By Yeh Tzu-hao

Translated by Wu Hsiao-ting

Photos by Hsiao Yiu-hwa

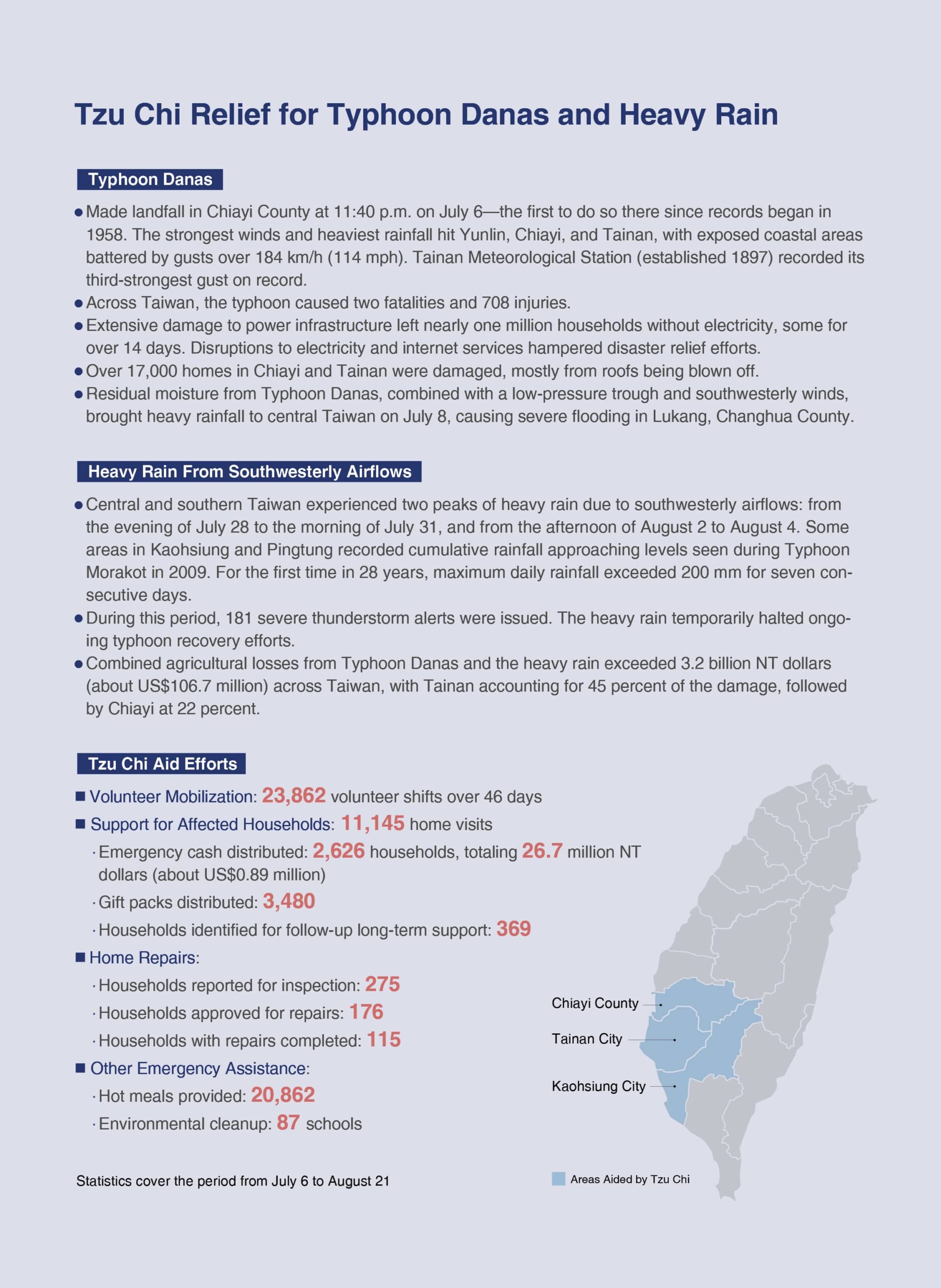

Can the goals of naturally-grown safe crops, sustained soil fertility, and fair returns for farmers truly coexist as climate change lowers yields and pesticide overuse degrades the land? The United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goal 15 calls for protecting ecosystems, preserving biodiversity, and preventing land degradation. For over a decade, Tzu Chi has been working to help make this vision a reality in eastern Taiwan.

Chen Sheng-hua (陳生華) and his wife, You Rui-zhen (游叡臻), natural farmers in Fenglin, Hualien, eastern Taiwan, are members of a Tzu Chi-supported crop production and marketing team. With guidance from Tzu Chi University faculty, they have improved their farming techniques and strengthened the resilience of their fields.

In addition to majestic mountains and expansive, beautiful plains, Taiwan’s Hualien and Taitung regions are also blessed with rich, fertile land. Agriculture has long been a vital pillar of the eastern region’s economy. But as industrialization and urbanization have progressed, many young people have moved to Taiwan’s more prosperous western region in search of work, leaving behind aging elders and increasing stretches of fallow farmland. How can local agriculture be revitalized—creating greater value, providing stable income for farmers, and drawing young people back home to farm? Tzu Chi’s charity and education missions have been working together on this challenge for years.

Eco-friendly farming

Tzu Chi’s commitment to agriculture began with concerns about climate change and potential food crises. In 2010, the foundation leased 20 hectares (50 acres) of land in Zhixue Village, Shoufeng Township, Hualien County. This opportunity came about when Taiwan Sugar Corporation, having reduced domestic sugarcane production in favor of imported raw materials, began offering large tracts of idle farmland for lease. It was on this plot that Tzu Chi established Zhixue Great Love Farm as a model for charity-based farming, with various crops grown on a trial basis.

In 2016, the leased area was reduced to 12 hectares and was taken over by the Jing Si Abode, the Buddhist convent founded by Dharma Master Cheng Yen. The harvest of the farm now helps sustain the Abode’s daily needs and supports charity efforts, including local relief and international disaster aid.

Volunteers from across Taiwan cooperate to work the land—preparing fields, clearing irrigation channels, and using organic rice-farming methods. They control pests using non-toxic biological formulations and manually weed instead of using herbicides. For more than eight years, Zhixue Great Love Farm has not only yielded clean, toxin-free rice but has also seen its surrounding ecosystem thrive.

“We farm organically from start to finish, and the environment has flourished,” said volunteer Ye Li-qing (葉麗卿), who manages the farm’s administrative affairs. “In April, you can see fireflies. We’ve also seen wild boars, Reeves’s muntjacs, and snakes.” She recalled a time when a mother boar and her piglets wandered into the fields, a clear sign of successful land conservation efforts, prompting volunteers to install fencing.

But Tzu Chi’s involvement in the area extends beyond merely tending to the Great Love Farm. The foundation has also recognized that many farmers in Hualien could benefit from some support. “Farming is not easy,” noted Lu Fang-chuan (呂芳川), director of Tzu Chi’s Department of Charity Mission Development. Many fields in Hualien have been left idle, he explained, while those still farming often lack the tools, techniques, and other resources needed to succeed. These challenges, coupled with their unfamiliarity with modern sales channels, have made it difficult for many farmers to earn a profit.

To help address these issues, Tzu Chi has partnered with the Hualien District Agricultural Research and Extension Station and the Hualien County Government’s Agriculture Department. Since 2013, they have supported farmers in five Indigenous townships—Xiulin, Wanrong, Guangfu, Fengbin, and Zhuoxi—by helping them form crop production and marketing teams.

The initiative has introduced high-value crops, like Inca nuts, and improved cultivation techniques for crops such as red quinoa. At the same time, it has guided farmers in a transition away from conventional agricultural methods to more sustainable and eco-friendly practices. Instead of using pesticides, chemical fertilizers, and herbicides, they now farm in greater harmony with nature and the land’s capacity.

“Hualien and Taitung have the cleanest soil, water, and air in Taiwan,” Lu said. “Our first priority is revitalizing local farmland. The next goal is to bring young people back to farming and reverse the trend of skipped-generation households, in which grandparents are raising grandchildren in the absence of their adult children.” He added that by returning home, young people can avoid the high living costs of city life, be their own boss, and build a meaningful future in their hometown.

Tzu Chi volunteers are committed to using organic farming methods at Zhixue Great Love Farm. Shi De Qian

Support from the education mission

While Tzu Chi’s charity mission has offered strong support, its education mission has also assisted farmers in many areas, including farming techniques, product processing, and marketing.

“In 2011, some students expressed interest in doing service learning at Zhixue Great Love Farm, which led us to connect with Director Lu from the Charity Mission Development Department,” said Professor Chiang Yun-chih (江允智), director of the Sustainable Development Office at Tzu Chi University (TCU) in Hualien. At the time, the university already had faculty engaged in environmental sustainability and eco-friendly farming research and had established connections with local practitioners of non-toxic, organic agriculture. After helping students connect with the farm, faculty also began collaborating with Tzu Chi’s farming team.

Back then, Tzu Chi University and the Tzu Chi University of Science and Technology (TCUST), also in Hualien, were separate institutions. (A merger of the two would be completed in 2024.) Faculty and students at TCUST took a different route into charity-based farming. In 2013, Professors Liu Wei-chung (劉威忠) and Keng Nien-tzu (耿念慈), both of the Department of Medical Imaging and Radiological Sciences, led students to form the Huayu Club, which grew medicinal herbs and flowers. The club also produced small quantities of crops to supplement the diets of financially disadvantaged students.

The university allocated a plot of land near the dormitories for the club to cultivate, but the soil was rocky—hoes would strike stones immediately, and even cassava, a hardy crop whose tuberous roots usually grow downward into the ground, grew sideways across the surface. Tzu Chi volunteer Xu Wen-long (徐文龍), who had a background in construction, brought in heavy machinery to help remove the rocks and prepare the land, which was then named Blessings Farm. What began as a student horticulture club gradually evolved into an agricultural biomedical research and development effort.

Red quinoa, which is relatively easy to grow and can be harvested within three to four months, became a focus. Faculty and students made notable strides in its cultivation and processing. After Typhoon Nepartak struck Taitung in July 2016, Master Cheng Yen tasked TCUST with helping affected farmers by offering courses on red quinoa cultivation, processing, and marketing. Professors Liu and Keng led cultivation and processing training, while Professors Chen Hwang-yeh (陳皇曄) and Kuo Yu-ming (郭又銘) from the Marketing and Distribution Management Department provided instruction on marketing and distribution.

In addition to red quinoa, the agricultural biomedical team visited several Indigenous villages to study traditional crops and wild edibles, such as star jelly (Nostoc commune), the branched string lettuce (Ulva prolifera), and bird’s-nest fern (Asplenium nidus), a vegetable favored by both Indigenous and Han communities. The team identified and developed new uses for these wild edibles beyond eating them directly.

For more than a decade, TCUST faculty and students helped farmers in Hualien and Taitung, as well as agricultural biotech companies, solve technical challenges. At the same time, the university produced skilled graduates ready to enter the workforce. “Our students were willing to get their hands dirty,” said Professor Liu, with pride. “It was amazing to see them one moment wearing conical hats and picking stones in the fields, and the next operating precision instruments in a lab. This kind of hands-on experience gave them a deep understanding of both the crops and the conditions in which they grow. Many companies wanted to recruit our graduates—so much so, there weren’t enough to meet the demand!”

Tzu Chi University faculty and students (photo 1) take part in harvesting star jelly in the Jiamin tribal settlement. Professor Vivian Tien (photo 2) from the Department of Foreign Languages and Literature teaches young farmers how to introduce their agricultural products in English, helping them expand marketing channels for their high-quality produce (photo 3). Courtesy of Tzu Chi University

Carbon reduction

A collaborative system gradually took shape in the agricultural sector when TCU and TCUST joined forces with the Tzu Chi charity mission. The Tzu Chi Foundation led charity-based farming efforts by supplying farmers with machinery, seedlings, and other supplies, while TCUST’s agricultural biomedical team, drawing on its strong research and development background, took on the role of guiding product processing and marketing.

Meanwhile, TCU responded to the Ministry of Education’s call for universities to fulfill their University Social Responsibility (USR) by establishing a USR Center. The center’s mission is to support local communities in solving real-world challenges and to promote regional revitalization through sustainable agricultural practices and economic models.

In 2024, TCU made its debut at the USR Awards, hosted by Global Views Monthly. Its project—Satoyama United Carbon Economy: Local Practice of Sustainable Consumption and Production—received the Model Award in the Ecological Co-Prosperity Category.

The term “Satoyama,” which originated in Japan, broadly refers to a mosaic of natural and human-managed landscapes—such as hills, forests, fields, grasslands, homes, ponds, and streams—where people live in harmony with nature. This concept closely reflects the geography and traditional way of life in Hualien, making it an ideal framework for TCU’s social responsibility work. For this reason, the university’s USR Center incorporated Satoyama into the project’s name.

“We’re currently promoting low-carbon and natural farming methods,” explained Professor Chiang Yun-chih, who also serves as the project lead at the USR Center. “Once these practices are well established, the entire farmland ecosystem and its biodiversity will improve.” He noted that the 4 per 1000 Initiative, introduced at the Paris climate conference in 2015, proposes that increasing soil organic carbon by 0.4 percent annually could help halt the rise in atmospheric CO₂ levels. This underpins the carbon economy, which offers economic benefits to farmers who adopt sustainable practices.

“We guide farmers in adopting organic or natural farming methods and applying circular economy principles by returning agricultural waste to the soil,” Chiang added. “We then regularly test for increases in soil organic carbon.”

He went on to emphasize that there is now a global consensus on the value of carbon reduction. If farmers can provide credible data showing how much greenhouse gas emissions they’ve reduced, they can sell the resulting carbon credits to businesses seeking to offset their own emissions. In essence, they can generate income through soil carbon sequestration—the more carbon stored in the soil, the greater the profit.

At present, TCU’s USR team is working with rice farmers on a “low-carbon rice” cultivation experiment, tracking carbon emissions from planting to harvest to explore its potential in the carbon economy. Yet, no matter how diligently farmers work to reduce emissions and improve their practices, they still need to sell quality crops to earn a sustainable income.

To help address this need, TCU’s USR team has developed sales channels for farmers. In 2018, several like-minded professors spearheaded the creation of the Sustainable Food Consumption Cooperative at TCU, providing a platform for small farmers to sell their crops and processed foods directly on campus.

“In simple terms, it’s about keeping money flowing locally rather than letting it leave the community,” said Professor Chiu Yie-ru (邱奕儒), one of the cooperative’s founders. The cooperative is jointly invested in and operated by faculty, students, and volunteers. Every member has a say in its operations and can use their purchasing power to support local agriculture and the rural economy.

Professor Chiu explained the cooperative’s criteria for selecting products to sell: “We prioritize organic and environmentally friendly products, especially those grown locally in Hualien. We also make a special effort to support items from local farmers’ cooperatives.”

Beyond selling produce at the campus store, TCU hosts a monthly small farmers’ market, giving farmers another opportunity to showcase and sell their foodstuffs.

“Who you buy from determines where your money ultimately goes,” said Professor Hsieh Wan-hua (謝婉華) of TCU’s Department of Public Health, who is also associate chair of the cooperative. “We aim to support sustainable production through responsible consumption.”

By emphasizing value over price, the university’s effort fosters a win-win scenario for consumers, producers, and the broader community. In doing so, it brings the ideals of the Satoyama United Carbon Economy into everyday life.

From cultivation to innovation

It has been 12 years since Tzu Chi began working in the five Indigenous townships mentioned earlier in the article, providing farmers with seedlings, supplies, and guidance on cultivation, processing, and sales. Over the years, the foundation and Tzu Chi University have built strong ties with local farmers, who in turn have welcomed faculty and students into their fields for hands-on learning and offered students part-time job opportunities.

“Last year, we collaborated with Professor Vivian Tien [田薇] from TCU’s Department of Foreign Languages and Literature,” said Lin Xiu-ying (林秀瑛), a young farmer of the Taroko Indigenous group from the Jiamin tribal settlement in Xincheng Township. “She brought her students to help us practice giving farm tours and product introductions in English. She also helped us recruit students for paid internships through a school-industry partnership. When foreign visitors come, they serve as our English-speaking guides and interpreters.”

Lin recalled how her connection with Tzu Chi began. In the 1990s, bird’s-nest fern became a popular crop in Jiamin. At its peak, it sold for 230 New Taiwan dollars (US$7.70) per catty (600 grams). Its profitability drew many villagers to start growing it. But lacking marketing know-how and an understanding of market dynamics, they were exploited by middlemen offering them much lower prices. Eventually, when the price dropped to just 15 dollars per catty, many villagers gave up, feeling it was no longer worth the effort. Fortunately, things began to turn around as younger people who had returned to their hometown established direct sales channels with restaurants and hotels, securing better prices for farmers and restoring the crop’s viability.

Beyond the economic context, bird’s-nest fern posed another challenge: It begins to wilt and darken within two or three days of harvest, limiting its shelf life and making storage and transportation difficult. To overcome this, younger farmers in Jiamin sought help from TCUST’s agricultural biomedical team. Professors Liu Wei-chung and Keng Nien-tzu led students in developing a method to process the fern into powder. This innovation paved the way for a range of processed products, including Jiamin’s signature treats: bird’s-nest fern nougat, cookies, and ice cream.

Yet more challenges lay ahead. In 2020, the COVID-19 pandemic dealt a heavy blow to Hualien’s tourism industry, leaving local leisure farms largely empty. Despite the setback, Jiamin’s younger farmers continued working with faculty from TCU and TCUST to improve their farming practices. For example, under the guidance of Professor Chiu Yie-ru, they replaced black shade nets with natural tree cover, adopting more environmentally friendly and sustainable methods for growing bird’s-nest fern.

Tourism began to recover in 2023, but fresh challenges weren’t far behind. The April 3, 2024 earthquake and Typhoon Kong-rey caused serious damage, including widespread destruction of bird’s-nest fern fields, and once again led to a steep drop in tourist numbers. Despite the adversity, the younger farmers in Jiamin remained committed to their work—with Tzu Chi faculty standing by their side.

Lin shared that after the earthquake, Tzu Chi professors encouraged them to use the lull in tourism to build skills and develop new products. “Professors Liu and Keng are incredibly dedicated,” she said. “We reach out to them with questions all the time, so much so that I sometimes feel bad. But they’re always so patient and willing to help.” The gratitude in her voice was unmistakable.

Glossary: The 4 per 1000 Initiative

The 4 per 1000 Initiative was introduced at the 2015 United Nations Climate Change Conference, where the Paris Agreement was adopted. This initiative suggests that increasing the organic carbon content in the Earth’s soils by 0.4 percent each year could significantly offset greenhouse gas emissions caused by human activity.

Conventional farming practices, such as applying chemical fertilizers, spraying pesticides, and over-cultivating land, lead to the loss of organic carbon from soil into the atmosphere. In contrast, adopting more sustainable methods and restoring degraded land can help sequester carbon in the soil.

Food forest

Tzu Chi has promoted charity-based farming in Taiwan for over a decade, upholding eco-friendly principles that avoid the use of chemical fertilizers and pesticides. The journey has been one of continuous experimentation, learning, and adaptation—filled with the joys of harvest as well as unpredictable challenges brought on by natural disasters.

For example, members of a production and marketing team in Fengbin Township had been cultivating Inca nuts when a cold snap last winter caused their crops to wither en masse, unable to withstand the chill. In response, Tzu Chi provided camellia seedlings—another crop used for edible oil production—to help the farmers replant their fields and start anew.

In another initiative, following the merger of Tzu Chi University and the Tzu Chi University of Science and Technology, the combined institution has been actively involved in exploring and promoting “food forests.” Through its USR Center, the university transformed the Blessings Farm at its Jianguo Campus into a living laboratory, using seeds and saplings to build a food forest from the ground up. In collaboration with the school’s Continuing Education Office, the USR Center also launched a related course titled “The Way of Resilient Farming: From Stones to Forests,” which has drawn farmers from across Taiwan.

At Blessings Farm, German soil biology expert Tobias Neugebauer, a visiting instructor, explained that building a food forest begins with nourishing the soil. Crops are then planted according to their growth patterns and functions, forming layers of vegetation—low, medium, tall, and emergent. This approach integrates a mix of cash crops and supportive plants, such as tall, hardy trees that provide protection from wind and intense sunlight.

“When typhoons strike, strong trees stay standing while weaker ones fall and decompose, becoming nutrients for the others. That’s what we’re trying to do here,” Neugebauer said. He emphasized that food forests still require human care, such as regularly pruning trees and allowing the fallen branches and leaves to return to the soil as organic matter. Over time, as the system matures, it becomes more self-sustaining and requires less intervention.

From the perspective of the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals, combining eco-friendly farming with sustainable economic models promotes not only environmental sustainability but also the resilience of urban and rural communities. Through the charity-based farming efforts of its charity and education missions, Tzu Chi is helping to produce clean, healthy food while also fostering mutual flourishing between people, communities, and the Earth. The dedicated efforts of volunteers, faculty, and farmers are already yielding promising results. Looking ahead, it is hoped that continued advancements in technology, concepts, and operational models will help Tzu Chi generate an even greater positive impact in eastern Taiwan and beyond, wherever the foundation is working in the future.

Tobias Neugebauer, a German soil biology expert and visiting instructor at Tzu Chi University’s USR Center, explains the structure of a food forest. In addition to food crops, it includes supportive plants that enrich the soil and provide shelter.

By Yeh Tzu-hao

Translated by Wu Hsiao-ting

Photos by Hsiao Yiu-hwa

Can the goals of naturally-grown safe crops, sustained soil fertility, and fair returns for farmers truly coexist as climate change lowers yields and pesticide overuse degrades the land? The United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goal 15 calls for protecting ecosystems, preserving biodiversity, and preventing land degradation. For over a decade, Tzu Chi has been working to help make this vision a reality in eastern Taiwan.

Chen Sheng-hua (陳生華) and his wife, You Rui-zhen (游叡臻), natural farmers in Fenglin, Hualien, eastern Taiwan, are members of a Tzu Chi-supported crop production and marketing team. With guidance from Tzu Chi University faculty, they have improved their farming techniques and strengthened the resilience of their fields.

In addition to majestic mountains and expansive, beautiful plains, Taiwan’s Hualien and Taitung regions are also blessed with rich, fertile land. Agriculture has long been a vital pillar of the eastern region’s economy. But as industrialization and urbanization have progressed, many young people have moved to Taiwan’s more prosperous western region in search of work, leaving behind aging elders and increasing stretches of fallow farmland. How can local agriculture be revitalized—creating greater value, providing stable income for farmers, and drawing young people back home to farm? Tzu Chi’s charity and education missions have been working together on this challenge for years.

Eco-friendly farming

Tzu Chi’s commitment to agriculture began with concerns about climate change and potential food crises. In 2010, the foundation leased 20 hectares (50 acres) of land in Zhixue Village, Shoufeng Township, Hualien County. This opportunity came about when Taiwan Sugar Corporation, having reduced domestic sugarcane production in favor of imported raw materials, began offering large tracts of idle farmland for lease. It was on this plot that Tzu Chi established Zhixue Great Love Farm as a model for charity-based farming, with various crops grown on a trial basis.

In 2016, the leased area was reduced to 12 hectares and was taken over by the Jing Si Abode, the Buddhist convent founded by Dharma Master Cheng Yen. The harvest of the farm now helps sustain the Abode’s daily needs and supports charity efforts, including local relief and international disaster aid.

Volunteers from across Taiwan cooperate to work the land—preparing fields, clearing irrigation channels, and using organic rice-farming methods. They control pests using non-toxic biological formulations and manually weed instead of using herbicides. For more than eight years, Zhixue Great Love Farm has not only yielded clean, toxin-free rice but has also seen its surrounding ecosystem thrive.

“We farm organically from start to finish, and the environment has flourished,” said volunteer Ye Li-qing (葉麗卿), who manages the farm’s administrative affairs. “In April, you can see fireflies. We’ve also seen wild boars, Reeves’s muntjacs, and snakes.” She recalled a time when a mother boar and her piglets wandered into the fields, a clear sign of successful land conservation efforts, prompting volunteers to install fencing.

But Tzu Chi’s involvement in the area extends beyond merely tending to the Great Love Farm. The foundation has also recognized that many farmers in Hualien could benefit from some support. “Farming is not easy,” noted Lu Fang-chuan (呂芳川), director of Tzu Chi’s Department of Charity Mission Development. Many fields in Hualien have been left idle, he explained, while those still farming often lack the tools, techniques, and other resources needed to succeed. These challenges, coupled with their unfamiliarity with modern sales channels, have made it difficult for many farmers to earn a profit.

To help address these issues, Tzu Chi has partnered with the Hualien District Agricultural Research and Extension Station and the Hualien County Government’s Agriculture Department. Since 2013, they have supported farmers in five Indigenous townships—Xiulin, Wanrong, Guangfu, Fengbin, and Zhuoxi—by helping them form crop production and marketing teams.

The initiative has introduced high-value crops, like Inca nuts, and improved cultivation techniques for crops such as red quinoa. At the same time, it has guided farmers in a transition away from conventional agricultural methods to more sustainable and eco-friendly practices. Instead of using pesticides, chemical fertilizers, and herbicides, they now farm in greater harmony with nature and the land’s capacity.

“Hualien and Taitung have the cleanest soil, water, and air in Taiwan,” Lu said. “Our first priority is revitalizing local farmland. The next goal is to bring young people back to farming and reverse the trend of skipped-generation households, in which grandparents are raising grandchildren in the absence of their adult children.” He added that by returning home, young people can avoid the high living costs of city life, be their own boss, and build a meaningful future in their hometown.

Tzu Chi volunteers are committed to using organic farming methods at Zhixue Great Love Farm. Shi De Qian

Support from the education mission

While Tzu Chi’s charity mission has offered strong support, its education mission has also assisted farmers in many areas, including farming techniques, product processing, and marketing.

“In 2011, some students expressed interest in doing service learning at Zhixue Great Love Farm, which led us to connect with Director Lu from the Charity Mission Development Department,” said Professor Chiang Yun-chih (江允智), director of the Sustainable Development Office at Tzu Chi University (TCU) in Hualien. At the time, the university already had faculty engaged in environmental sustainability and eco-friendly farming research and had established connections with local practitioners of non-toxic, organic agriculture. After helping students connect with the farm, faculty also began collaborating with Tzu Chi’s farming team.

Back then, Tzu Chi University and the Tzu Chi University of Science and Technology (TCUST), also in Hualien, were separate institutions. (A merger of the two would be completed in 2024.) Faculty and students at TCUST took a different route into charity-based farming. In 2013, Professors Liu Wei-chung (劉威忠) and Keng Nien-tzu (耿念慈), both of the Department of Medical Imaging and Radiological Sciences, led students to form the Huayu Club, which grew medicinal herbs and flowers. The club also produced small quantities of crops to supplement the diets of financially disadvantaged students.

The university allocated a plot of land near the dormitories for the club to cultivate, but the soil was rocky—hoes would strike stones immediately, and even cassava, a hardy crop whose tuberous roots usually grow downward into the ground, grew sideways across the surface. Tzu Chi volunteer Xu Wen-long (徐文龍), who had a background in construction, brought in heavy machinery to help remove the rocks and prepare the land, which was then named Blessings Farm. What began as a student horticulture club gradually evolved into an agricultural biomedical research and development effort.

Red quinoa, which is relatively easy to grow and can be harvested within three to four months, became a focus. Faculty and students made notable strides in its cultivation and processing. After Typhoon Nepartak struck Taitung in July 2016, Master Cheng Yen tasked TCUST with helping affected farmers by offering courses on red quinoa cultivation, processing, and marketing. Professors Liu and Keng led cultivation and processing training, while Professors Chen Hwang-yeh (陳皇曄) and Kuo Yu-ming (郭又銘) from the Marketing and Distribution Management Department provided instruction on marketing and distribution.

In addition to red quinoa, the agricultural biomedical team visited several Indigenous villages to study traditional crops and wild edibles, such as star jelly (Nostoc commune), the branched string lettuce (Ulva prolifera), and bird’s-nest fern (Asplenium nidus), a vegetable favored by both Indigenous and Han communities. The team identified and developed new uses for these wild edibles beyond eating them directly.

For more than a decade, TCUST faculty and students helped farmers in Hualien and Taitung, as well as agricultural biotech companies, solve technical challenges. At the same time, the university produced skilled graduates ready to enter the workforce. “Our students were willing to get their hands dirty,” said Professor Liu, with pride. “It was amazing to see them one moment wearing conical hats and picking stones in the fields, and the next operating precision instruments in a lab. This kind of hands-on experience gave them a deep understanding of both the crops and the conditions in which they grow. Many companies wanted to recruit our graduates—so much so, there weren’t enough to meet the demand!”

Tzu Chi University faculty and students (photo 1) take part in harvesting star jelly in the Jiamin tribal settlement. Professor Vivian Tien (photo 2) from the Department of Foreign Languages and Literature teaches young farmers how to introduce their agricultural products in English, helping them expand marketing channels for their high-quality produce (photo 3). Courtesy of Tzu Chi University

Carbon reduction

A collaborative system gradually took shape in the agricultural sector when TCU and TCUST joined forces with the Tzu Chi charity mission. The Tzu Chi Foundation led charity-based farming efforts by supplying farmers with machinery, seedlings, and other supplies, while TCUST’s agricultural biomedical team, drawing on its strong research and development background, took on the role of guiding product processing and marketing.

Meanwhile, TCU responded to the Ministry of Education’s call for universities to fulfill their University Social Responsibility (USR) by establishing a USR Center. The center’s mission is to support local communities in solving real-world challenges and to promote regional revitalization through sustainable agricultural practices and economic models.

In 2024, TCU made its debut at the USR Awards, hosted by Global Views Monthly. Its project—Satoyama United Carbon Economy: Local Practice of Sustainable Consumption and Production—received the Model Award in the Ecological Co-Prosperity Category.

The term “Satoyama,” which originated in Japan, broadly refers to a mosaic of natural and human-managed landscapes—such as hills, forests, fields, grasslands, homes, ponds, and streams—where people live in harmony with nature. This concept closely reflects the geography and traditional way of life in Hualien, making it an ideal framework for TCU’s social responsibility work. For this reason, the university’s USR Center incorporated Satoyama into the project’s name.

“We’re currently promoting low-carbon and natural farming methods,” explained Professor Chiang Yun-chih, who also serves as the project lead at the USR Center. “Once these practices are well established, the entire farmland ecosystem and its biodiversity will improve.” He noted that the 4 per 1000 Initiative, introduced at the Paris climate conference in 2015, proposes that increasing soil organic carbon by 0.4 percent annually could help halt the rise in atmospheric CO₂ levels. This underpins the carbon economy, which offers economic benefits to farmers who adopt sustainable practices.

“We guide farmers in adopting organic or natural farming methods and applying circular economy principles by returning agricultural waste to the soil,” Chiang added. “We then regularly test for increases in soil organic carbon.”

He went on to emphasize that there is now a global consensus on the value of carbon reduction. If farmers can provide credible data showing how much greenhouse gas emissions they’ve reduced, they can sell the resulting carbon credits to businesses seeking to offset their own emissions. In essence, they can generate income through soil carbon sequestration—the more carbon stored in the soil, the greater the profit.

At present, TCU’s USR team is working with rice farmers on a “low-carbon rice” cultivation experiment, tracking carbon emissions from planting to harvest to explore its potential in the carbon economy. Yet, no matter how diligently farmers work to reduce emissions and improve their practices, they still need to sell quality crops to earn a sustainable income.

To help address this need, TCU’s USR team has developed sales channels for farmers. In 2018, several like-minded professors spearheaded the creation of the Sustainable Food Consumption Cooperative at TCU, providing a platform for small farmers to sell their crops and processed foods directly on campus.

“In simple terms, it’s about keeping money flowing locally rather than letting it leave the community,” said Professor Chiu Yie-ru (邱奕儒), one of the cooperative’s founders. The cooperative is jointly invested in and operated by faculty, students, and volunteers. Every member has a say in its operations and can use their purchasing power to support local agriculture and the rural economy.

Professor Chiu explained the cooperative’s criteria for selecting products to sell: “We prioritize organic and environmentally friendly products, especially those grown locally in Hualien. We also make a special effort to support items from local farmers’ cooperatives.”

Beyond selling produce at the campus store, TCU hosts a monthly small farmers’ market, giving farmers another opportunity to showcase and sell their foodstuffs.

“Who you buy from determines where your money ultimately goes,” said Professor Hsieh Wan-hua (謝婉華) of TCU’s Department of Public Health, who is also associate chair of the cooperative. “We aim to support sustainable production through responsible consumption.”

By emphasizing value over price, the university’s effort fosters a win-win scenario for consumers, producers, and the broader community. In doing so, it brings the ideals of the Satoyama United Carbon Economy into everyday life.

From cultivation to innovation

It has been 12 years since Tzu Chi began working in the five Indigenous townships mentioned earlier in the article, providing farmers with seedlings, supplies, and guidance on cultivation, processing, and sales. Over the years, the foundation and Tzu Chi University have built strong ties with local farmers, who in turn have welcomed faculty and students into their fields for hands-on learning and offered students part-time job opportunities.

“Last year, we collaborated with Professor Vivian Tien [田薇] from TCU’s Department of Foreign Languages and Literature,” said Lin Xiu-ying (林秀瑛), a young farmer of the Taroko Indigenous group from the Jiamin tribal settlement in Xincheng Township. “She brought her students to help us practice giving farm tours and product introductions in English. She also helped us recruit students for paid internships through a school-industry partnership. When foreign visitors come, they serve as our English-speaking guides and interpreters.”

Lin recalled how her connection with Tzu Chi began. In the 1990s, bird’s-nest fern became a popular crop in Jiamin. At its peak, it sold for 230 New Taiwan dollars (US$7.70) per catty (600 grams). Its profitability drew many villagers to start growing it. But lacking marketing know-how and an understanding of market dynamics, they were exploited by middlemen offering them much lower prices. Eventually, when the price dropped to just 15 dollars per catty, many villagers gave up, feeling it was no longer worth the effort. Fortunately, things began to turn around as younger people who had returned to their hometown established direct sales channels with restaurants and hotels, securing better prices for farmers and restoring the crop’s viability.

Beyond the economic context, bird’s-nest fern posed another challenge: It begins to wilt and darken within two or three days of harvest, limiting its shelf life and making storage and transportation difficult. To overcome this, younger farmers in Jiamin sought help from TCUST’s agricultural biomedical team. Professors Liu Wei-chung and Keng Nien-tzu led students in developing a method to process the fern into powder. This innovation paved the way for a range of processed products, including Jiamin’s signature treats: bird’s-nest fern nougat, cookies, and ice cream.

Yet more challenges lay ahead. In 2020, the COVID-19 pandemic dealt a heavy blow to Hualien’s tourism industry, leaving local leisure farms largely empty. Despite the setback, Jiamin’s younger farmers continued working with faculty from TCU and TCUST to improve their farming practices. For example, under the guidance of Professor Chiu Yie-ru, they replaced black shade nets with natural tree cover, adopting more environmentally friendly and sustainable methods for growing bird’s-nest fern.

Tourism began to recover in 2023, but fresh challenges weren’t far behind. The April 3, 2024 earthquake and Typhoon Kong-rey caused serious damage, including widespread destruction of bird’s-nest fern fields, and once again led to a steep drop in tourist numbers. Despite the adversity, the younger farmers in Jiamin remained committed to their work—with Tzu Chi faculty standing by their side.

Lin shared that after the earthquake, Tzu Chi professors encouraged them to use the lull in tourism to build skills and develop new products. “Professors Liu and Keng are incredibly dedicated,” she said. “We reach out to them with questions all the time, so much so that I sometimes feel bad. But they’re always so patient and willing to help.” The gratitude in her voice was unmistakable.

Glossary: The 4 per 1000 Initiative

The 4 per 1000 Initiative was introduced at the 2015 United Nations Climate Change Conference, where the Paris Agreement was adopted. This initiative suggests that increasing the organic carbon content in the Earth’s soils by 0.4 percent each year could significantly offset greenhouse gas emissions caused by human activity.

Conventional farming practices, such as applying chemical fertilizers, spraying pesticides, and over-cultivating land, lead to the loss of organic carbon from soil into the atmosphere. In contrast, adopting more sustainable methods and restoring degraded land can help sequester carbon in the soil.

Food forest

Tzu Chi has promoted charity-based farming in Taiwan for over a decade, upholding eco-friendly principles that avoid the use of chemical fertilizers and pesticides. The journey has been one of continuous experimentation, learning, and adaptation—filled with the joys of harvest as well as unpredictable challenges brought on by natural disasters.

For example, members of a production and marketing team in Fengbin Township had been cultivating Inca nuts when a cold snap last winter caused their crops to wither en masse, unable to withstand the chill. In response, Tzu Chi provided camellia seedlings—another crop used for edible oil production—to help the farmers replant their fields and start anew.

In another initiative, following the merger of Tzu Chi University and the Tzu Chi University of Science and Technology, the combined institution has been actively involved in exploring and promoting “food forests.” Through its USR Center, the university transformed the Blessings Farm at its Jianguo Campus into a living laboratory, using seeds and saplings to build a food forest from the ground up. In collaboration with the school’s Continuing Education Office, the USR Center also launched a related course titled “The Way of Resilient Farming: From Stones to Forests,” which has drawn farmers from across Taiwan.

At Blessings Farm, German soil biology expert Tobias Neugebauer, a visiting instructor, explained that building a food forest begins with nourishing the soil. Crops are then planted according to their growth patterns and functions, forming layers of vegetation—low, medium, tall, and emergent. This approach integrates a mix of cash crops and supportive plants, such as tall, hardy trees that provide protection from wind and intense sunlight.

“When typhoons strike, strong trees stay standing while weaker ones fall and decompose, becoming nutrients for the others. That’s what we’re trying to do here,” Neugebauer said. He emphasized that food forests still require human care, such as regularly pruning trees and allowing the fallen branches and leaves to return to the soil as organic matter. Over time, as the system matures, it becomes more self-sustaining and requires less intervention.

From the perspective of the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals, combining eco-friendly farming with sustainable economic models promotes not only environmental sustainability but also the resilience of urban and rural communities. Through the charity-based farming efforts of its charity and education missions, Tzu Chi is helping to produce clean, healthy food while also fostering mutual flourishing between people, communities, and the Earth. The dedicated efforts of volunteers, faculty, and farmers are already yielding promising results. Looking ahead, it is hoped that continued advancements in technology, concepts, and operational models will help Tzu Chi generate an even greater positive impact in eastern Taiwan and beyond, wherever the foundation is working in the future.

Tobias Neugebauer, a German soil biology expert and visiting instructor at Tzu Chi University’s USR Center, explains the structure of a food forest. In addition to food crops, it includes supportive plants that enrich the soil and provide shelter.