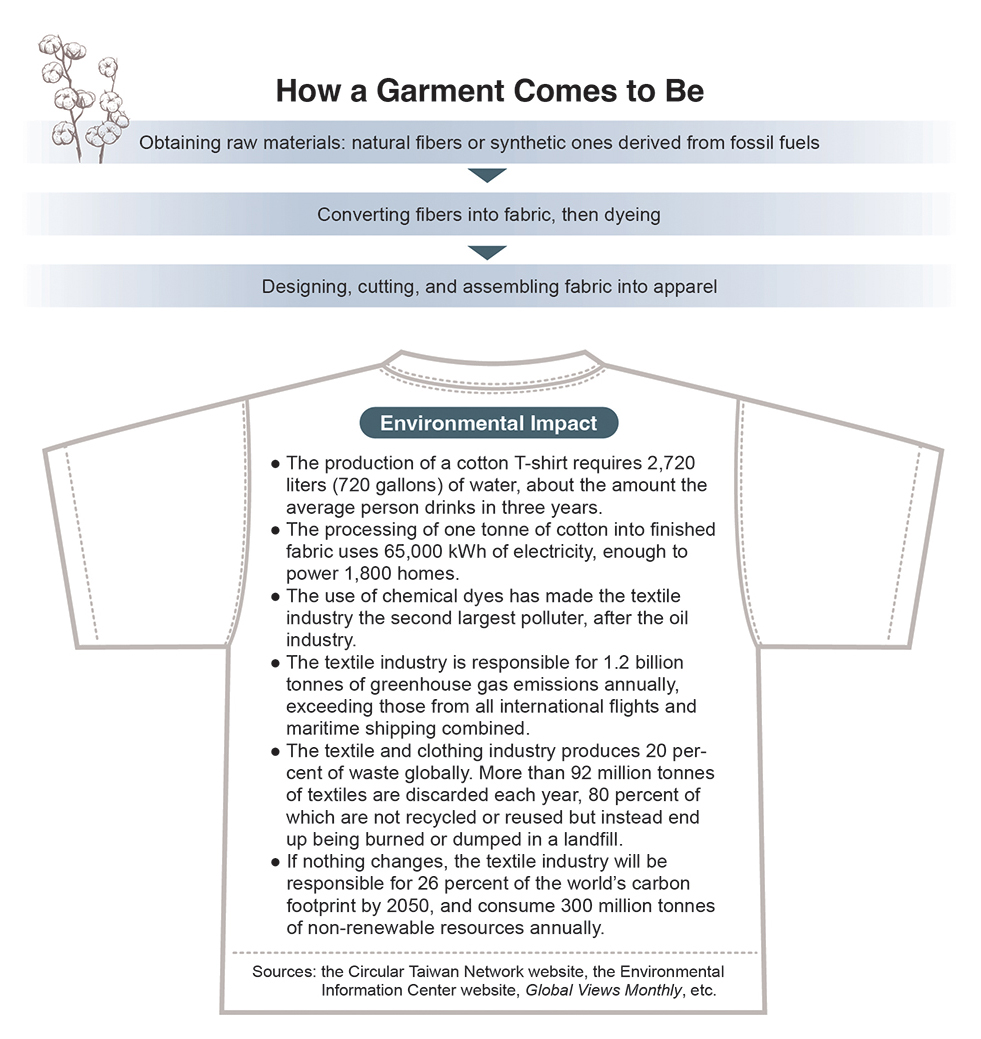

Coupled with the problem of waste is the impact the fashion industry is having on the environment. Not many are aware of it, but the textile and fashion industry is the world’s second largest source of pollution, just after the petro-chemical industry. In order to evade the stricter environmental laws enforced in advanced countries, many textile companies have moved their production lines to poorer countries where the laws and supervision are more lax. This has led to irreversible damage to the environment in those countries.

In 2018, a TV news crew from Tzu Chi’s Da Ai TV visited Bangladesh, one of the world’s largest garment exporters, to report on the problem of pollution caused by the textile industry. The TV crew was accompanied by environmental engineering experts from Chang Jung Christian University in southern Taiwan. When the team arrived at a textile factory located in a suburb of Dhaka, the capital of Bangladesh, to collect samples from the wastewater discharged by the factory, they found the water to be of a deep blue color. They tested it, and found the pH value over ten, indicating the water was strongly alkaline. In fact, one of the researchers was splashed with the water while collecting the samples, and experienced a burning sensation where the liquid landed on his arm. The team discovered that the wastewater discharged by the factory had polluted the soil and irrigation water for nearby farms, affecting crop yield and threatening the health of local residents.

In addition to the problems mentioned above, there are also issues of labor rights. Fast fashion requires more than cheap materials to work and be profitable—it needs cheap labor as well. A math teacher at El Menahil International School in Turkey once worked in a garment factory after he had fled the civil war in his home country of Syria. “A coworker of mine [at the factory] was just eight years old!” he exclaimed.

Fortunately, since the international community has been paying closer attention to corporate social responsibility in recent years, quite a few fashion brands have promised publicly to safeguard their workers’ rights and protect the environment in the operation of their businesses. This is a positive development without a doubt. But to solve the fast fashion problem at the root, consumers will have to play the biggest part.

Tzu Chi and its partners distributing blankets and secondhand clothes to people in the West African country of Sierra Leone in 2019

No buying on a whim

Chen Hwang-yeh (陳皇曄) teaches at the Marketing and Distribution Management Department of the Tzu Chi University of Science and Technology, in Hualien, eastern Taiwan. She recommended that everyone use a “green consumer mentality” when it comes to buying clothes. She suggested you ask yourself, “Do I really need this item of clothing, or do I only want it?” She continued, “Don’t buy on impulse when you see something you fancy. Think before you make a purchase. Avoid overconsumption.”

Consumers can also help mitigate the environmental impact of fast fashion by shopping secondhand or by donating the clothes they are no longer wearing. “When you do buy clothes,” suggested Wu Ji-zheng, the used clothing business owner, “go for those that are made from better materials and that will be more durable. If there are clothes you want to donate, please sort them properly before you do.” Wu said that he had seen in piles of used clothes those so worn out they were not fit for wearing any more. He had also seen clothing covered with dog hair. “If your clothes are in such shape that they belong in the trash, dispose of them as such.”

Though we don’t need to be so frugal that we deny ourselves what we need, maintaining habits that contribute to the sustainability of the environment is the duty and responsibility of every citizen of the Earth. It’s within everyone’s power to prevent unnecessary waste of resources and cut down pollution. Buy with discretion; use with care what you own to prolong its lifespan. In this way, it’s not difficult to reduce your fashion footprint.