By Ronaldo, Nuraina, Yanti Yunita, Hidayat Sikumbang, Pipi Susanti, and Ari Zoelva

Translated by Wu Hsiao-ting

After Cyclone Senyar, severed roads and power outages made Tzu Chi’s relief work extremely difficult. Volunteers used every available means of transportation to reach isolated communities with life-saving supplies.

Volunteers wade through floodwaters to deliver food and drinking water to affected residents sheltering at a mosque in Deli Serdang, North Sumatra, on November 30. Kamin

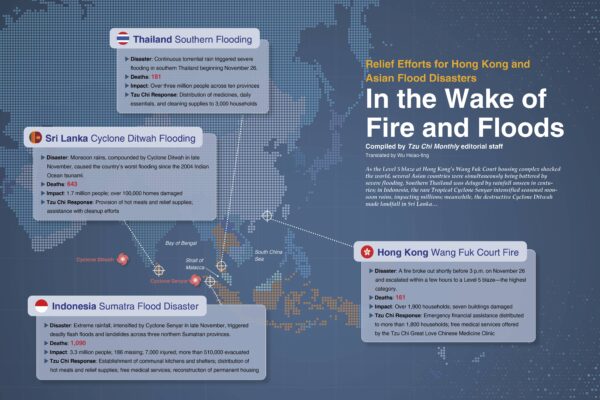

Tropical cyclones rarely form in the Strait of Malacca near the equator, yet Cyclone Senyar broke that pattern, becoming the first to do so in 140 years. Making landfall in Indonesia on November 26, 2025, it intensified the extreme rainfall that had been pounding northern Sumatra for days. Rivers overflowed, flash floods swept through communities, and key transportation routes were cut off.

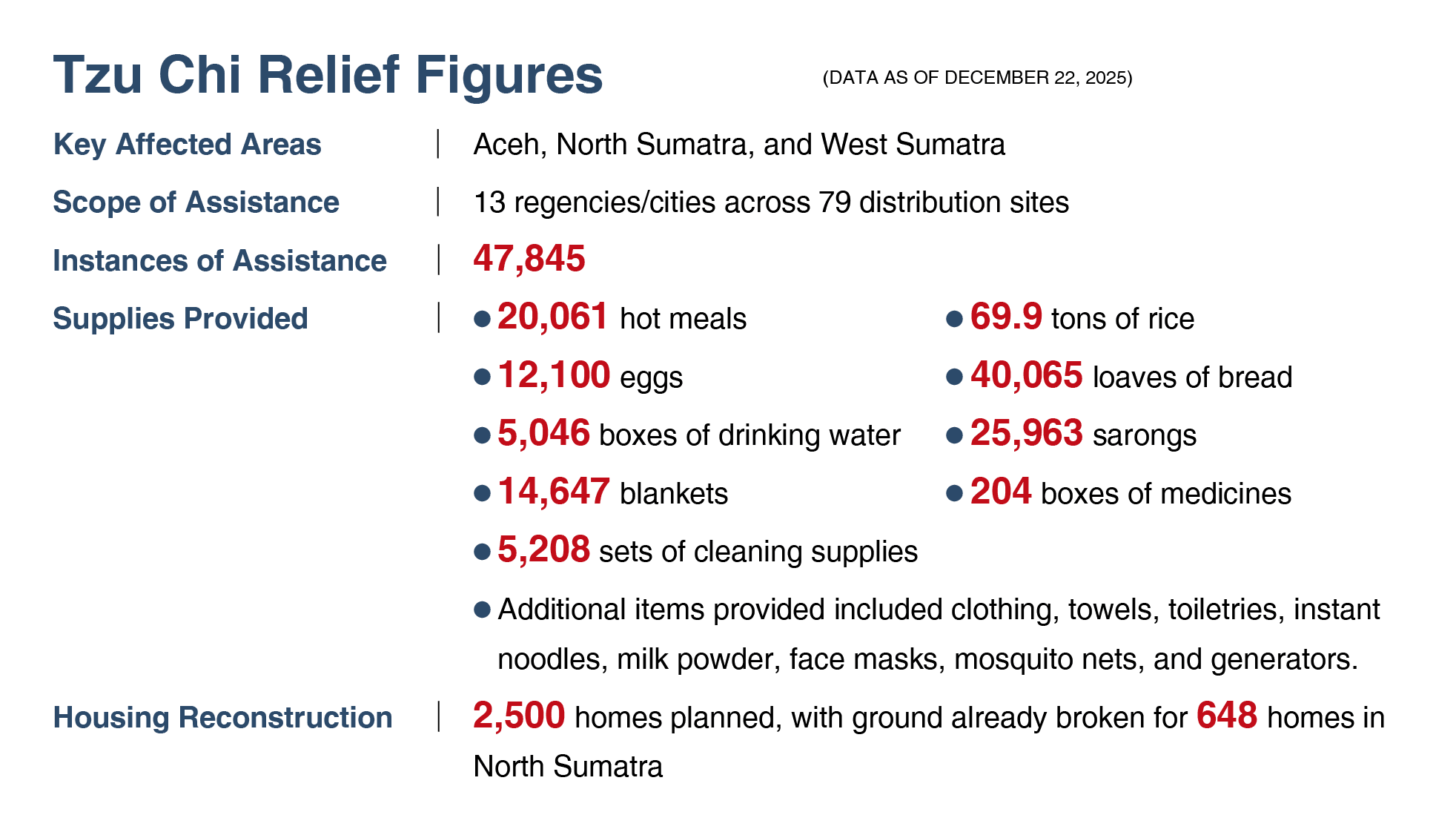

The storm battered the three Sumatran provinces of Aceh, North Sumatra, and West Sumatra. According to early December figures from Indonesia’s National Agency for Disaster Management, more than 1,200 people were killed or went missing, nearly 510,000 were evacuated, and 3.3 million were affected. These are not just statistics—they represent millions of real people whose lives were suddenly upended.

Deforestation has undermined Sumatra’s soil stability and water retention. Torrential rains from Cyclone Senyar triggered mudflows, leaving areas around Medan blanketed in mud and debris, as shown in photo 1. Navigating damaged mountain roads, volunteers from Padang deliver relief supplies to Agam Regency and other areas (photo 2). Photo 1: Leo Rianto; Photo 2: Pipi Susanti

Meals prepared despite blackouts

Medan, the largest city in North Sumatra, is usually a bustling commercial hub, but the relentless rain transformed it into a waterlogged landscape. Murky yellow water inundated streets, shops, and homes so quickly that many residents had no time to pack their belongings before fleeing to temporary shelters. Despite the danger, however, some chose to stay behind to look after their homes.

Power outages plunged daily life into further chaos. Amid the confusion, a faint light shone from the home of Tzu Chi volunteer Sani Husiana (郭春霞). On the morning of November 28, after a disaster response meeting, her home was quickly converted into a temporary communal kitchen. “It was extremely urgent,” she recalled, still sounding tense. “All the volunteers sprang into action, buying ingredients and starting to cook.”

Tzu Chi eventually set up more than 30 such communal kitchens, producing thousands of boxed meals under very basic conditions. Volunteers then waded through waist-deep muddy water to deliver hot meals, uncooked rice, and bottled water. In Baru Village, 64-year-old Nuraini huddled with her grandson in the corner of a mosque. They had not had a proper meal in three days, surviving only on a little bread salvaged by neighbors. When volunteers handed her some warm food, the resilient grandmother’s voice trembled as she said, “Thank you so much. There’s no water, no electricity—the wiring has short-circuited. Everything is ruined. We just can’t go home.”

In addition to food and water, volunteers delivered clothing, sarongs, cleaning supplies, and other necessities to Medan and surrounding areas. In Klumpang Kebun, Deli Serdang, residents stood in floodwaters and formed a human chain to move the supplies that had been brought to their community. A young mother’s eyes welled with tears as she received warm meals, explaining that her family had gone two days without eating. “Praise be to Allah,” she exclaimed. “Finally, someone has come to help us!”

As the rain subsided and floodwaters gradually receded, sanitation conditions deteriorated rapidly. Skin infections, diarrhea, and colds began spreading in shelters. Tzu Chi quickly launched medical relief efforts, though access to some areas remained difficult. In South Tapanuli, mountain roads leading to Batang Toru were blocked in several places by landslides and had to be cleared by heavy machinery. Volunteers, working alongside the military and police, navigated muddy, treacherous roads for over four and a half hours to deliver medicines and daily necessities.

One shelter in Batang Toru housed about 600 residents from three villages. A notice posted on a bulletin board reported that 56 homes had been completely destroyed, with some residents still unaccounted for.

Hari Kesumua, a physician with the Tzu Chi International Medical Association, examined residents and prescribed medication for diarrhea, itchy skin, and other conditions. “They’ve lost their homes and urgently need food and medicine,” he said. “The disaster is severe, and we’re grateful to be able to ease some of their burden.”

Physicians from the Tzu Chi International Medical Association provide free medical care to people affected by the floods. Skin infections, colds, and other infectious diseases were common in the wake of the floods. Liani

A volunteer respectfully hands a bag of supplies to a flood survivor. Courtesy of Tzu Chi Indonesia

Delivery via zipline and boats

As people struggled to cope, a harsh reality became impossible to ignore: In just two or three days, Cyclone Senyar dumped hundreds of millimeters of rain, far exceeding the region’s average monthly rainfall. Years of unchecked land development had further heightened the risks of flooding and landslides.

Indonesia’s largest environmental movement organization, the Indonesian Forum for the Environment (WALHI), reported that between 2016 and 2025, roughly 1.4 million hectares of forest in northern Sumatra were cleared for plantations and mining. With this natural sponge stripped away, rainwater can hardly be absorbed by the soil. Instead, it surges over exposed land, triggering highly destructive mudslides. This explains why, during extreme rainfall, villages can be swiftly engulfed by mud, while roads and communication infrastructure suffer severe damage.

The disaster cut off transportation links in multiple communities in the regencies of North Tapanuli and Central Tapanuli, as well as in the city of Sibolga, all in North Sumatra, isolating communities like islands. With ground access impossible, Tzu Chi partnered with the military to deliver relief by air. Helicopters airdropped supplies, including 4,000 towels, clothing, plastic mats, and hundreds of boxes of instant noodles and bottled water. Such efforts provided a vital lifeline to stranded residents.

In Kutablang, Bireuen Regency, Aceh Province, a bridge was washed out by a raging stream. Residents on the opposite bank, cut off from the outside world, had exhausted their remaining food supplies. After volunteers reached the site, they worked with rescue personnel to set up an aerial zipline. Box after box glided across the gap, delivering food and daily necessities into the outstretched hands of those anxiously waiting on the other side.

Conditions were also dire in Kuala Simpang, Aceh Tamiang Regency. Completely cut off from food and clean water, residents sent desperate pleas for help through social media. Volunteers from Medan did everything they could to reach them. When the land route proved impassable, they turned to the waterways. On December 3, a team led by volunteer Shu Tjeng (楊樹清) traveled by vehicle from Medan to the Port of Pangkalan Susu, transferred to a large boat, and then boarded small wooden vessels capable of navigating shallow waters. After days of isolation, the residents finally received much-needed supplies.

Hundreds of thousands of people elsewhere in Aceh sought refuge in evacuation centers. Clean drinking water and food were in short supply. Pidie Jaya Regency, about 220 kilometers (135 miles) from Banda Aceh, suffered devastating losses when floodwaters thick with mud and massive logs slammed into homes, killing 20 people. In the village of Cot Gadong, one of Tzu Chi’s distribution sites, evacuees packed into a mosque. When night came and the cold set in, they wrapped themselves in the blankets and clothing delivered by volunteers to keep warm.

Volunteers distribute food and bottled water to flood victims. Liani

Mutual help

In the wake of the floods, alongside other relief work, Tzu Chi volunteers helped set up shelters and install water towers to supply clean drinking water. But about two weeks later, in mid-December, the devastation remained stark. In Karang Baru, Aceh Tamiang Regency, floodwaters had left almost surreal scenes: cars swept up and lodged against walls and streets buried under tens of centimeters of mud. The roar of heavy machinery echoed constantly as debris was cleared. With no clean water for washing, many shelter residents still bore mud stains on their bodies.

But the situation wasn’t all bleak. Amid the destruction, a sense of order and mutual support emerged. Many people were themselves flood survivors, but once they ensured their own families were safe, they chose to help neighbors in even greater need.

Palembayan, Agam Regency, West Sumatra, provides a clear example. Tzu Chi volunteers from Padang, the capital of the province, endured a grueling road journey, arriving at 4:30 a.m. on December 4 to deliver badly needed supplies.

Local residents had already organized a communal kitchen, and each household had contributed about 7,000 Indonesian rupiah (US$0.45) to compensate those who cleared debris and reopened roads each day. In addition to delivering food, baby diapers, fuel, and clothing, Tzu Chi provided a generator to power the communal kitchen until electricity could be restored.

With transportation in many stricken areas still disrupted and streets littered with mud and debris, much work remains to be done. Once the emergency relief phase concludes, Tzu Chi will assist with bridge repairs to support recovery and work with the government to build safe, permanent housing for affected communities. The road ahead is long, and although some communities were once isolated like islands, they are not alone. Tzu Chi will continue to accompany survivors as they rebuild their homes and their lives.