By Yeh Tzu-hao

Translated by Wu Hsiao-ting

Photos by Yu Zi-cheng

A decade ago in Türkiye, Tzu Chi volunteers began offering Syrian refugee children a chance at education. From their once pale and hopeless faces, dreams of becoming doctors, engineers, architects, and teachers began to blossom—a testament to the power of education to transform lives.

At the September 2024 graduation ceremony for El Menahil International School’s high school division, teachers and students gather for a group photo to mark this significant milestone. For graduates who gain university admission but face financial difficulties, Tzu Chi offers support to help them complete their studies. Mustafa Hamwieh

On December 8, 2024, after more than 13 years, the Syrian civil war showed signs of ending. While uncertainty remained, many Syrians began returning home from neighboring countries like Türkiye and Lebanon.

In Sultangazi, Istanbul Province, Türkiye, a group of Syrians was also preparing for a homecoming of sorts—but not to Aleppo, Homs, or Damascus. The “homecoming” in this instance was to Taiwan, 8,000 kilometers (4,970 miles) away. Faculty members and graduates of El Menahil International School—founded by Tzu Chi to support Syrian refugees—were journeying to their spiritual home. During their visit, they would receive their volunteer certification from Dharma Master Cheng Yen.

Upon their arrival at Tzu Chi’s Banqiao campus in New Taipei City, the group was warmly welcomed at the entrance by Faisal Hu (胡光中), head of Tzu Chi Türkiye. As a new beginning dawned in Syria, Hu greeted them with a powerful message: “You are no longer refugees!” His words struck a deep chord—many were overcome with emotion, some even moved to tears, as they reflected on the years they had spent in exile due to the war.

Struggles in a foreign land

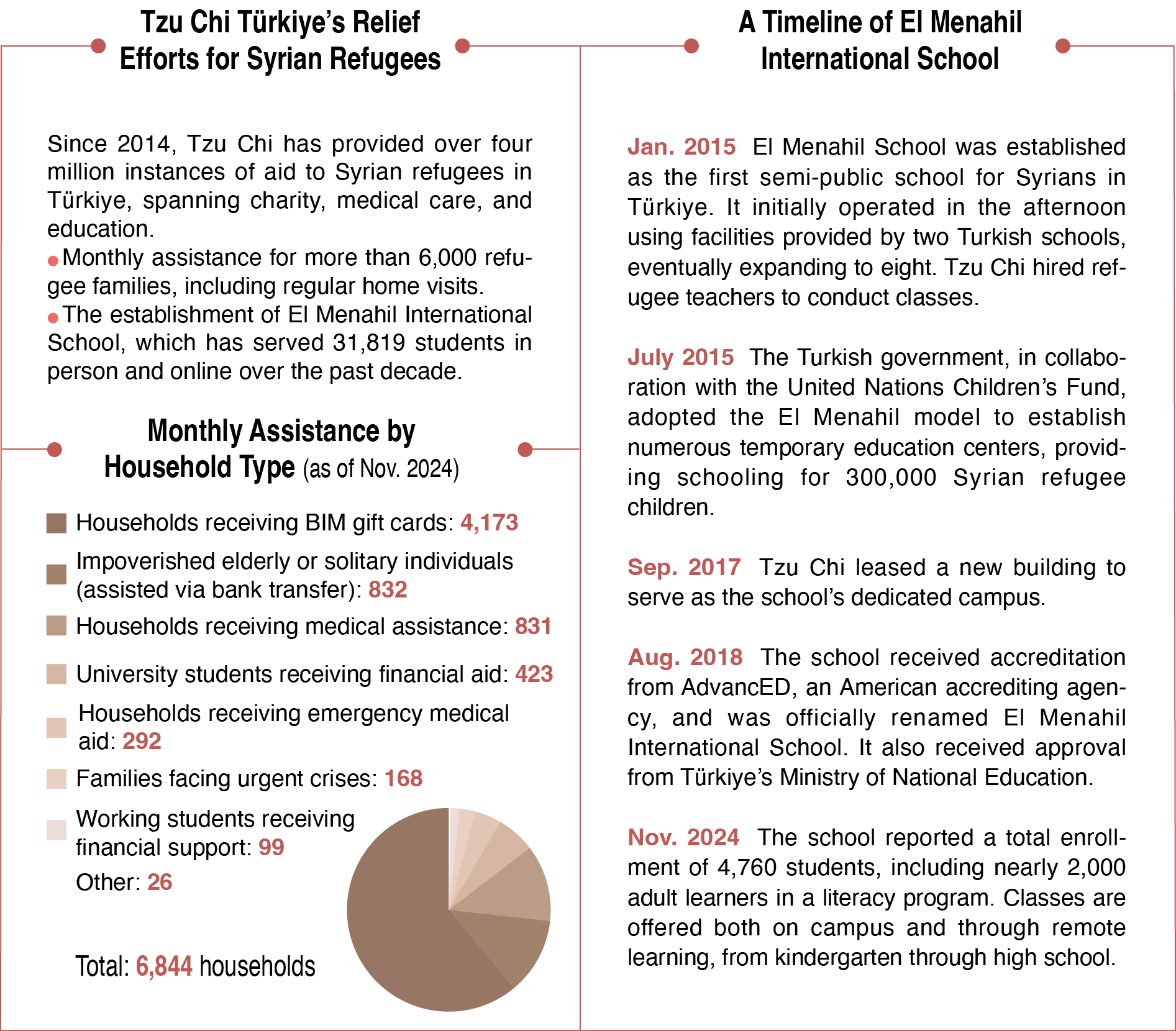

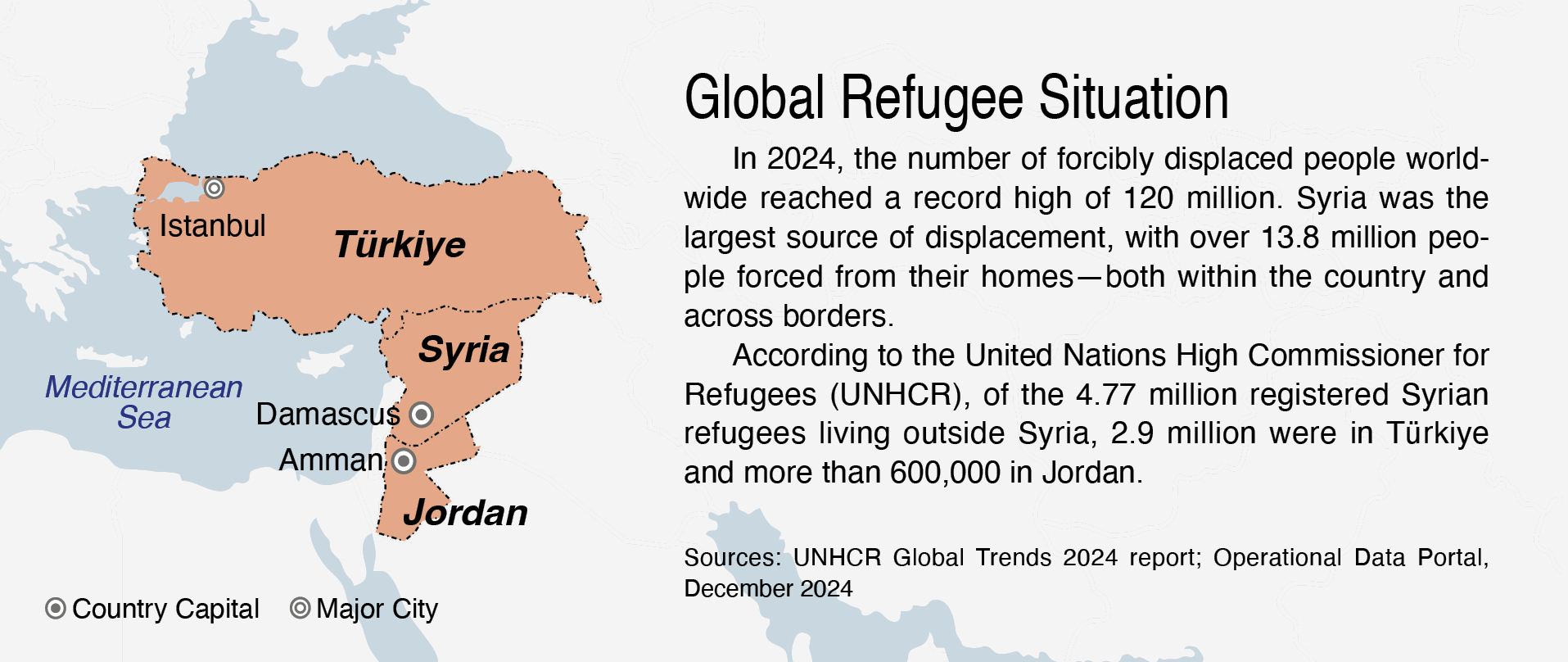

The war’s airstrikes, shelling, and other forms of violence over the years had forced millions of Syrians to flee. By the end of 2024, over 4.77 million Syrians were still registered as refugees, according to the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. About 60 percent of them were in Türkiye, while the rest were spread across Lebanon, Jordan, Iraq, Egypt, and other North African countries.

For Syrians who fled to neighboring Arab countries like Lebanon and Jordan, life as refugees was difficult, but at least language wasn’t a barrier. As a result, children were more easily integrated into local education systems. Refugees in Türkiye, however, faced greater challenges. The country uses modern Turkish, written in the Latin alphabet, making it harder to adjust to a linguistically and culturally distinct environment.

Due to language barriers and regulatory challenges, many Syrian refugees in Türkiye, despite having professional qualifications in fields like teaching or healthcare, were unable to continue their careers. Instead, they were often forced into low-skilled, low-paying jobs. In Istanbul Province, host to over half a million Syrian refugees, many garment and shoe factories employed Syrians to reduce operational costs.

“I worked as a sewing machine operator, earning about 500 U.S. dollars a month,” recalled Kamil Hatib, now a teacher at El Menahil International School. “But children aged 12 to 14, working over ten hours a day, earned only 150 to 200 U.S. dollars.” Employers preferred hiring cheap child labor, subjecting young workers to conditions that even adults could hardly endure. “Some worked 13 hours a day with only 13 minutes of rest and were often scolded by their bosses!” said Faisal Hu, his heart going out to the children.

Even when parents wanted to send their children to school, significant obstacles remained. International and private schools offering Arabic-language instruction were expensive, while Turkish public schools, though more affordable, didn’t teach Arabic. As a result, children attending these schools risked losing their native language. “Education for our children was the greatest challenge we faced,” said Hatib.

In 2015, while visiting Syrian refugee families, Tzu Chi volunteers saw out-of-school refugee children selling bottled water outside a subway station to help support their families.

Ali Kord Arabo, then 11 years old, worked in a shoe factory before Tzu Chi’s assistance enabled him to enroll at El Menahil School.

A father’s plea

Establishing a school wasn’t part of the plan when Tzu Chi volunteers first began assisting Syrian refugees in Türkiye. In 2014, volunteers began by focusing on the immediate needs in Sultangazi, a district of 600,000 where tens of thousands of refugees were struggling to survive. Following Tzu Chi’s charitable aid model, volunteers conducted home visits, compiled recipient rosters, and distributed aid.

But during one distribution, a refugee tried to sell back the blankets and food he had just received. Faisal Hu, one of the volunteers, was confused and frustrated—until he heard the man’s explanation: “Our children can’t go to school. If you have money, please give us money so they can get an education!”

That plea became a turning point. It helped inspire the founding of El Menahil. At the time, Tzu Chi had only three volunteers in Türkiye: Faisal Hu, his wife, Nadya Chou (周如意), and Yu Zi-cheng (余自成). Determined to help Syrian children access education, they walked the streets of Sultangazi and Arnavutköy to identify children who were out of school. They then sent the collected data to Tzu Chi’s headquarters in Taiwan for evaluation.

El Menahil opened in January 2015 in Sultangazi, enrolling 587 students from first to seventh grade. “Master Cheng Yen said, ‘We’ll provide subsidies equal to the children’s wages so they can study instead of work,’” Chou recalled. At first, many Syrian parents didn’t believe it, but Chou, Hu, and Yu worked hard to bring Tzu Chi’s commitment into reality.

Tzu Chi partnered with the Sultangazi government to establish the school. It operated initially within public Turkish school buildings in the afternoons, with refugee teachers using Syrian textbooks. Tzu Chi covered the teachers’ salaries and other expenses.

Mohammed Nur Alhajjar, who started at El Menahil as a student in first grade and later graduated from its high school division, was the first student to arrive on the school’s opening day in January 2015. After walking 40 minutes from home, he stood by the gate, waiting for it to open. When volunteer Yu asked why he had come so early, young Alhajjar replied in broken Turkish: “I was afraid that if I arrived too late, I wouldn’t have a seat.”

In 2017, the school moved into a rented building, providing students with a permanent place to learn. The following year, it earned accreditation from AdvancED, an American accrediting agency, and was renamed El Menahil International School. Today, it is a large, comprehensive institution offering kindergarten through high school programs, as well as adult literacy classes. By late 2024, it had an enrollment of over 4,700 students, both in-person and online. Five hundred and thirty-one students had graduated from high school, and 377 had gone on to pursue university studies—146 in medical fields, 177 in science and engineering, and 54 in social sciences, including languages, religion, and media.

Among the graduates of the school is Ahmad Jned, a prime example of the transformative power of education. Jned fled to Türkiye in 2014 at age 17, bringing his high school textbooks and exam papers in hopes of continuing his studies. However, financial hardship forced him to work in a shoe factory. In 2017, he found a second chance at El Menahil.

“Tzu Chi took me from the factory to school, and my heart changed from one filled with hatred to one filled with love,” Jned shared. “Those who haven’t experienced this can’t truly understand.” Seizing the opportunity, he worked hard to catch up on his education. After graduating from El Menahil, he was accepted into one of the world’s top 500 technical universities, where he graduated with honors. When he received his first paycheck, he donated it to Tzu Chi to support Ukrainian refugees. Now, he is preparing to start his own business.

“Jned hopes to one day repay all the financial aid he received from Tzu Chi,” volunteer Hu said. Seeing refugee children complete their education and go on to succeed brings him immense satisfaction. He never expected anything in return for helping these children, but witnessing their transformation fills him with great joy.

Hu recalled that when he first met these children and asked what they wanted to be, they had no expectations. But things changed after they began studying at El Menahil. “I want to be a doctor or nurse to help those suffering from war,” some children said. Others shared, “I want to be an engineer or architect to rebuild my homeland,” or “I want to be a teacher to help children who can’t go to school.”

“This is the true power of education,” Hu affirmed.

A Syrian child shows respect to volunteer Faisal Hu by kissing his hand during his visit to her family.

Volunteer Nadya Chou says goodbye to the children of a Syrian refugee family living in an underground apartment after her visit.

From exile to empowerment

The name “Menahil” means “spring of water” in Arabic. It was chosen to symbolize a wellspring of knowledge for children trapped in an educational desert. Though the school was established to support Syrian refugee children, it has also brought indirect benefits to Turkish society.

Ali Uslanmaz, former mayor of Sultangazi and now an advisor to Tzu Chi Türkiye, remarked that if Syrian refugee children were unable to receive an education, they would certainly struggle growing up. Once marginalized, they would be more likely to fall into alcoholism, drug addiction, or violence, posing a risk to society.

Following the outbreak of the Syrian civil war, more than 500,000 refugees arrived in Istanbul. Without access to education, many children ended up on the streets or working illegally, heightening tensions with locals and raising concerns among both the government and the public. In contrast, Syrian children were rarely seen wandering the streets in Sultangazi, home to El Menahil. Cases of child labor and interethnic conflict were also significantly lower than in other areas. “Without El Menahil, it would have been a disaster,” said teacher Hatib.

At El Menahil, students can study in peace. They learn core subjects in their native language, including Arabic, social studies, mathematics, physics, and biology. The school also offers courses in Turkish, English, and Chinese. Just as important is its emphasis on religious education, as well as humanistic education rooted in Tzu Chi’s core values of compassion, gratitude, respect for all life, and a spirit of service. In addition to studying the Quran, students can take elective courses on these values as part of Tzu Chi’s cultural curriculum.

In 2023, Tzu Chi, in collaboration with National Taiwan Normal University (NTNU), Tzu Chi University, and the Tzu Chi International Youth Association, launched the Menahil Promise—Syrian Refugee Chinese Learning Support Program. Led by Assistant Professor Hu Cui-jun (胡翠君) from NTNU’s College of Education, the initiative recruits young volunteers to teach Chinese to El Menahil students through online lessons.

Volunteer Chou strongly advocates for Chinese language education, recognizing the value of multilingualism. “Students at El Menahil once had no access to education. Now, they can learn Arabic, Turkish, English, and even Chinese. Imagine what a transformation this is for them! If they pass the Chinese proficiency exam, they can earn a certificate issued by Taiwan’s Ministry of Education, giving them more opportunities for further studies or future employment.”

Chou also introduces Syrian students to the arts of tea ceremony and flower arrangement. Her husband, Hu, didn’t quite agree with her devotion to these arts at first—until she handed him a letter from one of her students.

“She couldn’t read Arabic and asked me to translate it,” Hu recounted. “One sentence struck me deeply: ‘I am so grateful to you. You treat me like a mother would, seeing me as an ordinary child—just like any other.’”

At that moment, Hu realized his mistake. These children were not born as refugees. They were individuals who had lost their normal lives to war, yet were often reduced to a label.

“In times of war and chaos, survival becomes the priority,” Chou explained. “But bringing beauty into their lives is just as important.” She believes that these moments of beauty can heal, provide comfort, and even help the children navigate future challenges.

From gratitude to action

Master Cheng Yen’s vision for El Menahil is deeply rooted in compassion: “Instead of allowing children fleeing conflict to harbor resentment, we must plant seeds of love and gratitude within them.”

Helping students and teachers fully heal from the psychological trauma of war and displacement—and let go of the sorrow and anger caused by war crimes—is no easy task. However, one thing is certain: over the past decade, seeds of love and care have taken root in their hearts and begun to flourish.

El Menahil students and teachers frequently extend a helping hand, donating to Tzu Chi to support disaster survivors and others in need. This spirit of giving was especially evident in February 2023, when a powerful 7.8-magnitude earthquake struck southern Türkiye and northern Syria. The school’s faculty and alumni actively volunteered in hard-hit areas, becoming a vital part of Tzu Chi’s disaster relief efforts.

“Receiving Tzu Chi’s support inspired me to help others,” said Ahmed Aliyan, a Syrian and deputy principal of El Menahil. He arrived in Türkiye in 2015 with his wife and six children, and received four thick blankets from Tzu Chi, which helped his family endure the harsh winter. Once his life stabilized, he did his best to give back, caring for fellow refugees in Istanbul and later traveling to Beirut, Lebanon, in late 2020 to assist with aid distributions following the Port of Beirut explosion. When the 2023 earthquake struck, he once again stepped forward without hesitation.

“We told the earthquake survivors in Türkiye, ‘You have stood with us Syrians for ten years. Now it’s our turn to support you. Let’s work together—we are one family,’” Aliyan said.

Among those who joined Tzu Chi’s earthquake relief efforts was Muhammad Hak, then a high school student at El Menahil. He captured a poignant moment of a fellow Syrian volunteer embracing a survivor, a photo later chosen as the cover image for the 677th issue of Tzu Chi Monthly, which reported on the earthquake. Seeing El Menahil students and graduates take on the role of documenting Tzu Chi’s relief work filled their mentor, volunteer Yu, with deep satisfaction. “Before, they were the ones being documented,” said Yu. “But during the 2023 earthquake, they became the ones documenting Tzu Chi’s work.”

As a gesture of gratitude, faculty and students at El Menahil often donate to Tzu Chi to support Taiwan after disasters (photo 1). During COVID-19, they once again contributed, helping Tzu Chi headquarters in Taiwan purchase vaccines to accelerate the island’s vaccination program. Ali Al-Aboudi, then a second grader, donated his cherished one-euro coin, writing, “This coin is precious to me because it holds a memory, but those in need are more precious” (photo 2). Mohammed Nimr Aljamal

At the end of 2024, a group of faculty members and graduates of El Menahil International School visited Taiwan to receive their volunteer certification from Dharma Master Cheng Yen. They are pictured here at Tainan Tzu Chi Senior High School, which had signed a memorandum of cooperation with El Menahil. Huang Xiao-zhe

Standing by them

In alignment with the United Nations’ 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), El Menahil International School not only provides free, equitable, and quality elementary and secondary education for vulnerable refugee children—fulfilling SDG 4, “Quality Education”—but also fosters values of love, peace, and non-violence. Volunteers’ efforts to bring children out of factories and into classrooms directly supports SDG 8, “Decent Work and Economic Growth,” and SDG 16, “Peace, Justice, and Strong Institutions,” by addressing child labor and the broader need for social stability.

For those involved, the mission is not only to educate but also to offer a sense of direction and hope in uncertain times. “I hope to carry forward the spirit I’ve learned from Tzu Chi,” said Kerem Tahiroglu, a teacher at El Menahil. “I want to spread it to places where it’s still unknown—especially in the turbulent Arab world.” After receiving his volunteer certification personally from Master Cheng Yen, he pledged to spread Great Love—an unconditional love that embraces all of humanity—and to help relieve suffering. The Syrian volunteers certified alongside him share the same aspiration: to one day return to Syria and rebuild their homeland with love.

“I tell them, ‘If one day you see me and Nadya strolling across a square in Aleppo, come and take us to visit your home,” said volunteer Hu. He had repeated this line countless times during aid distributions for Syrian refugees as words of encouragement, a way to offer hope and lift their spirits. But now, that “dream” no longer feels so distant.

“No one knows what the future holds for Syria, or what life will be like in six months or a year,” Hu continued. “This uncertainty makes many Syrians anxious. During this time, our role is to stand by the teachers and students of El Menahil. Our promise is to support them as they find their way home.”