By Chiu Chuan Peinn

Translated by Wu Hsiao-ting

Photos by Choong Keat Yee

Tzu Chi’s medical volunteers from Taiwan, Singapore, Malaysia, and the Philippines joined Cambodian teams to provide free medical care to thousands in need over a three-day clinic.

A surgeon taking part in a Tzu Chi free clinic held in Cambodia this past May operates on a patient to remove a tumor. Instead of a disposable surgical drape, white sterile wrapping paper from a surgical glove box was used—an environmentally conscious choice that reflects Tzu Chi’s values.

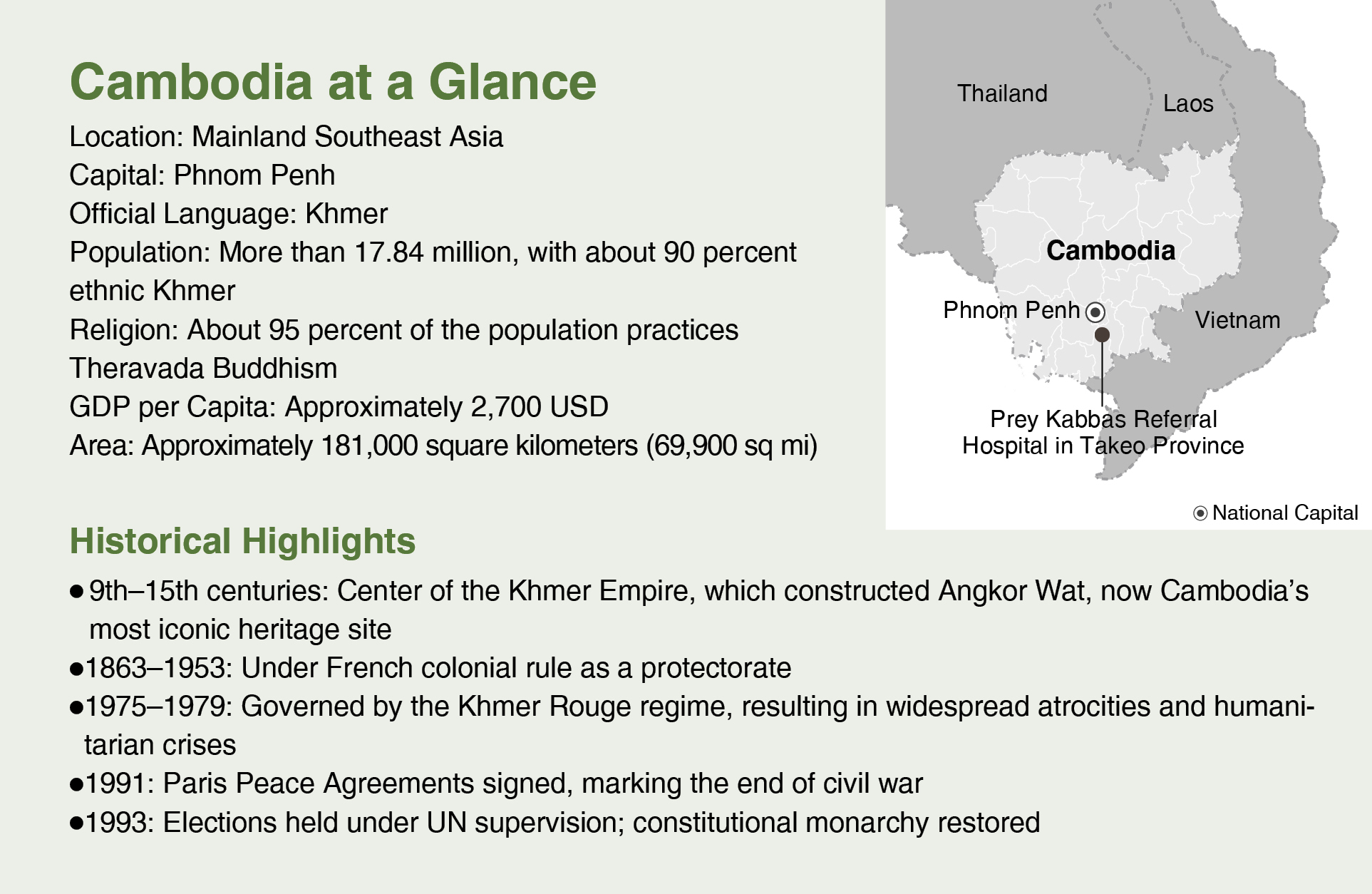

In late spring, I traveled with a Tzu Chi team from Taiwan to Cambodia to report on a free clinic for Tzu Chi Monthly. Our 90-minute drive south from Phnom Penh International Airport to Takeo Province offered a vivid glimpse of Cambodia’s blend of old and new. Tuk-tuks, motor scooters, and Japanese-imported cars shared the roads, while the route was lined with garment and shoe factories, snack stalls and carts, traditional stilt houses, and Buddhist temples. This mix of modern and traditional scenes reflected the country’s closely intertwined urban and rural life.

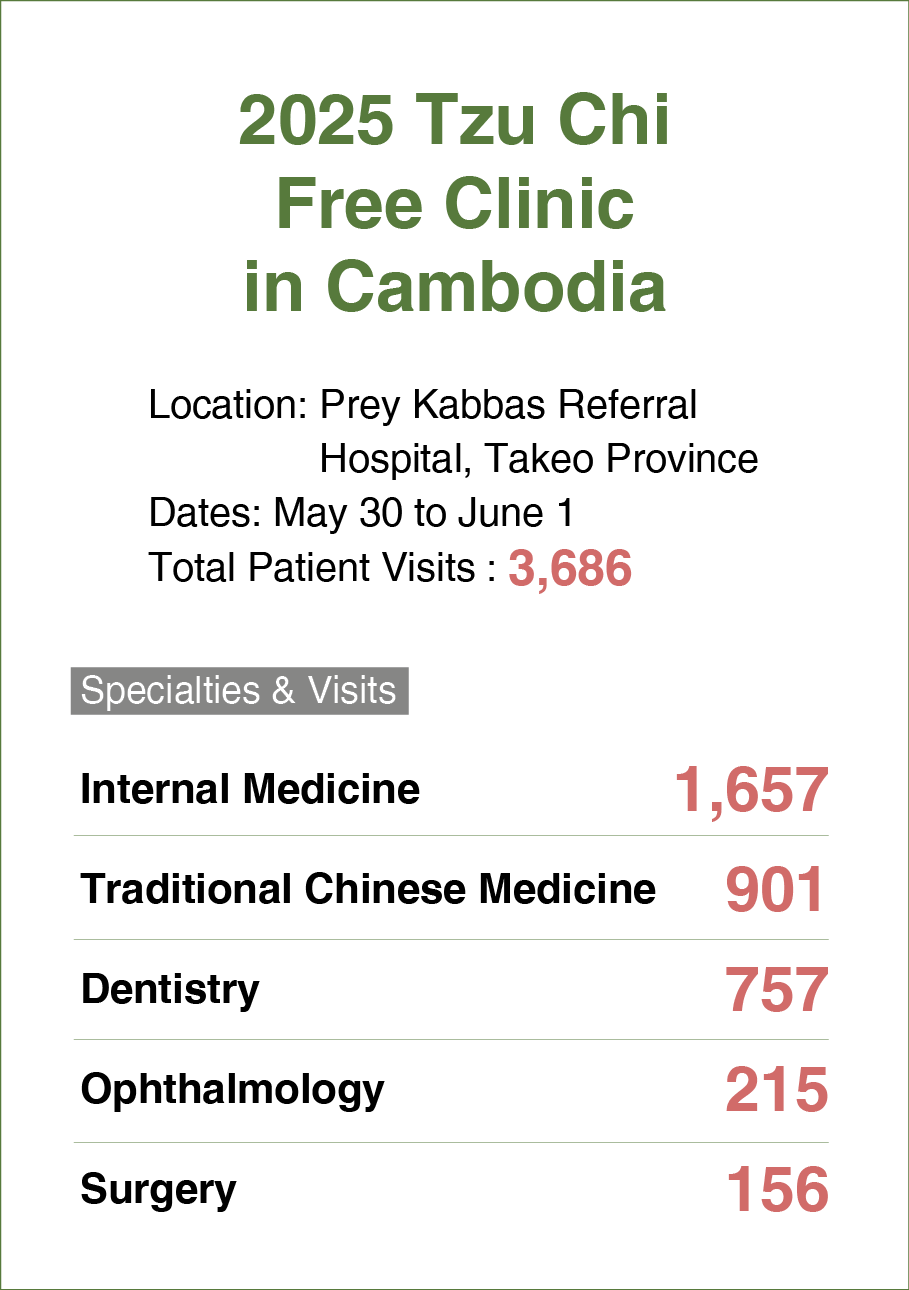

Our destination was Prey Kabbas Referral Hospital, where Tzu Chi held a large-scale free clinic in partnership with the Samdech Techo Voluntary Youth Doctor Association (TYDA). This event, one of the free clinics regularly conducted by the two organizations, offered services in five specialties: ophthalmology, dentistry, surgery, internal medicine, and traditional Chinese medicine. Over three days, from May 30 to June 1, the clinic recorded nearly 3,700 patient visits.

The clinic began at 10 a.m. on the first day. By the time the Taiwan team and I arrived around noon, a sizable crowd had gathered outside the hospital, waiting to register. Tzu Chi volunteers and local youth helped patients fill out basic information forms and sign up for the appropriate departments based on their medical needs. Though the young volunteers still carried a sense of innocence, their focus and sense of responsibility stood out.

Tzu Chi’s Singapore team had visited the site a month prior to the clinic to conduct a field survey. Then, two days before the event, they joined Cambodian volunteers to begin setting up the venue in preparation for the arrival of teams from Malaysia, the Philippines, and Taiwan.

The surgery and ophthalmology departments were located in the same building. It was there that I saw Chhom Sophea undergoing surgery. His broad frame made the operating table seem small. Dr. Chien Sou-hsin (簡守信), superintendent of Taichung Tzu Chi Hospital in central Taiwan, performed the procedure, removing tumors from his back and arm.

After the operation, I found Chhom waiting to receive medication and attend a health education session. I was able to interview him with the help of a college student volunteering on-site, who translated Chhom’s Khmer into English. He told me he had been living with the tumors for six years, and that whenever he lay down, the pressure on them caused him discomfort.

Although speaking to a reporter, Chhom answered my questions without hesitation, his eyes gentle and at ease. In fact, I encountered this same openness and calm sincerity throughout the rest of my interviews with local residents, who all shared their experiences freely.

Dr. Chien later explained that in Taiwan, doctors would typically monitor benign tumors like Chhom’s through follow-up visits, and only proceed with surgery if needed. “But since this is a free clinic in Cambodia,” he said, “monitoring a tumor is often difficult for patients. Thus, we opt to remove them immediately, giving them peace of mind.”

The surgery removed not only the tumors, but also a burden of anxiety that had weighed on the patient’s heart for years.

Orthopedic doctor Hung Shuo-suei (洪碩穗, middle) and Taipei Tzu Chi Hospital Deputy Superintendent Chang Heng-chia (張恒嘉, second from left) conduct a joint consultation at the internal medicine department during the free clinic. Cross-department collaboration boosts the clinic’s effectiveness.

Caring for vision

When I visited the ophthalmology department on the second day of the free clinic, the waiting area was full of patients. Most had undergone preoperative screenings earlier that month, on May 3 or 4. Each patient wore a label affixed to their forehead above the affected eye, marked with either a “C” for cataract or a “P” for pterygium. For those scheduled for cataract surgery, the label also displayed a number that matched the serial code on their intraocular lens box, helping to ensure the correct lens was used during the procedure.

Nearby, over a dozen patients were having their pupils dilated with eye drops, which would take at least 15 minutes to take effect.

One woman stood out to me: Kart Eng, dressed in a blue shirt, her eyes tinged with sorrow. Through an interpreter, I learned she was 69 years old and had experienced blurred vision for some time. About two months before the clinic, she also began noticing a dark shadow in her right eye.

She soon changed into a surgical gown and cap and waited quietly for her turn. Before the operation, her surgeon administered local anesthesia. Then, under a surgical microscope, the surgeon used an ultrasonic probe to break up and suction out her clouded natural lens. Each cataract surgery typically took between ten and 30 minutes to complete.

Dr. Antonio Say (史美勝), who led the ophthalmology team from the Philippines, pointed out that all the surgeons on this mission were highly experienced. They worked with care and precision, and were determined to ensure that every registered patient received the treatment they needed. Four operating tables were in constant use, with patients rotating in and out in a steady rhythm. Rapid sterilization equipment allowed for quick turnover between procedures. In this manner, the ophthalmology team completed 108 surgeries for cataract and pterygium in just two days.

After her surgery, Kart slowly sat up, her expression dazed, as though she hadn’t quite regained her bearings. As soon as she saw us, she brought her palms together in a gesture of gratitude. Her well-meaning gesture, bringing her hands close to her face so soon after eye surgery, carried a risk of infection. The surgeon, clearly concerned, quickly cautioned us to ensure she didn’t touch the surgical site.

Postoperative patients were then guided to a recovery area, where they rested briefly, received anti-inflammatory eye drops, and listened to instructions for post-surgical care. Kart said her vision was still a bit blurry and that she felt a mild stinging sensation in her eye.

The average monthly income is relatively low in Cambodia. A single cataract operation can cost between 200 and 500 U.S. dollars, depending on the type of intraocular lens and surgical method used. When factoring in travel, hospital stays, and medication, the overall expense can be a heavy burden—especially for retirees like Kart Eng. Thus, free eye surgery represents a significant opportunity for many people in the country.

Patients in surgical gowns and caps (photo 1), with labels affixed to their foreheads, wait for cataract surgery. A volunteer applies dilating eye drops to a patient before the procedure (photo 2). Dr. Antonio Say (second from right in photo 3) from the Philippines examines a patient’s recovery the day after her surgery. Photos 1 and 3 by Jamaica Mae Digo; photo 2 by Chai Mong Ping

Free yet effective care

Mao Sareorn, 60, was among the patients in the dental department. For nearly a year, she had endured a persistent toothache that severely impacted her daily life. The pain would, at times, trigger intense headaches that left her unable to work. She weaves fabric at home, earning about a hundred U.S. dollars for each bundle, which takes her two months to complete. With such modest earnings, the dental pain that from time to time forced her to stop working only added to her financial strain.

It wasn’t that she had never sought treatment for tooth pain. Five years earlier, she had visited a private clinic for a tooth extraction, which cost ten U.S. dollars. Though that might not seem expensive to some, it was enough to deter her from seeking dental care when she experienced the same problem again. According to dental students volunteering at the free clinic, current fees at private clinics can range from 20 to 50 dollars for tooth extractions—a financial stretch for many patients.

After her tooth was removed at the free clinic, Mao bit down on a cotton ball to stop the bleeding and then headed to the internal medicine department to address digestive issues. Because of the cotton still in her mouth, she could only nod or shake her head in response to the doctor’s questions. I wasn’t able to interview her, but I silently hoped she felt some relief, now that the source of her pain had finally been taken away.

Nearby, Yin Sarim had just received her first-ever teeth cleaning. She proudly showed us her bright white teeth before making her way to internal medicine. Like Mao Sareorn, she earned a living through weaving, often working long hours at her loom. Recent financial pressure at home had left her feeling anxious, pushing her to work even harder. Perhaps because of this stress, she had begun experiencing gastrointestinal discomfort. The doctor advised her to eat meals at regular times—simple advice, but often hard to follow for someone preoccupied with making ends meet.

Dr. Ho Ching-liang (何景良) from Taipei Tzu Chi Hospital, who treated Yin Sarim, observed that many patients at the clinic suffered from digestive issues. Given the limited diagnostic tools on-site, he relied heavily on clinical judgment and patient interviews to prescribe appropriate medications and offer guidance on symptom management—doing what he could within the constraints of the setting.

Hsieh Ming-hsuan (謝明勳), head of Tzu Chi Cambodia, explained that while public clinics offer subsidized consultations to those with work permits, assistance usually ends there. Patients are often required to cover the cost of medication themselves, which can be a significant financial burden for those with limited means.

One dentist performs the treatment as others assist with suction, lighting, and other supportive tasks. Chai Mong Ping

The meaning behind the numbers

On the third morning of the free clinic, as the medical team arrived, patients waiting in the ophthalmology area stood and applauded—they could already see more clearly.

We happened to run into Kart Eng during her follow-up visit. She was wearing the sunglasses the doctor had given her after surgery to protect her healing eye. She told us that the vision in her right eye had noticeably improved and that her recovery had gone smoothly, with minimal discomfort. She was very happy.

Her husband, nearly 80, had come with her and was preparing to undergo cataract surgery himself. He didn’t appear nervous, perhaps reassured by how well his wife had fared. We took a photo of the couple—both smiling brightly, a moment full of warmth and joy.

Looking back on the three-day event, surgical care often provided the most immediate relief, whether patients were dealing with recent problems or conditions they had endured for years. The internal medicine and traditional Chinese medicine departments focused on diagnosis and patient education. While doctors prescribed medications when needed, they also emphasized guidance on healthier daily habits. In the dental department, services such as extractions, cleanings, and fillings helped patients maintain quality of life and prevent further pain.

No matter the department, doctors went the extra mile for their patients, hoping to offer just a little more care and make just a little more difference.

Behind the nearly 3,700 patient visits logged over the three days were thousands of brief yet meaningful encounters between doctors and patients. Though fleeting, many of these moments are sure to leave a lasting impression—on both sides.

Behind the Scenes of the Free Clinic

A month before the event, Tzu Chi’s Cambodian volunteers and doctors from TYDA began conducting preoperative eye screenings to prepare for cataract and other surgeries that would be performed by physicians from the Tzu Chi Eye Center in the Philippines. The ophthalmology team from the Philippines brought 22 boxes of instruments, medications, and medical supplies (photo 1) and conducted multiple equipment tests and trial runs (photo 2).

Meanwhile, Tzu Chi’s advance team from Singapore arrived with 31 boxes of equipment and essential items. They set up the site at Prey Kabbas Referral Hospital in Takeo Province, organizing areas for consultation, treatment, and pharmacy services (photos 3 and 4).

Photos 1 and 2 by Jamaica Mae Digo; photos 3 and 4 by Yang Zhi Huang