Narrated by Joyce Chen, executive director of the Taiwan Vegetarian Nutrition Society

Compiled by Yeh Tzu-hao

Edited and translated by Wu Hsiao-ting

Photo courtesy of Joyce Chen

Joyce Chen, executive director of the Taiwan Vegetarian Nutrition Society

- Plant-based diets are both low-carbon and healthy, helping to reduce the risk of chronic diseases.

- Eating vegetarian doesn’t mean you’ll get hungry sooner; the key is having the right proportions.

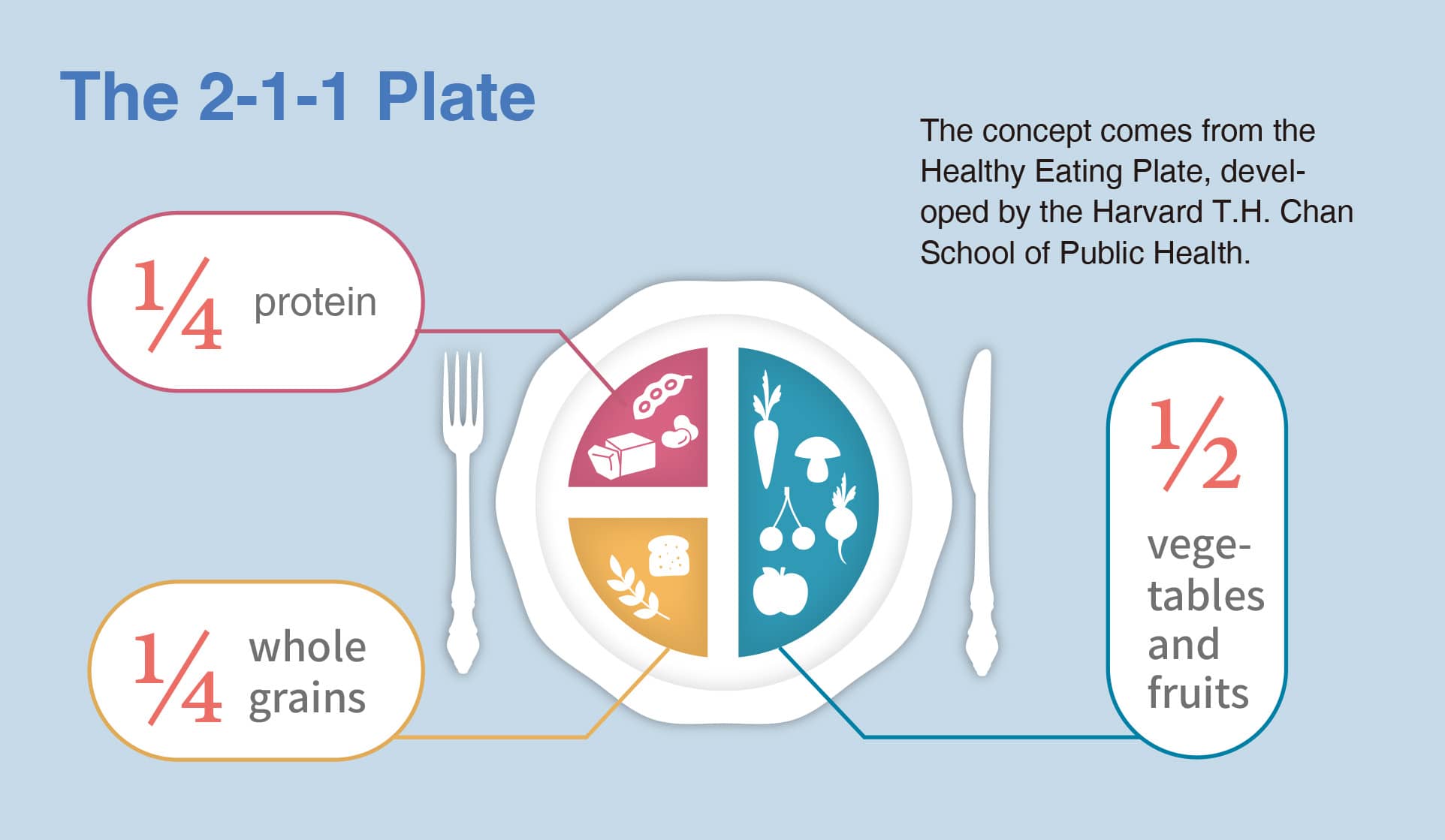

- The 2-1-1 Plate is easy to remember: half vegetables and fruits, and the other half divided evenly between protein and starches.

- Nutritional needs vary by age group.

Around the world, sustainability, ESG (environmental, social, and governance) initiatives, and the UN Sustainable Development Goals are gaining momentum. As part of this movement, many countries are seeking to cut carbon emissions through dietary changes. In Taiwan, eating out or ordering food from restaurants is very common, and per-capita meat consumption has reached 87 kilograms (190 pounds) per year, contributing to a high dietary carbon footprint. This is why many civic groups are actively promoting vegetarian or plant-based eating as a way to reduce emissions.

Plant-based diets tend to be nutrient-dense, lower in calories, and faster to digest, meaning the food doesn’t linger in your system for long, which can actually be beneficial. But does this mean that vegetarians get hungry more easily? That might happen, but the key to avoiding it is adopting the right eating habits.

A common issue among vegetarians is not eating enough vegetables or fruits, and not getting sufficient protein. Instead, many consume too many refined carbohydrates, such as white rice or noodles. Take a typical store-bought Taiwanese lunchbox, for example: Even though it may come with three side dishes (usually vegetable-based), the portions of the side dishes are usually smaller than the serving of rice. In addition, many vegetarians don’t eat enough beans or bean products, which can leave them feeling hungry sooner.

The 2-1-1 Plate is a simple idea for anyone who wants to eat plant-based and stay healthy. Divide your plate into two halves. One half should be vegetables and fruits, with vegetables as the main portion. Because vegetarians are more prone to iron and calcium deficiencies, it helps to emphasize dark green vegetables, such as kale, collard greens, Chinese kale, or red amaranth. Bok choy, though not dark green, is also relatively high in calcium. Vegetables like bell peppers, tomatoes, and eggplants can be added for color and variety.

The other half of the plate should be split evenly between protein and staple foods. The best protein sources are whole legumes, such as lentils, chickpeas, or beans. For the quarter of the plate allocated to staple foods, choose whole grains like brown rice to stay full longer. Starchy root vegetables—such as sweet potatoes or pumpkins—can also be included.

Children, who are more active, can have some refined starches for quick energy. Mixing half brown rice with half white rice is a good way to help them get used to the texture of whole grains from an early age.

For older adults, preventing muscle loss is especially important, making adequate protein intake crucial. Many seniors have smaller appetites and struggle to eat enough protein, which can lead to rapid muscle decline. As a general guideline, daily protein needs in grams are roughly equal to one’s body weight multiplied by 1.2. (For example, a 60-kilogram person should take in 72 grams of protein each day.) Plant-based protein powders, prepared as a drink, can be a convenient supplement—they are concentrated, low in volume, and easy to consume, helping seniors meet their daily protein requirements.

Bone health is another major concern for seniors. Bone density peaks around age 30 and declines thereafter. Post-menopausal women experience even faster bone loss than men, so their diets should particularly emphasize protein, calcium, vitamin D, and vitamin B12. Even so, diet alone isn’t enough to maintain muscle or bone density—exercise is essential. Some seniors do moderate weight-bearing workouts at the gym, which is an excellent way to support muscle strength and bone health.

Research consistently shows that people who consume more meat tend to have higher rates of obesity and chronic disease. Red meat, for example, is classified as a Group 2A carcinogen, and its high heme-iron content can increase the risk of insulin resistance, which is detrimental to health.

While scientific evidence strongly supports the benefits of vegetarian diets, meaningful, community-driven action can be even more impactful. A good example is the 21-day health challenge launched by Tzu Chi volunteers. The program connects participants with restaurants, dieticians, and physicians, helping them personally experience the benefits of whole-food, plant-based eating. Ultimately, success in promoting vegetarian diets comes from personal commitment and active community participation. Dieticians and doctors can provide guidance, but the energy and dedication of grassroots involvement are the key to success.