By Shi De Zao

Abridged and translated by Rose Ting

Photos by Huang Xiao-zhe

Be grateful for this piece of paper. Be grateful for this drop of water. Because of your gratitude for them, you’ll love them, cherish them, and do your best to conserve them.

—Dharma Master Cheng Yen

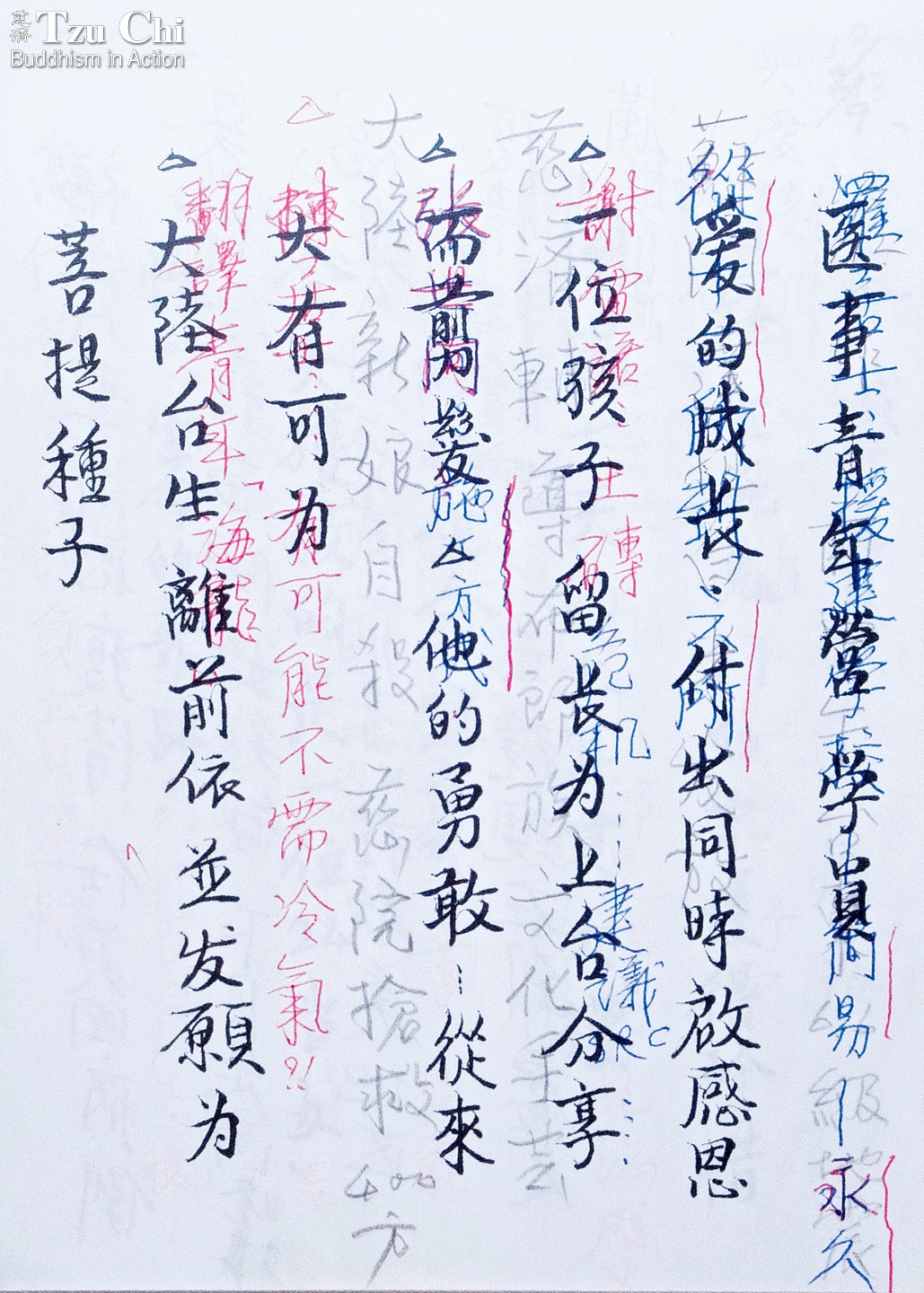

A sheet of paper shows some outlines for Master Cheng Yen’s talks. To maximize the use of the paper, the Master first wrote on it with a pencil, then a blue-ink pen, then a red-ink pen, and then a writing brush. COURTESY OF THE JING SI ABODE

A habit of frugality and conservation is woven into the fabric of daily life at the Jing Si Abode. It’s been there since its establishment.

Resources were extremely scarce when the Abode was first established by Dharma Master Cheng Yen in Hualien, eastern Taiwan, more than half a century ago. The Master and her monastic disciples supported themselves through their own efforts, holding firm to a decision not to accept offerings from others. They sewed baby shoes, converted concrete sacks into smaller animal feed bags, grew their own vegetables, and did other work to provide for their basic necessities. Even so, they earned barely enough to support themselves. Amidst this difficult life, Master Cheng Yen taught everyone at the Abode to cherish and conserve everything they had. By doing so, they were able to prolong the life of things, reduce expenses at the Abode, and even cut down on the amount of garbage they produced. A lifestyle of frugality and conservation was thus established at the Abode.

The Master is the living embodiment of her own teachings. The necessity to lead a frugal life aside, she holds a deep-seated appreciation for everything that passes through her hands. For example, most people use a piece of paper once before throwing it away, but not her. “I just can’t bring myself to toss a piece of paper after just one use,” she says. Instead, she extends its life and usefulness by writing on it first with a pencil, then a blue-ink pen, then a red-ink pen, and then a writing brush.

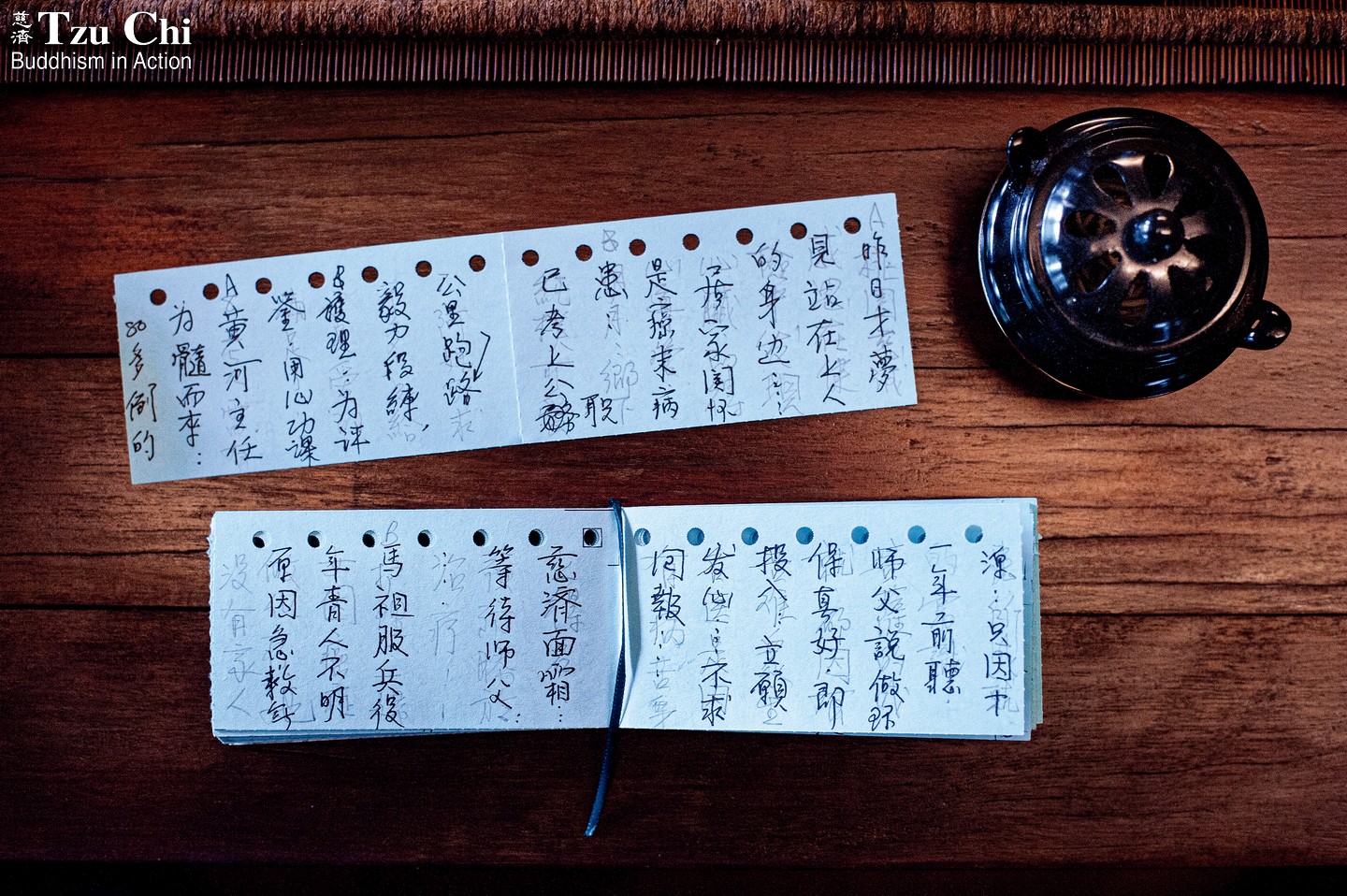

Another example of her conservation habits is the memo notepads she uses, which are made of the unused paper in the margins of donation receipts. She doesn’t want the unused margins of the receipts to go to waste, so she has the extra paper from the margins made into notepads to use. She even writes repeatedly on these small pieces of paper to make thorough use of them.

The same attitude goes toward the use of water. Master Cheng Yen knows that water is a very precious resource and must be used with care. She makes sure that not a drop goes to waste. She saves the washbasin of water she uses to wash her face in the morning to wash her hands throughout the day. Her shower water is collected and used to flush the toilet.

The Master can’t even bear to see rainwater going to waste. “We must treasure and cherish all resources in the world,” she said. Rainwater is captured and stored in a reservoir built in the basement of the Tzu Cheng Building at the Abode. It’s then used to irrigate plants and clean toilets and bathrooms.

The Master saves electricity by using as little as possible. Her study is usually dark. If she does need light to read, she turns on just her desk lamp. She’s maintained this practice day in and day out for over half a century.

“Turn off lights when they are not in use” is something she often reminds everyone to do, just as she urges everyone not to leave tap water running. Even though these things are lifeless, “it’s like we’re killing their lives if we let them go to waste,” she remarked.

Master Cheng Yen also takes issue with those who replace their cell phones or other items they own too often. She encourages people to harbor gratitude for everything they own. That way, they will cherish and treasure everything that passes through their hands. They will be content with what they have and make it last as long as possible.

“Be grateful for this piece of paper. Be grateful for this drop of water,” she said. “Because of your gratitude for them, you’ll love them, cherish them, and do your best to conserve them.”

Memo notepads made of unused paper from the margins of donation receipts. Master Cheng Yen writes on them repeatedly to conserve the paper.

Waste not, want not

Following the Master’s teachings and example, the nuns at the Abode cherish water as if it was gold. When they do laundry, they wring the clothes as dry as they can and save every drop of water for later use. They also collect the water with which they wash their hands and use it to flush the toilets. Water that is used to wash vegetables before cooking is saved to clean tools, mop the floor, or water plants and vegetables. The water used to wash rice prior to cooking is kept aside for irrigation, or to wash pots and pans.

Some of the monastics at the Abode aren’t eloquent in encouraging people to practice conservation, but they promote a life of gratitude and frugality just the same by silently practicing the Master’s teachings in every possible way. They turn off lights after use, and keep an eye out for those that have been accidentally left on by others. “This is my home,” they say. “It’s a matter of course I’ll do things that are good for it.”

Master De Quan (德佺) oversees general affairs at the Abode. A devout believer of everything Master Cheng Yen teaches, she adheres to the principle of “Never buy a new item if the old one is still usable.” A usable item at the Abode often goes through repair after repair until it is completely worn out. Even when it can no longer be fixed, its parts are sometimes salvaged and adapted for other uses.

For example, Master De Quan will take apart a broken electric fan and convert the blade guard into a drying rack for sun- or air-drying laundry. A recycled metal rack can be fitted with elastic bands and become a holder for laundry basins. Bottle pumps are great for dispensing just the right amount of product without the unwanted mess, but when the product in the bottles, such as shampoo, is used up, the dispensers are often thrown away along with the bottles. Not so for Master De Quan. She converts the pump dispensers for use in larger bottles of cleaning agents.

Some time ago, all the pillows in a dormitory for male volunteers at the Abode were replaced with new ones. Making use of her spare time, Master De Quan spent seven days sewing those old pillows into a large mattress. She makes sure that nothing goes to waste.

Examples like this abound. Master De Quan constantly taps into her resourcefulness to extend the usefulness of an item. Her ingenuity not only cuts down on expenses at the Abode but, more importantly, prolongs and reinvents the life of things.

Leading the way

One of the ways the monastics at the Abode support themselves is by making instant rice and multigrain powder for sale. What becomes of the rice sacks and large plastic bags the ingredients come in?

Besides reusing the plastic bags, nuns at the Abode make the rice sacks into all sorts of carrying bags. Aphorisms by Master Cheng Yen are inscribed on the bags to add to their appeal. Learning from the nuns, Tzu Chi volunteers in Africa fashion used rice sacks into carrying bags too. The sacks originally contained rice donated by the Taiwanese government for distribution to needy people in other countries.

The aprons the monastics at the Abode wear when they wash vegetables or do the dishes are made from recycled plastic bags too. Many volunteers have lauded the nuns’ inventiveness. “This is really creative. I’ll copy it,” some said.

“A plastic apron sells for ten Taiwanese dollars [35 U.S. cents] on the market,” a nun commented. “But if we make one from a recycled bag, it costs nothing at all.”

Every day at the Abode, enough food needs to be cooked to feed hundreds of people. The packaging and plastic bags the food and ingredients come in are also carefully recycled—after they have been washed and sun-dried.

Master De Huan (德渙) used to be the one cleaning and sorting these bags for recycling. “Master Cheng Yen urges everyone to clean their recyclables before disposing of them,” said Master De Huan. “We at the Abode have the responsibility to set a good example and lead the way.” She did the recycling work outside of her formal duties. She tried to make as much time as possible for it, knowing that the more effort she put in, the cleaner the Earth would be.

Sometimes she’d work as late as eight or nine in the evening. At first she doubted that she’d be able to keep it up, but she persisted. “Since I’ve chosen to follow the Master, I must do what she wants us to do.”

Because some bags are soiled or greasy, preparing them for recycling takes a lot of time. Master De Huan volunteered for the work three years running, after which Master De Xi (德皙) took over. It has since been her formal duty. Like her predecessor, she embraces a sense of mission for her work, knowing that what she does is good for the health of Mother Earth. “I never think much about what I do. When it comes to the right thing, we should just do it,” she said, summing up her mindset.

Volunteers from Yilan, northern Taiwan, are responsible for collecting the bags at the Abode and transporting them for recycling. They say that the bags processed at the Abode are so clean and well-sorted that they can be sent directly to factories to be melted into polyester pellets for further processing.

Large plastic bags are recycled into aprons for people to wear at the Abode when they do the dishes or wash vegetables.

Zero kitchen waste

The Jing Si Abode is like a big family, where steady food supplies are important. Dried vegetables such as cabbages and cauliflowers are among those regularly stocked up for later use. The bags used to store the dried vegetables are also recycled.

Due to COVID-19, a lot of farm produce could not be exported from Taiwan in February and March of 2020. In response, the Abode purchased truckload after truckload of cauliflower, cabbage, and yam bean from farmers to help them out. The vegetables were then processed and dried for storage. Even after enough had been purchased to fully stock the Abode, the Master asked her disciples there to keep purchasing from farmers. In addition to saving for a rainy day, the Master didn’t want farmers’ labor of love to go to waste. The extra food they bought beyond their own needs could always be donated to people in need.

Vegetables are dried with fire at the Abode. An old-style smokeless drying machine that uses wood as fuel serves this purpose. The wood used to feed the machine is recycled from discarded shipping pallets. Volunteers transport the pallets to the Abode, then cut them into uniform pieces to make it easier to feed them to the drying machine.

It has long been a tradition at the Abode to dry and preserve food for later use. During the early days when the Abode was first founded, the nuns often didn’t know where their next meal would come from. It’s no wonder food was deeply cherished, and no parts of a vegetable were wasted. Take daikon radishes, for example. Even the skins and stalks were cooked as food or preserved for later use. Master De Ru (德如) said that necessity helped the nuns develop a habit of frugality. The tradition of wasting no part of a food has endured at the Abode ever since.

In many households, things such as soybean dregs or fruit peels end up in the garbage can. But not so at the Abode: the kitchens here produce zero waste. Soybean dregs are made into food such as vegetarian meat floss. Inedible food scraps are recycled into compost to nourish soil and grow more crops. Fruit peels are used in making soap or as a source of eco-enzymes for cleaning purposes. Even pruned tree branches and leaves do not go to waste. They are shredded and made into compost.

A nun at the Abode shells Inca nuts grown on site, using only a single desk lamp in the dark room to save on electricity. The monastics at the Abode lead a lifestyle of frugality and conservation.

Blade guards from broken fans are converted into drying racks for air-drying laundry.

Master De Ding (德定) has lived and carried out spiritual practice at the Abode for 33 years. She’s been in charge of the recycling work there for the past 20 years and handles recyclable items day in and day out. She says that many people know recycling is important and necessary, but not many people faithfully carry it out in their daily life. That’s why she especially admires the Tzu Chi recycling volunteers working in various communities. “They willingly pitch in to collect and reclaim reusable resources no matter what their economic standing or social status is. They don’t mind the bad smells from the trash or whether their hands get dirty. They didn’t even shy from the work when the threat of COVID-19 was at its most severe.”

From the Abode to communities in Taiwan and abroad, members of the Tzu Chi family follow Master Cheng Yen’s teachings and personal example and do what they can to help the Earth. Though a single individual may not be able to accomplish much, when the work and effort of many individuals are combined, a big difference is possible.